In solids, the Fermi surface is the boundary between occupied and unoccupied electron levels, just as the shoreline of the ocean is the boundary between water-filled and dry regions Earth. And, just like a shoreline surrounding a body of water, every Fermi surface should form a single unbroken loop. Consequently, the 1998 discovery of disconnected segments of the Fermi surface in cuprate superconductors – Fermi arcs – shocked and perplexed physicists, just as finding the edge of the world would shock a sailor today[1].

Recent attempts to resolve this conundrum focused on finding the “back side” of a Fermi arc, based on the belief that matrix elements, which govern the photo-emission process, hid it in a fog. Consequently, great excitement was generated when Meng, et al.[2] reported that they had found just the right conditions to pierce that fog and observe the back side. However, shortly afterwards, King, et al. [3] reported that the observation of Meng, et al. was a mirage; specifically, a reflection of the Fermi arc itself caused by the superstructure of the underlying lattice. In any event, all models predicting the formation of a small pocket to connect the ends of a Fermi arc have difficulty explaining the temperature dependence of the arc, which grows smoothly above TC.[4]

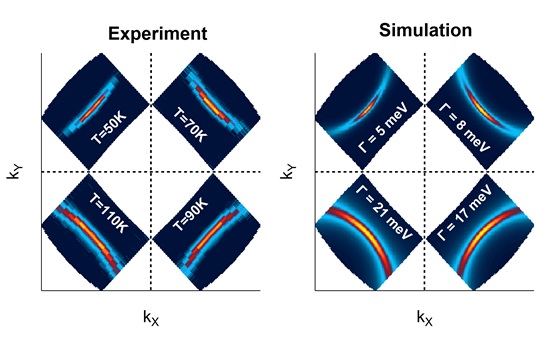

In a study recently published in Nature Physics, researcher Ted Reber, along with co-workers in Prof. Dan Dessau’s group at the University of Colorado, performed angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) at SSRL Beam Line 5-4 to determine the origin of Fermi arcs in the cuprates. The ability of ARPES to directly image the momentum states of electrons in a solid make it the ideal tool to study Fermi arcs, and the team’s work would not have been possible without the low-energy photons and excellent experimental resolution of Beam Line 5-4 at SSRL. The low photon energy enabled the team to isolate a single band from complicating features, such as the afore-mentioned superstructure, the incoherent background, the shadow bands, and so on. The beamline’s excellent energy resolution afforded the ability to resolve the superconducting gap, even very close to the node (<2°). To analyze the resulting spectrum, they used a new technique which called for the unorthodox step of integrating the ARPES spectrum along momentum to extract a spectral weight for the band. After normalizing to a reference Fermi edge they had a measure of the density of states for a single slice through the band structure. As tomography is the process of imaging a volume via individual slices, this technique determines what is called the tomographic density of states (TDoS). For quantitative analysis, the TDoS was fit to a conventional Dynes formula for the density of states for s-wave superconductors[5]. Even though the d-wave gap is momentum-dependent in the cuprates, for each slice the gap is effectively single-valued, so Dynes’s original form holds. This fit returns two parameters: the superconducting gap magnitude, Δ, and the pair-breaking rate, Γ.

With this analysis technique, they determined the following two facts. First, Δ changes very little with temperature, even through TC, suggesting Cooper pairs continue to exist in the normal state. Second, Γ is unconventionally large and strongly temperature-dependent, shifting weight from the peaks into the gap and effectively filling it. The constancy of Δ indicates that even in the normal state the band is still bent back and does not cross the Fermi energy. Instead it lurks just below the surface like a reef. Consequently, the Fermi arc is not a true Fermi surface and need not form a complete loop. The large and temperature-dependent Γ shifts real weight from the gap edge to the Fermi energy, forming the Fermi arc. Consequently, the arc is a byproduct of the intense competition between pair-forming and pair-breaking processes, just like a storm causes waves to crash on a reef, creating the froth and foam that gives the illusion of a coastline. Far from inconsequential, this foam of non-quasiparticle states is a fascinating candidate to explain the non-Fermi liquid physics that dominates the normal state of the cuprates.

[1] Norman, M. et al. Destruction of the Fermi surface in underdoped high-TC superconductors. Nature 392, 157(1998)

[2] Meng, J. et al. Coexistence of Fermi arcs and Fermi pockets in a high-Tc copper oxide superconductor. Nature (London) 462, 335 (2009)

[3] King, P.D.C. et al, Structural origin of apparent Fermi surface pockets in angle-resolved photoemission of Bi2Sr2-xLaxCuO6+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 127005 (2011).

[4] Kanigel, A. et al. Evolution of the pseudogap from Fermi arcs to the nodal liquid. Nature Physics 2, 447 (2006).

[5] Dynes, R. C., Narayanamurti, V., Garno, J.P., Direct Measurement of Quasiparticle-Lifetime Broadening in a Strong-Coupled Superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 41,1509-1512 (1978)

Reber, T. J. et al. The Origin and Non-quasiparticle Nature of Fermi Arcs in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Nature Physics 8, 606-610 (2012) doi:10.1038/nphys2352