Manganese(IV) oxides are powerful scavengers of toxins and trace metals, but they are also strong oxidants in the environment (1). Certain common microbes can also ‘breathe’ manganese oxides, in a process known as anaerobic respiration (2). During these environmental –commonly with sulfur or iron species– and biological interactions, manganese oxides are often dissolved. But what happens to the manganese next? Manganese could be ‘fixed’ into secondary minerals, or stay reduced and soluble and be available to easily re-oxidize.

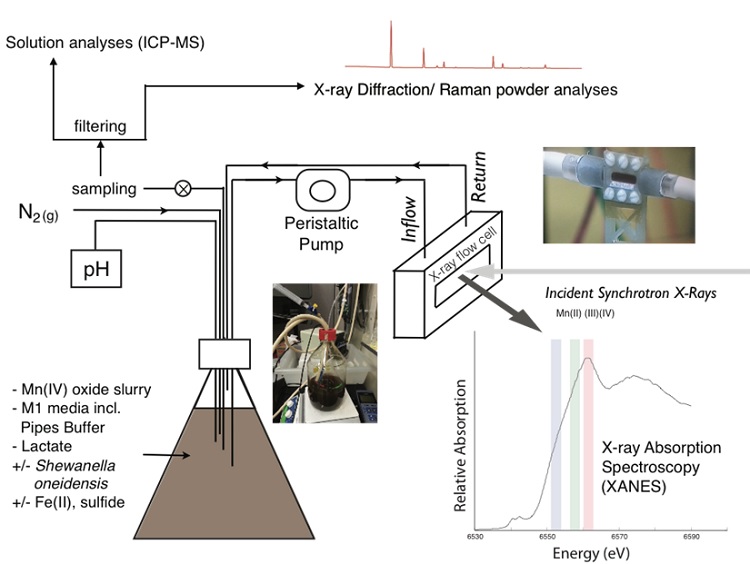

A collaborative team, including geobiologists from the California Institute of Technology, microbiologists from the University of Southern California, and beam line scientists at SSRL investigated what happens to manganese(IV) oxides during environmentally-common reduction pathways like ferrous iron- and sulfide- driven reactions as well as the anaerobic respiration of manganese oxides by a common metal-reducing microbe, Shewanella oneidensis. The team set up a flow-through system to probe these reaction sequences using real-time x-ray spectroscopic measurements. The reactions occurred in a large reaction vessel where anaerobic tubing pumped a small portion of the reacting fluid to a flow cell where the manganese redox and mineralogical state was measured by the x-ray beam continuously (Figure 1). Precipitate samples were also retrieved throughout the experiments to analyze with complimentary techniques including x-ray diffraction and Raman spectroscopy. These combined real-time measurements showed the evolution from manganese(IV) oxides to a variety of secondary manganese phases.

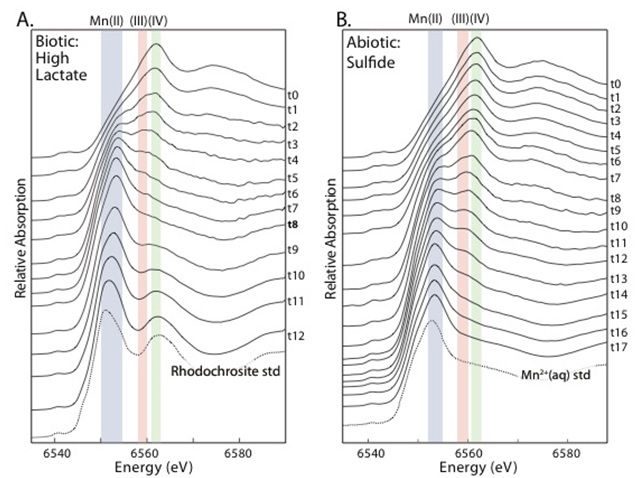

Three major solid phases were formed in the various experimental conditions, reflecting contributions from the reductive processes and the solution conditions. During the microbial respiration of manganese oxides by Shewanella oneidensis, a transient Mn(III) oxyhydroxide phase was observed before all the manganese was reduced and a majority of it was mineralized as a Mn-carbonate (rhodochrosite), because the microbial respiration led to the oxidation of lactate into inorganic carbon (like CO2) (see Figure 2A). By limiting the amount of organic carbon available to the microbes, the Mn(III) oxyhydroxide phase was able to be stabilized in the reaction vessel system. However, under high-phosphate conditions, no Mn(III) phase was observed and instead the microbial reduction sequence proceeded directly from Mn(IV) oxides to a Mn(II)-phosphate solid. In contrast, when manganese oxides were reduced by adding ferrous iron or sulfide aliquots to the reaction vessel, a Mn(III) oxyhydroxide phase was again observed but no solid Mn(II) phase formed (see Figure 2B). Like the biological experiments, the Mn(III) phase could be stabilized by limiting the reductant added. But because these abiotic reactions only involved manganese and iron or sulfide, they didn’t oxidize lactate and no inorganic carbon was produced, so carbonate precipitation was not promoted. pH measurements indicated, however, that the sulfide-induced reduction of manganese oxides in particular could promote Mn-carbonate precipitation in environments with sufficient inorganic carbon (like seawater). The alkalinity production, inorganic carbon and phosphate availability were direct controls on the production of secondary minerals like Mn(II)-carbonates and Mn(II)-phosphates, while the Mn(III) oxyhydroxide appeared to be more related to the availability of aqueous (reduced) manganese and the balance of electron donors (like ferrous iron, sulfide, and organic carbon) and electron acceptors (manganese oxides).

These experimental insights are important in understanding the reactivity and sequestration of manganese in modern environments; but also, from a geological perspective, understanding the environmental and biological influences on mineral precipitation is critical to interpreting the rock record. The reactions monitored in this study now constrain how various manganese minerals –including Mn(II)-carbonates and Mn(III) phases– deposited hundreds of millions and even billions of years ago might be deciphered to illuminate ancient environmental conditions.

- B. M. Tebo, H. A. Johnson, J. K. McCarthy and A. S. Templeton, “Geomicrobiology of Manganese(II) Oxidation”, Trends Microbiol. 13, 9 (2005).

- C. R. Myers, and K. H. Nealson, “Bacterial Manganese Reduction and Growth with Manganese Oxide as the Sole Electron Acceptor”, Science 240, 4857 (1988).

J. E. Johnson, P. Savalia, R. Davis, B. D. Kocar, S. M. Webb, K. H. Nealson and W. W. Fischer, "Real-time Manganese Phase Dynamics during Biological and Abiotic Manganese Oxide Reduction", Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 8 (2016), DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b04834.