Modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) are assembly line enzymes that synthesize a wide variety of medicinally important polyketide natural products such as erythromycin (antibiotic), rapamycin (immunosuppressant), and epothilone (chemotherapeutic). Type I modular polyketide synthases synthesize polyketide natural products by performing successive decarboxylative condensation and optional β-keto group reduction reactions1,2. Modular PKS are dimeric multidomain proteins and consist of one or more catalytic “modules”. In general, a module minimally contains three functional domains, ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP), all of which are required to perform polyketide chain extension. PKSs may also contain one or more non-condensing domains such as ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoylreductase (ER), which catalyze modification of the β-keto group formed during chain extension. During polyketide biosynthesis, the growing acyl chain is carried by the ACP and moves from one catalytic domain to another, where each domain performs a specific chemical task. Once all of the domains in a PKS module have processed the polyketide substrate, the extended and modified polyketide chain is transferred to the next PKS module in the pathway for further processing. The last PKS module in the pathway typically contains a thioesterase (TE) domain which catalyzes the release of the fully extended polyketide chain from the PKS.

Lasalocid A is an important veterinary antibiotic. In lasalocid A biosynthesis, seven modular PKS proteins (Lsd11 to Lsd17) work together to construct the dodecaketide backbone from five malonate, four methylmalonate, and three ethylmalonate building blocks3. Next, an epoxidase, Lsd18, converts the two E-olefins in the polyketide backbone into epoxides, and finally, an epoxide hydrolase, Lsd19, catalyzes two consecutive epoxide-opening cyclization reactions to give the final product lasalocid A4–6.

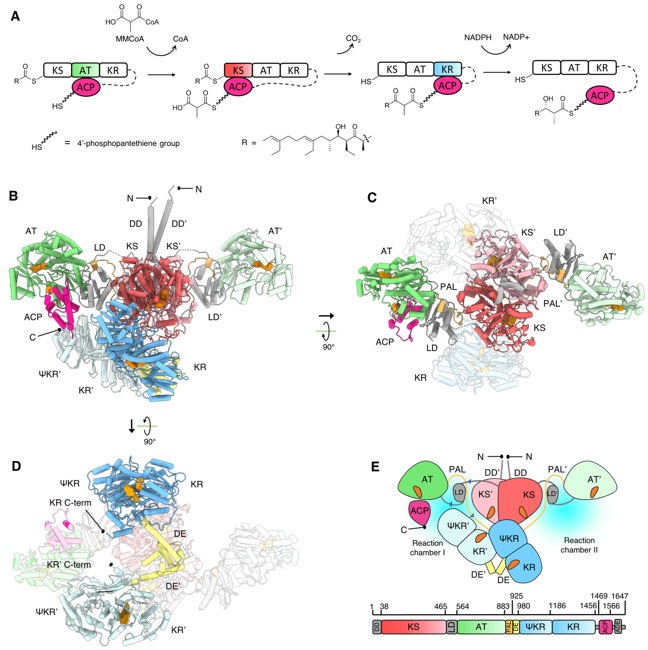

While the low-resolution small-angle x-ray scattering derived models and medium-resolution cryo-electron microscopy reconstructions of modular PKS have been reported7–10, a high-resolution structure of an intact PKS module remained elusive for over 30 years since their discovery. Recently, research led by Chu-Young Kim, professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Texas at El Paso and Saket R. Bagde, Ph. D. candidate at Cornell University, in collaboration with SSRL scientist Irimpan Mathews, and Christopher Fromme, Associate Professor at Cornell University, revealed the first high-resolution structures of an intact modular PKS, Lsd1411. The team used x-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy to catch the PKS module in two distinct catalytic states. These structures reveal a wealth of information on the architecture and interdomain interactions of Lsd14 (Fig. 1).

The team used multiple beamlines at SSRL including 7-1, 9-2, 12-2, and 14-1 for screening and data collection of over 200 crystals of Lsd14, over a period of 3 years. Finally, diffraction data sets collected at SSRL BL9-2 were used to obtain the 2.4 Å resolution crystal structure of Lds14 stalled at the transacylation state. Seven of the eight functional domains that constitute the Lsd14 homodimer were clearly visible in the electron density map and could be modelled, providing an unprecedented amount of detailed information on modular PKS architecture. Surprisingly, these domains are arranged asymmetrically in the Lsd14 structure, suggesting that the two reaction chambers operate asynchronously. In the crystal structure, the ACP domain is docked on the AT domain forming specific interactions that are required for the transacylation reaction.

Next, the team used cryo-electron microscopy to determine the 3.1 Å resolution structure of Lsd14 trapped in the condensation step of PKS reaction cycle. In this structure, the ACP domain is docked to the KS domain, which is required for the condensation reaction to occur.

Overall, this study provides a high-resolution blueprint of interdomain interactions within a modular PKS in two distinct catalytic states (Fig. 1). This information will be useful for future studies aimed at engineering of modular PKSs to produce polyketide product analogs.

- J. Cortes, S. F. Haydock, G. A. Roberts, D. J. Bevitt and P. F. Leadlay, "An Unusually Large Multifunctional Polypeptide in the Erythromycin-producing Polyketide Synthase of Saccharopolyspora erythraea", Nature 348, 176–178 (1990).

- S. Donadio, M. J. Staver, J. B. McAlpine, S. J. Swanson and L. Katz, "Modular Organization of Genes Required for Complex Polyketide Biosynthesis", Science 252, 675 LP – 679 (1991).

- A. Migita et al., "Identification of a Gene Cluster of Polyether Antibiotic Lasalocid from Streptomyces lasaliensis", Biosci, Biotech. Biochem. 73, 169–76 (2009).

- A. Minami et al., "Sequential Enzymatic Epoxidation Involved in Polyether Lasalocid Biosynthesis", J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7246–9 (2012).

- K. Hotta et al., "Enzymatic Catalysis of Anti-Baldwin Ring Closure in Polyether Biosynthesis", Nature 483, 355 (2012).

- F. T. Wong et al., "Epoxide Hydrolase-lasalocid a Structure Provides Mechanistic Insight into Polyether Natural Product Biosynthesis", J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 86–9 (2015).

- S. Dutta et al., "Structure of a Modular Polyketide Synthase", Nature 510, 512–517 (2014).

- A. L. Edwards, T. Matsui, T. M. Weiss, and C. Khosla, "Architectures of Whole-Module and Bimodular Proteins from the 6-Deoxyerythronolide B Synthase", J. Mol. Biol. 426, 2229–2245 (2014).

- J. R. Whicher et al., "Structural Rearrangements of a Polyketide Synthase Module during Its Catalytic Cycle", Nature 510, 560–564 (2014).

- X. Li et al., "Structure–Function Analysis of the Extended Conformation of a Polyketide Synthase Module", J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6518–6521 (2018).

S. R. Bagde, I. I. Mathews, C. Fromme and C.-Y. Kim, "Modular Polyketide Synthase Contains Two Reaction Chambers that Operate Asynchronously", Science 374, 723 (2021) doi: 10.1126/science.abi8532