In order for our eyes to see in both intense and low light conditions, molecular mechanisms allow for light and dark adaptation. The G-protein transducin is responsible for transducing signal from the photon receptor protein rhodopsin in rod and cone photoreceptors of our retina. Transducin is composed of three polypeptides, α, β and γ. The α subunit contains the GTP binding site. While waiting for a signal from rhodopsin, transducin is bound to the outer segment of the neuron. During exposure to normal daylight, transducin becomes displaced and migrates to another part of the cell: the photoreceptor is adapting to light. In darkness or very dim light, transducin will return to its “home” membrane.

Approximately 1,700 scientists visit SSRL annually to conduct experiments in broad disciplines including life sciences, materials, environmental science, and accelerator physics. Science highlights featured here and in our monthly newsletter, Headlines, increase the visibility of user science as well as the important contribution of SSRL in facilitating basic and applied scientific research. Many of these scientific highlights have been included in reports to funding agencies and have been picked up by other media. Users are strongly encouraged to contact us when exciting results are about to be published. We can work with users and the SLAC Office of Communication to develop the story and to communicate user research findings to a much broader audience. Visit SSRL Publications for a list of the hundreds of SSRL-related scientific papers published annually. Contact us to add your most recent publications to this collection.

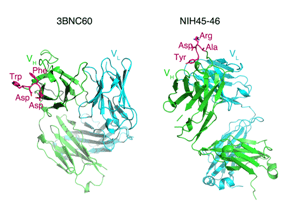

Strategies to combat HIV require structural knowledge of how antibodies recognize HIV envelope proteins and how they are used by the immune system to eliminate viruses and virally-infected cells. A few years after infection, some HIV-infected patients develop broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), which neutralize across many HIV strains and confer protection against simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in non-human primates when delivered by passive immunization (i.e. purified Abs were injected). Despite the fact that HIV-infected individuals can produce bNAbs, a vaccine that can elicit such Abs has yet to be identified or designed.

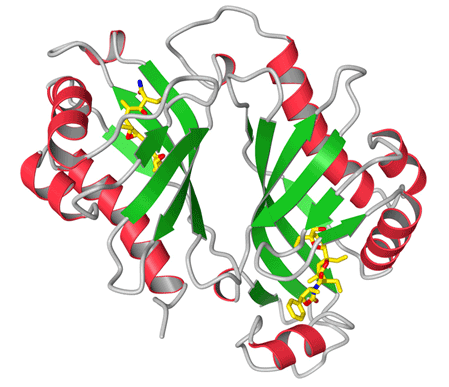

An enzyme is an efficient catalyst capable of accelerating a chemical reaction in an aqueous environment under mild conditions. It not only plays a vital role in sustaining life, but also provides a tool for living organisms to create complex chemical compounds, such as antibiotics and pheromones, that can improve the biological fitness of those organisms.

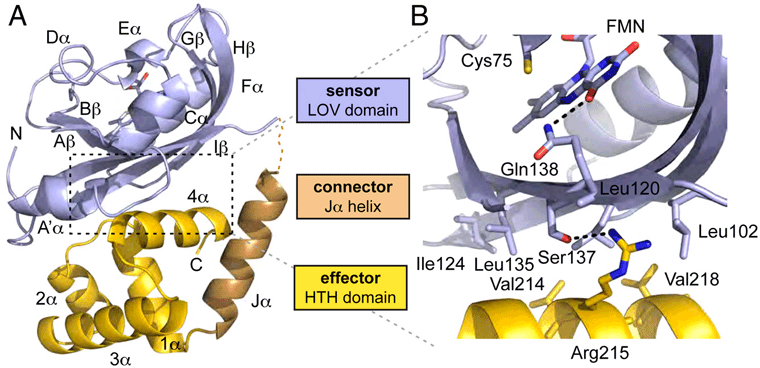

The ability of organisms to sense and respond to light availability is of great interest to those wishing to exploit these mechanisms in the areas of biotechnology and agriculture. A particular light sensing domain, termed the light-oxygen-voltage (LOV) domain, is found in plants, animals, and bacteria to control a wide variety of biological processes1-5. LOV domains oftentimes signal to a variety of attached effector domains including kinases, F-boxes, and DNA-binding domains. This leads to the questions: How does light stimulation of the LOV domain cause activation to such a wide variety of effector domains? And is there a shared mechanism? Understanding the molecular mechanism of how organisms use LOV domains might enable engineered light-induced control of pathways.

Materials that exhibit magnetism, superconductivity (the ability of electrons to travel without resistance across a material), and ferroelectricity (important for capacitors and used, for example, in medical ultrasound machines, infrared cameras and fire sensors) are the subject of significant scientific and technological research. These properties can depend strongly on the roughness of interfaces between layers as well as the thickness of these layers (often each a mere ~2.5 nanometers, or 1/16,000th the width of a human hair, thick); as such, the ability to characterize these layers at high-resolution is important. Yet few characterization techniques exist that have the ability to characterize the structure and uniformity of such complex structures.

By knowing the structures of proteins and their complexes with other molecules, biomedical scientists and biochemists can better understand how they work. This knowledge can lead to the design of new drugs and the engineering of faster enzymes for industrial applications, among many other applications. In x-ray crystallography, researchers send x-ray beams generated by a high-energy synchrotron like SSRL at protein crystals; the x-rays are diffracted from the periodic arrangement of protein molecules in the crystal, allowing the researchers to compute a three-dimensional electron density map of the protein molecule—which in turn allows for the mapping of individual atoms. The quality of the electron density map ultimately determines the accuracy of the atomic positions, and hence the overall quality of the protein structure.

Programmed cell death, or apoptosis, is a critical failsafe against uncontrolled proliferation. For this reason, apoptosis is frequently defective in cancer cells, allowing tumor growth to proceed unchecked. The inhibitor of apoptosis proteins, or IAPs, are some of the final “brakes” on apoptosis, directly inhibiting both caspases and their upstream activators (1,2,3,4). Thus it is unsurprising that IAP proteins are over-expressed in many human cancers (2,5).

A common problem in orthodontics is the narrowing of the space taken up by tissue connecting the root of a tooth to its bony socket ("periodontal ligament space") around teeth that are forced to change position with braces or other orthopedic fixation devices. Healthy periodontal ligament space is generally considered to be between 150 and 380 µm; yet as teeth are forced to move (and as patients age), this space can be narrowed too far, potentially causing a failure of the fibrous joint between the bone and tooth.

Organic semiconductors could usher in an era of foldable smart phones, better high-definition television screens and clothing made of materials that can harvest energy from the sun needed to charge your iPod or iPad, but there is one serious drawback: Organic semiconductors, while inexpensive, do not conduct electricity very well.

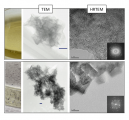

Manganese, one of the most abundant metals in soils and rocks, is important to the health of the environment: As it cycles between manganese-II and nanocrystalline manganese-III/IV oxides, it plays an important role in controlling the cycle and transport of soil nutrients and contaminants. Yet because the process is kinetically hindered, manganese will not oxidize rapidly in air; manganese needs a catalyst, often bacteria, to spur the process into action.