The determination of the crystallographic, electronic or magnetic structure of interfaces has remained one of the great challenges in all of materials science. The key reason is the difficulty to detect and isolate the weak interface signature from that of the dominant bulk. This is largely due to the lack of depth specificity of most techniques, impeding the detection of a signal from a well-defined depth, only. For lack of better capabilities scientists have tried to circumvent this problem, often studying the early stages of interface formation with surface science techniques or simply assuming "perfect" interfaces between "bulk" materials. Using advanced soft x-ray spectroscopy and microscopy techniques in conjunction with interface sensitive electron yield detection we are now able to look at buried interfaces and observe that, in reality, interfaces are quite different from model systems.

Modern magnetism is one area where interfaces play a crucial role. Today’s high-tech magnetic devices are based on thin film multilayers whose magnetic properties depend on the magnetic coupling and spin transport across interfaces. Examples are giant magnetoresistance structures, spin tunnel junctions, as well as "spintronics" devices based on spin injection. A specific interfacial problem which is of considerable scientific interest and technological importance is the origin of "exchange bias", an effect utilized in many of today's magnetic sensors and memory cells.

Modern magnetism is one area where interfaces play a crucial role. Today’s high-tech magnetic devices are based on thin film multilayers whose magnetic properties depend on the magnetic coupling and spin transport across interfaces. Examples are giant magnetoresistance structures, spin tunnel junctions, as well as "spintronics" devices based on spin injection. A specific interfacial problem which is of considerable scientific interest and technological importance is the origin of "exchange bias", an effect utilized in many of today's magnetic sensors and memory cells.

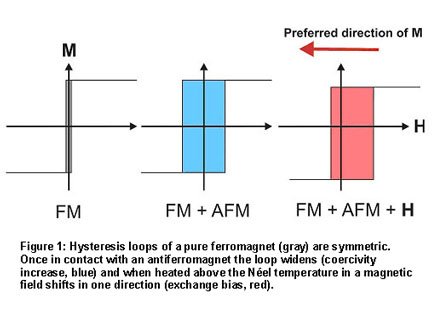

The exchange bias effect, empirically discovered nearly 50 years ago, is used today to create a well-defined ferromagnetic reference layer in a magnetic device. Natural ferromagnets have a preferred magnetization "easy axis", and an external field can align the spins into either of two equally stable directions along this axis - the magnetization loop is symmetric as shown in Fig. 1. When a ferromagnet (FM) is grown on an antiferromagnet (AFM) the exchange coupling between the two systems leads to an increased coercivity of the ferromagnet, which can be viewed as an increased "friction" to turn the spins around. The ferromagnetic hysteresis loop is still symmetric, indicating two equivalent easy directions. If, on the other hand, the AFM-FM system is grown in a magnetic field or, after growth, is annealed in a magnetic field to temperatures above the AFM Néel temperature, the hysteresis loop becomes asymmetric and is shifted from zero, as shown in Fig. 1. This unidirectional shift is called "exchange bias". There is now a preferred magnetization direction for the FM along which it is most easily aligned. The easy alignment direction can serve as a reference direction in a device. It is clear that exchange bias has to originate from the coupling of the spins in the AFM to those in the FM but, because of the magnetic neutrality of the AFM, the coupling has to involve uncompensated spins at the AFM-FM interface. The key to the exchange bias puzzle lies in the determination of the origin of these interfacial spins and their role in coercivity increases and bias.

It is the very difficulty associated with the determination of the magnetic interfacial structure mentioned above, that has impeded the solution of the exchange bias puzzle for more than forty years.

It is the very difficulty associated with the determination of the magnetic interfacial structure mentioned above, that has impeded the solution of the exchange bias puzzle for more than forty years.

Along come two powerful new magnetism techniques based on soft x-rays, the x-ray magnetic circular (XMCD) and linear (XMLD) dichroism techniques [1]. In conjunction with spectromicroscopy these x-ray techniques have allowed a unique fresh look at the old exchange bias problem and hold the promise to finally solving it. A series of XMCD/XMLD imaging experiments using the Photoemission Electron Microscope (PEEM2) at the ALS previously established the link of the AFM and FM domain structure, including the reorientation of the AFM spins in the vicinity of the interface[2,3]. The latest, just published [4,5], results home in on the all-important interface. They were obtained by two complementary experiments, high energy resolution (150 meV) soft x-ray absorption spectroscopy in total electron yield mode performed at Beam Line 10-1 at SSRL and high spatial resolution (50 nm) soft x-ray absorption microscopy using the PEEM2 microscope at the ALS.

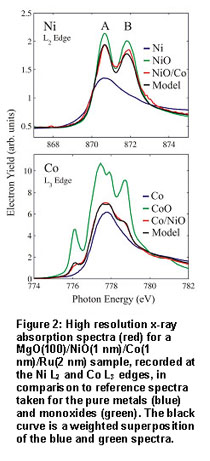

The SSRL spectroscopy results shown in Fig. 2 demonstrate that a thin Co layer deposited on top of bulk NiO (Co/NiO) contains Ni atoms that are in an environment somewhere between NiO and Ni metal, and Co atoms that are in an environment somewhere between Co metal and CoO. This is explained by an interfacial reaction in which the original NiO is reduced and the original Co is oxidized. A new interfacial layer is formed that we shall call NiCoOx.

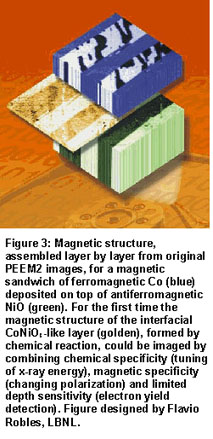

Magnetic images of the Co/NiO sandwich, obtained with the PEEM2 microscope at the ALS, are shown in Fig. 3. The Figure is an artist's rendition, with the original images put together layer by layer to illustrate the magnetic structures in the NiO and Co layers and the image of the NiCoOx. The antiferromagnetic NiO domain image (bottom: green) was obtained with XMLD spectromicroscopy, tuning the x-rays to the Ni L2 peaks in NiO (see Fig. 2 top). The ferromagnetic Co domain image (top: blue, white, black) was obtained with XMCD spectromicroscopy, tuning the x-ray energy to the Co metal L3 peak (see Fig. 2 bottom). The image of the domain structure of the NiCoOx interface layer (middle: golden, white, black) was obtained with XMCD spectromicroscopy, tuning the x-rays to the Ni L2 peak energy of 870.5eV (see Fig. 2 top). Since XMCD yields ferromagnetic contrast, the observed domain structure of the interface has to arise from uncompensated Ni spins formed by reduction of NiO. Close inspection reveals that the domains mimic the antiferromagnetic NiO domains below and the ferromagnetic Co domains above and therefore form the bridge between the two. The results indicate that the increase in coercivity and the bias shift in antiferromagnet/ferromagnet sandwiches, illustrated in Fig. 1, originate from the interfacial spins created by a chemical reaction. Further experiments show that in an external magnetic field most of the interfacial spins rotate with the ferromagnet, but they provide an increased rotational drag that leads to the widened magnetization loop. A small fraction of the interfacial spins that has not yet been isolated, is believed not to rotate at all in an external field because the spins are tightly coupled to the antiferromagnetic NiO lattice underneath. These spins are believed to give rise to the exchange bias phenomenon illustrated in Fig. 1. Because of their small abundance, corresponding to a fraction of a monolayer, only, the isolation of their magnetic signal and the determination of their spatial location remain a great challenge for future experiments.

Magnetic images of the Co/NiO sandwich, obtained with the PEEM2 microscope at the ALS, are shown in Fig. 3. The Figure is an artist's rendition, with the original images put together layer by layer to illustrate the magnetic structures in the NiO and Co layers and the image of the NiCoOx. The antiferromagnetic NiO domain image (bottom: green) was obtained with XMLD spectromicroscopy, tuning the x-rays to the Ni L2 peaks in NiO (see Fig. 2 top). The ferromagnetic Co domain image (top: blue, white, black) was obtained with XMCD spectromicroscopy, tuning the x-ray energy to the Co metal L3 peak (see Fig. 2 bottom). The image of the domain structure of the NiCoOx interface layer (middle: golden, white, black) was obtained with XMCD spectromicroscopy, tuning the x-rays to the Ni L2 peak energy of 870.5eV (see Fig. 2 top). Since XMCD yields ferromagnetic contrast, the observed domain structure of the interface has to arise from uncompensated Ni spins formed by reduction of NiO. Close inspection reveals that the domains mimic the antiferromagnetic NiO domains below and the ferromagnetic Co domains above and therefore form the bridge between the two. The results indicate that the increase in coercivity and the bias shift in antiferromagnet/ferromagnet sandwiches, illustrated in Fig. 1, originate from the interfacial spins created by a chemical reaction. Further experiments show that in an external magnetic field most of the interfacial spins rotate with the ferromagnet, but they provide an increased rotational drag that leads to the widened magnetization loop. A small fraction of the interfacial spins that has not yet been isolated, is believed not to rotate at all in an external field because the spins are tightly coupled to the antiferromagnetic NiO lattice underneath. These spins are believed to give rise to the exchange bias phenomenon illustrated in Fig. 1. Because of their small abundance, corresponding to a fraction of a monolayer, only, the isolation of their magnetic signal and the determination of their spatial location remain a great challenge for future experiments.

References

- For more information see http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/stohr/index.htm

- F. Nolting, A. Scholl, J. Stöhr, J. W. Seo, J. Fompeyrine, H. Siegwart, J.-P. Locquet, S. Anders, J. Lüning, E. E. Fullerton, M. F. Toney, M. R. Scheinfein, and H. A. Padmore, Direct Observation of the Alignment of Ferromagnetic Spins by Antiferromagnetic Spins,Nature 405, 767 (2000)

- H. Ohldag, A. Scholl, F. Nolting, S. Anders, F.U. Hillebrecht, and J. Stöhr, Spin Reorientation at the Antiferromagnetic NiO(001), Surface in Response to an Adjacent Ferromagnet, Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 247201 (2001)

- T. J. Regan, H. Ohldag, C. Stamm, F. Nolting, J. Lüning, J. Stöhr and R. L. White, Chemical effects at metal/oxide interfaces studied by x-ray-absorption spectroscopy, Phys. Rev. B 64, 214422 (2001).

- H. Ohldag, T. J. Regan, J. Stöhr, A. Scholl, F. Nolting, J. Lüning, C. Stamm, S. Anders and R. L. White, Spectroscopic identification and direct imaging of interfacial magnetic spins,Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 247201 (2001).

H. Ohldag, T. J. Regan, J. Stöhr, A. Scholl, F. Nolting, J. Lüning, C. Stamm, S. Anders and R. L. White, Spectroscopic identification and direct imaging of interfacial magnetic spins,Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 247201 (2001).