Spintronics is a field that keeps both scientists and engineers excited from a fundamental physics and applications perspective. But what is “spintronics” exactly? In order to understand this new field of magnetism research, it is necessary to take a step back and revisit conventional electronics. For almost a century, electronic devices - starting with the early vacuum tubes – have used the charge of electrons to store and process information. For example, a modern computer chip has millions of transistors and capacitors in which electronic charge is stored, processed and transferred from one element to the other. There are two major challenges regarding this approach. Firstly, while each capacitor only holds a very small charge, it quickly adds up over the entire chip because of the large number of elements. Secondly, because of the small dimensions of the electric conductors a lot of heat is produced during operation. Furthermore, the ever-shrinking dimensions of memory cells can cause these elements to “leak” charge and become unstable. Spintronics is a relatively new field with a potential to address these challenges. The essential idea of spintronics is to not only use the charge of an electron to encode information but to also use the spin of electron. Every electron exhibits this intrinsic quantum mechanical property with its spin either being “up” or “down”. Such an up or down magnetic spin can store information permanently and does not require supporting electronics to keep it stable. In spintronics, binary information therefore does not correspond to the presence (1) or absence (0) of charge, but to the fact whether the spin of a small magnetic element is up or down. In addition, by generating pure spin currents it is possible to transport spin without moving the corresponding electric charge. This allows for transfer of information from one cell to the other using much less energy, as essentially no heat is generated, ultimately making spintronic devices more energy efficient. Evidently, to generate and manipulate spin currents in such nanoscale devices, it is important to observe how electronic spins are affected during spin transport. An atomic level of understanding from generation of spin currents (ferromagnet) to the spin transport from a ferromagnet to non-magnet is very crucial. However, directly observing these spin currents is extremely challenging due to magnetic moment injected into nonmagnet being really small, less than 1/10000 of a regular ferromagnet!

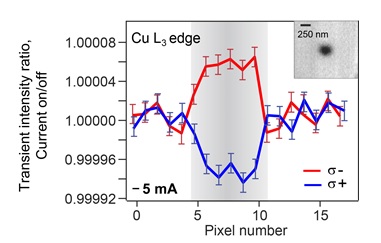

The aim of this experiment was to tackle this challenge and observe how spins travel from a ferromagnet to a non-magnet. For this purpose a nanopillar sample with diameter of 250 nm was used to inject a spin-polarized current from a ferromagnet (cobalt) into a non-magnet (copper) and imaged with a scanning transmission x-ray microscope (STXM) at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL). STXM microscopy technique provides the necessary spatial resolution to image nanoscale devices and also enables magnetic properties to be measured in an element specific manner. What that means is that STXM allows for the researchers to focus on the magnetic properties of the non-magnet Cu only, without being distracted by the much larger magnetic moment in the adjacent Co layer. As a next step, to be able to detect an extremely small induced magnetic moment in Cu, the research team developed an advanced ‘lock-in’ detection scheme, where they synchronized the current applied to the sample with the frequency of the probing x-ray pulses from the SSRL synchrotron. This detection scheme allowed the researchers to increase the sensitivity and stability of the magnetic x-ray microscopy to unprecedented levels, providing the ability to detect magnetic moments 100,000 times smaller than a normal ferromagnet, i.e. Co. In other words, this technique allowed them to find a magnetic needle consisting of only magnetic atoms hidden in a haystack that is the bulk of non-magnetic material. But even more it finally allowed them to detect the small magnetic moment induced in Cu when they passed a current from an adjacent Co layer. This is demonstrated in figure 1, where the miniscule change in absorption of circularly polarized x-rays – so called dichroism - across a Cu contact is shown when an electric current is applied. Upon switching the helicity of the polarized x-rays the dichroism reverses its sign as well which indicates that the change is caused by a magnetic moment in the Cu.

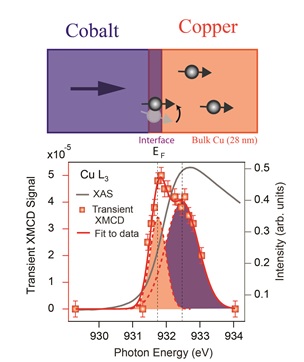

The next step was to carefully record the dependence of the magnetic signal on the energy of the x-rays, which led to a quite surprising finding. The researchers observed a large change in the magnetic moment per atom right at the interface, while a much smaller change in atomic magnetization was observed throughout the entire bulk of the Cu layer. This was possible due to the fact that the magnetic states at the interface appear at slightly different x-ray energy than in the bulk (Figure 1b). Looking at the Co/Cu interface first, the magnetic moments of the Cu atoms at the interface are aligned by the Co moments across the interface even prior to the applied current, so the first few atomic layers in the Cu essentially behave like a ferromagnet. However, this coupling is not perfect since the Cu atoms resist the ferromagnetic order. Hence, when the spin polarized electrons, i.e. spin currents, reach the Co/Cu interface, they increase the alignment of the interfacial Cu atoms, leading to the second peak at higher energy (purple) in the magnetic response shown in figure 2. The current then enters the bulk of Cu and induces a magnetic moment leading to the first peak (orange). Another striking conclusion is that the injected current “wastes” a significant portion of its moment already at the interface, and only a certain fraction makes it through the bulk of the Cu. These results clearly show that it is necessary to carefully decouple the source of the spin current (ferromagnet) and the material that transport the spins to achieve high efficiency spin transport.

R. Kukreja, S. Bonetti, Z. Chen, D. Backes, Y. Acremann, J. A. Katine, A. D. Kent, H. A. Dürr, H. Ohldag and J. Stöhr, "X-ray Detection of Transient Magnetic Moments Induced by a Spin Current in Cu", Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 096601 (2015), DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.096601.