Microtubules (MTs) are hollow, nanometer-scale cylinders comprised of globular dimeric tubulin subunits that are involved in a variety of cellular functions, including intracellular trafficking and cell division. Tubulin subunits align end-to-end to form linear protofilaments that interact laterally in stabilizing the tubular wall. MTs occur in two types of populations: those undergoing dynamic instability (i.e. stochastic cycling between periods of MT growth and shrinkage) or more stable MTs in the axons and dendrites of post-mitotic mature neurons MTs. These two populations and other MT functionalities are controlled, in part, with the assistance of microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs).

Tau is a neuronal MAP known to regulate MT dynamic instability and MT bundling but is also implicated in neurodegenerative “tauopathies” (including Alzheimer’s and chronic traumatic encephalopathy in people suffering concussions). The structure-function relationship of Tau remains less well understood due, in part, to the intrinsically disordered nature of Tau. Thus, Tau structure is often described sequentially with an amino-terminal tail (N-terminal tail, consisting of a projection domain and proline-rich region), a microtubule-binding region, and a short carboxyl-terminal tail. Alternative splicing of exons 2/3 in the projection domain (PD) can result in short (-/-), medium (+/-), and long (+/+) N-terminal tails.

While previous in vivo studies had shown widely-spaced MT bundles in the axon initial segment (Tau is found in neuronal axons, leading to the possibility of a Tau-mediated MT-MT attractive potential), cell free experiments had concluded that Tau acts as a repulsive spacer between MTs. Researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara, KAIST (Korean Advanced Institute of Science and Technology), and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem performed small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) experiments at SSRL Beam Line 4-2 to uncover the conformation and MT-MT interactions mediated by Tau on MT surfaces and thereby reconcile many conflicting reports on the function of Tau.

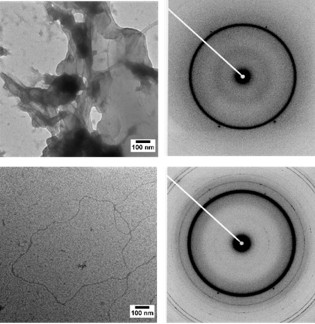

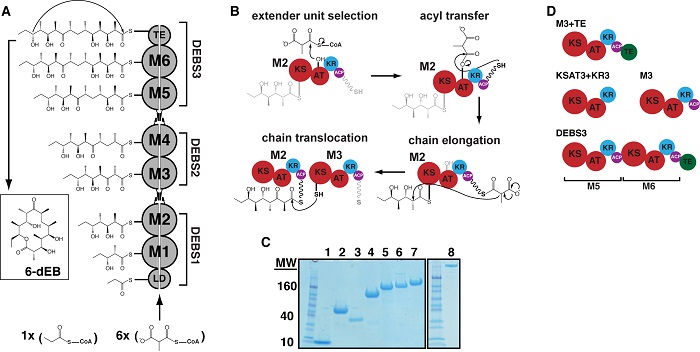

The research team investigated the in situ forces between Tau-coated paclitaxel-stabilized MTs that transitioned from nematically-oriented MTs (Fig. 1a) to bundled phases, the buckled rectangular phase (Fig. 1b) and the hexagonal phase (Fig. 1c) as a function of increasing applied osmotic pressure, mimicking the crowded environment of the cell [1]. In going from no coverage to high coverage of Tau isoforms, longer N-terminal tails sterically stabilized microtubules (preventing bundling up to 10,000 Pa in comparison to microtubule bundling at 1,000 Pa in absence of Tau, Fig. 1e). In striking contrast, coverage by Tau isoforms with the shortest N-terminal tails did not change the bundling pressure (1,000 Pa), even at higher coverages of 1:10 Tau-to-tubulin molar ratio (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. Long N-terminal tails of tau isoforms confer steric stabilization to microtubules (MTs). The sketches show (a) Oriented MTs (i.e. in the nematic phase) partially coated with Tau, (b) PEO-induced assembly of buckled MTs into the rectangular structure (labeled RBMT), and (c) Hexagonally assembled MT after unbuckling of MTs upon luminal entry of the chains at high PEO concentrations (labeled HBMT). PEO is colored yellow in (a) and (b). (d, e) Synchrotron SAXS data of mixtures of MTs with short 4RS (d) and long 4RL (e) tau isoforms (Φtau = 1/10, tau/tubulin dimer molar ratio) plotted as a function of increasing osmotic pressure induced by addition of increasing wt% of 20k PEO. For the short N-terminal isoform increasing PEO transitions the reaction mixture from nematic (NMT) to buckled rectangular packing (RBMT) and from RBMT to hexagonal (HMT) (d). In contrast, for the long N-terminal isoform, another mixture (Φ4RL=1/10) displays a transition directly from the NMT to the HMT bypassing the buckled RBMT phase. The suppression of bundling for 4RL to higher P (by more than an order of magnitude compared to 4RS) suggests that the isoform transitions from the “mushroom” to the “brush” conformation at Φ4RL = 1/10. The findings show that the long N-terminal tails confer steric stabilization and that Tau mushrooms are in a more extended state compared to predictions of classical polyelectrolyte theory (i.e. because the transition from mushroom to brush is occurring before the steric overlap between neighboring 4RL mushroom conformations). Adapted from [1].

This finding suggests that the longer N-terminal tails of Tau isoforms undergo a conformational transition from a mushroom to brush state in the higher coverage regime thus resisting bundling at higher pressures. Most significant is the finding that the brush state of Tau is crucial in preventing aggregation of microtubules, which otherwise would likely result in a loss of their ability to function as molecular rails in healthy neurons.

While Tau bound to MTs would seem to act as a repulsive spacer (especially Tau isoforms with longer N-terminal tails), the in vivo observation of widely-spaced MT bundles in the axon initial segment remained a mystery. In another study via optical microscopy, the researchers discovered that in preparing cell free reconstitutions in conditions mimicking physiology (without the MT-stabilizing agent paclitaxel but with the addition of GTP and maintained at 37˚ C), the addition of Tau would induce phase separation to areas of high and low MT density (indicating a Tau-mediated attractive potential between MTs) [2].

SAXS analysis revealed that these areas of high MT density had spacings similar to that of MT bundles found in the axon initial segment (Fig. 2a-g). Additionally, electron microscopy measurements not only confirmed these spacings but also revealed bundle geometries strikingly similar to the geometries found within the axon initial segment (Fig. 2h-j). The research team uncovered that this Tau-mediated interaction between MTs is a balance between the polymeric resistance to inter-digitation and biologically-encoded weak charge-charge attractions between Tau on opposing MTs. Previous cell free reconstitutions had not observed MT bundles due to the use of paclitaxel, a MT-stabilizing agent. Only through an aggregate of weak, Tau-mediated interactions along MTs of sufficient length will MT bundles manifest, a finding that was bolstered by a later study that showed that decreasing paclitaxel concentrations lead to longer MTs and Tau-induced MT bundles [3].

Figure 2. SAXS and TEM show that Tau-assembled MTs in active bundles at 37˚ C in 2 mM GTP recapitulate key in vivo features in neurons and other cells. a, Azimuthally-averaged SAXS data show that all six wild-type Tau isoforms induce MT bundles, with Bragg peak positions consistent with hexagonal lattices (top six profiles), as opposed to just microtubule form factor for no Tau (bottom profile). b-e, Line-shape analysis of SAXS data [resultant fits in red on (a)] yields the ensemble-averaged microtubule inner radius <rin> (b), hexagonal lattice parameter aH (c), wall-to-wall distance Dw-w (d), and Dw-w normalized by the calculated Tau projection domain radius of gyration, RGPD (e). f, g, Dw-w and Dw-w/RGPD as a function of Tau net charge (QTau) shows a monotonic decrease in Dw-w and a nearly constant Dw-w/RGPD ≈ 8-11, respectively. The latter is especially surprisingly, as the expected Dw-w/RGPD should be ~ 4. h, Electron microscopy of microtubules assembled with Tau (Φ3RM=1/20) at low magnification show distinct bundled domains, demonstrating phase separation. i, Domains of hexagonally-ordered arrays of microtubules (identified in white outlines, Φ3RL=1/20) with vacancies likely resulting from the suppressed (but still occurring) dynamic instability. j, Linear bundles of microtubules (Φ3RL=1/20), a result of extensive vacancy introduction and mimicking string-like microtubule bundles in the axon initial segment. In (i) and (j) the staining process exaggerates the microtubule wall thickness. Scale bars, 1 µm (h) and 500 nm [(i) and (j)]. Adapted from [2].

The intrinsic disorder of Tau on MTs allows for a fascinating blend of both biopolymer and protein characteristics; not only can the N-terminal tail of Tau transition to a polyelectrolyte brush on MT surfaces as a function of Tau isoform and coverage density, but attractions between charged amino acids on opposing N-terminal tails of Tau allow for complex MT bundle geometries.

Here, the researchers demonstrate the power of the SAXS-osmotic pressure technique in elucidating the distinct conformations of the protruding N-terminal tail of Tau (namely, the mushroom and brush state at low and high coverage, respectively), fundamentally altering the force between MTs. The paper reported the discovery that the brush conformation of Tau is crucial in preventing aggregation of microtubules, which otherwise would result in the loss of their function as molecular rails in healthy neurons.

They further reconcile conflicting in vivo and cell free studies by revealing that Tau does, in fact, induce MT bundles in dissipative physiological conditions (i.e. in the absence of the MT stabilizing agent paclitaxel and under GTP hydrolyzing conditions). The key insight is that only an aggregate of this weak, Tau-mediated interactions along long MTs (such as those found within the axon initial segment) will recapitulate microtubule bundles found in the axon. This unique interaction is contingent on the intrinsic disorder of Tau.

The functionalization of these protein nanotubes by Tau, a polyampholyte, is inherently absent in charged polymers containing all positive or all negative charges (e.g. like DNA, which only contains negative phosphate groups). These novel, emerging properties gives insight for the design of biologically-inspired materials with multiple interaction motifs of opposite charge.

Acknowledgements

Research primarily supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (BES) under award number DE-FG02-06ER46314 (self-assembly and force measurements in filamentous protein systems), the US National Science Foundation (NSF) under award number DMR-1401784 (protein phase behavior), and the US National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01-NS13560 and R01-NS35010 (tubulin purification and protein Tau isoform purification from plasmid preparations). U.R. acknowledges support from the Israel Science Foundation (Grant 351/08). M.C.C. was supported by NRF-2014R1A1A2A16055715, 2014M2B2A4030706 and APCTP. The x-ray diffraction work was carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the US DOE Office of Science by Stanford University. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program which supports BL4-2 is funded by the DOE Biological and Environmental Research and the NIH National Institute of General Medical Science (P41GM103393)