Brain injuries from stroke are both common and costly. The NIH has estimated that the total annual cost of stroke in the United States is $43 billion including direct medical care and the costs related to lost productivity. It has been recognized that rapid diagnosis and treatment is essential to limit neuronal cell death from either a bleed into the brain (hemorrhagic stroke) or a blockage that deprives part of the brain of oxygen (ischemic stroke). The Synchrotron Medical Imaging Team, a group of Canadian, US, and European scientists from diverse backgrounds are collaborating to better understand the underlying chemistry of stroke and how to best image and treat stroke patients.

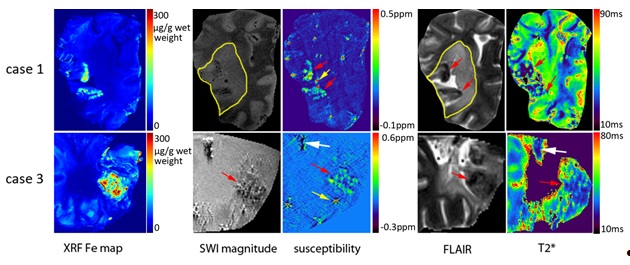

Clinical imaging of the brain is a major tool used for both the diagnosis and follow up of stroke patients. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and in particular susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) can visualize the excess iron associated with small hemorrhages. Weili Zheng, Sam Webb, Mark Haacke and Helen Nichol have examined various MRI imaging modalities for their ability to quantitatively image iron and calcium in brains from people who died of stroke (Zheng et al. 2012, in press). Using SSRL’s XRF rapid scanning Beam Line 10-2 in parallel with MRI at Wayne State University they were able to map and quantify iron and calcium using XRF and MRI on the same slices of human brain to show which MR sequences could best distinguish stroke features (Fig. 1). They found that susceptibility maps were superior for imaging iron where bleeding or necrosis had occurred while T2* mapping was better at visualizing the changes related to ischemic stroke.

The brain cells (neurons) not immediately killed by a stroke often die in the following days and weeks. These cells might be saved if we understood the cascade of chemical reactions that lead to their death. Following a hemorrhagic stroke, the blood cells that flood into the brain tissue can release iron from the breakdown of hemoglobin. Using SSRL’s XRF imaging Beam Lines 2-3 and 10-2, Dr. Fred Colbourne is examining the possible role of iron in disrupting the delicate chemical balance that keeps brain cells alive. Other methods had shown that iron is elevated in the affected hemisphere of the brain but XRF imaging showed that this iron is well contained in the peri-hematoma region. Iron chelators have been suggested as a stroke therapy for humans. Using quantitative XRF mapping Dr. Colbourne found that while a ferric iron chelator did reduce brain iron levels it did not improve the stroke-related disabilities in the rats (Auriat et al. 2012).

Ischemic stroke, caused by a clot or a narrowing that prevents the flow of blood through a vessel also disturbs normal brain chemistry, but in different ways. It is known that specific neurons in the brain are susceptible to ischemia, but the chemistry behind this vulnerability is unknown. Mark Hackett, a postdoctoral fellow in the team, working with Phyllis Paterson, Graham George and Ingrid Pickering is integrating XRF mapping and sulfur K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) with traditional biochemical and histological methods. This approach has now been used to gain a greater understanding of the total neurochemical “picture” of ischemic stroke, and underlying biochemical pathways through which stroke therapies minimise brain damage. Using Beam Lines 10-2 and 2-3, the distribution of Zn, and ions such as K, Cl, and Ca was determined in the healthy rat brain and at various time points after ischemic stroke, and after prolonged but gentle brain cooling (hypothermia), a promising stroke therapy (Silasi et al. 2012).

In addition to studying the distribution of metals and ions at Beam Line 10-2 and 2-3, the speciation of sulfur within the brain can be determined at Beam Line 4-3. Recent work by Mark Hackett has demonstrated that taurine (an abundant amino acid for which the neurological role remains unknown) levels within specific brain regions correlate to the density of neurons (Hackett et al. 2012). However, this trend is only observed when flash frozen unfixed brain tissue is analysed, highlighting that sample preparation is a crucial aspect for studying chemical speciation and distribution within the brain. Future work at BL 4-3 will focus on identifying alterations in the distribution of taurine, as well as other sulfur species (i.e., thiols and disulfides) as a consequence of ischemic stroke.

Using SSRL’s soft and hard x-ray facilities as well as the Canadian Light Source, the Synchrotron Medical Imaging Team is answering key questions that impact the health and recovery of stroke patients and their families.

Gergely Silasi, Ana C Klahr, Mark J Hackett, Angela M Auriat, Helen Nichol and Frederick Colbourne. Prolonged therapeutic hypothermia does not adversely impact neuroplasticity after global ischemia in rats. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism (2012), 1–10

Angela Auriat, PhD; Gergely Silasi, PhD; Zhouping Wei, PhD; Rosalie Paquette, BSc; Phyllis Paterson, PhD; Helen Nichol, PhD, Frederick Colbourne. Ferric iron chelation lowers brain iron levels after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats but does not improve outcome. Experimental Neurology 234 (2012), 136–143

Mark J. Hackett,† Shari E. Smith,‡ Phyllis G. Paterson,‡ Helen Nichol,§ Ingrid J. Pickering,† and Graham N. George*,† X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy at the Sulfur K-Edge: A New Tool to Investigate the Biochemical Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration. ACS Chem. Neurosci. (2012), 3, 178−185

W. Zheng, E. M. Haacke, S. M. Webb and H. Nichol, "Imaging of Stroke: A Comparison between X-ray Fluorescence and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods", Magn. Reson. Imaging (published online, July 11, 2012) doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.04.011