Beam Line 4-3 at SSRL opened its doors to researchers in March 2009. It replaced 54-pole wiggler Beam Line 6-2, which carried out yeoman’s work for many years at SSRL. The 20-pole wiggler of Beam Line 4-3 produces high-resolution x-ray spectra in the 2.4-14 keV energy range that makes Beam Line 4-3 especially useful to study the elements sulfur, chlorine, and calcium, which are important to biology, geology and archaeology.

Science is the search for the unexpected, and Beam Line 4-3 is a great facilitator. Its special capabilities have been turned to the study of sulfur in archaeological treasures. For example, several major museums around the world exhibit the restored and preserved wrecks of wooden ships that were raised up from what was their watery grave.

During their years of submergence, the sunken ships were colonized by anaerobic marine bacteria and their activities permeated sulfur throughout the wood. Some wooden planks became 8 percent sulfur by weight. The sulfur preserved the wood from degradation in the ocean, but became a source of concern in the museums. The reason is that, once exposed to air, the sulfur slowly converted to sulfuric acid and the sulfuric acid attacked the wood. This process has become a major threat to the 17th century Swedish warship Vasa, on exhibit at the Vasamuseet, Stockholm.

The story continues. In 2010, the bronze military ram from a Roman warship was recovered off the coast of Sicily, near Acqualadrone (‘Sea of Thieves’). The ram was a prow-mounted offensive weapon used during battle to sink enemy ships. Its discovery was especially unique because the wooden strutwork supporting the ram was still intact and in place. 14C dated the wood to 287 BCE, placing the ram and its ship in the earliest naval battles of the First Punic War. Elemental analysis showed that the wood was impregnated with traces of iron, copper, and zinc – and 4 percent sulfur.

Enter Beam Line 4-3. Francesco Caruso and Eugenio Caponetti from the University of Palermo contacted SSRL scientist Patrick Frank to see if x-ray spectroscopy could help. He and Dr. Ritimukta Sarangi, also of SSRL, used the high flux and resolution of Beam Line 4-3 to measure excellent but very complex x-ray spectra of sulfur inside two samples of wood from the strut of the Roman ram. Dr. Frank then used his library of sulfur x-ray spectra to match the spectrum from the wood.

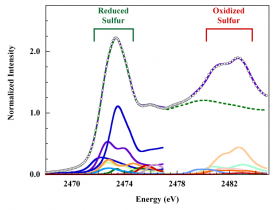

The points in the Figure below represent the x-ray spectrum of sulfur in wood from the ancient Roman ram. The many spectra underneath represent the welter of molecules needed to reproduce the complexity of sulfur in the wood. They add up to give the purple line going through the points. The dashed green line is the contribution made to the spectrum by reduced sulfur alone. This work has recently been published in Analytical Chemistry.

We now have a good idea of the kinds of sulfur that preserved the wood beneath the sea for 2300 years. But this sulfur is a nascent threat today. The next step is to protect this magnificent historical artifact by preventing the sulfur from changing into sulfuric acid.

Beam Line 4-3 has been active in other rescue missions. The Mary Rose was the flagship of Henry VIII’s navy, but sank outside of Portsmouth in 1545 while maneuvering to engage the French fleet. After 437 years, she was raised in 1982 and now suffers from the same ‘sulfur problem’ as the Vasa. Due to the years spent under the seabed, the ship timbers contain a variety of sulfur species. Since her restoration, the Mary Rose has been exposed to oxygen, and oxygen can convert the sulfur into sulfuric acid. This, in turn, could destroy the wood.

Dr. Eleanor Schofield from the University of Kent has been using strontium carbonate nanoparticles to de-acidify the timbers from the Mary Rose. Unstable sulfates in the wood can dissolve to form sulfuric acid. But strontium carbonate will neutralize sulfuric acid. And nanoparticles are so small – 10 to 100 nanometers – that they can penetrate into the deepest regions of the wood. At about 50 microns width, a human hair is 500 to 5000 times thicker than a nanoparticle. So, the aim is to send the strontium carbonate nanoparticles into the wood, to encounter the unstable sulfates wherever they are and convert them into strontium sulfate, which is much more stable, much less soluble, and not at all acidic.

In collaboration with SSRL scientists Drs. Ritimukta Sarangi and Apurva Mehta, Dr. Schofield used Beam Line 4-3 to determine whether the nano-strontium treatment was successful. The x-ray spectra below show the wood before and after treatment with strontium carbonate nanoparticles. By comparison to known standards, the structure of the spectra above 2490 eV allowed Dr. Schofield to determine whether the sulfates are present.

Beam Line 4-3 provided the evidence of her success. Nanoparticle treatment clearly converted the unstable sulfates into stable strontium sulfate. The Mary Rose could be rescued from acid attack. But Beam Line 4-3 found an added benefit. The nanoparticles also helped transform even the reduced sulfur into stable strontium sulfate. This surprising result shows up in the before and after spectra. Most of the reduced sulfur peak at ~2472 eV in the before spectrum has migrated up into the sulfate peak at 2482.5 eV in the after spectrum. This means most of the reduced sulfur was changed into sulfate, was then captured by the strontium, and finally was stabilized as strontium sulfate. This exciting scientific version of the Law of Unintended Consequences emerged in Dr. Schofield’s science, courtesy of Beam Line 4-3. Dr. Schofield’s work has been published in Materials Today.

P. Frank, F. Caruso and E. Caponetti, "Ancient Wood of the Acqualadrone Rostrum: Materials History through Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry and Sulfur X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy", Anal. Chem. 84, 4419 (2012)