Prions are self-propagating protein aggregates that are the infectious element of fatal neurodegenerative disease in mammals. In fungi, however, prions act as protein-based genetic elements. The fungal prion proteins have a so-called prion-forming domain (PFD) that is natively unfolded in its soluble form attached to a globular domain that can regulate the prion in cis. Upon interaction with the prion, an amyloid cross-baggregate form of the protein, the PFD, undergoes a structural rearrangement into an identical amyloid state. While considerable efforts have been devoted to the structural and functional characterization of the PFDs of fungal prions, the mechanistic basis of the cis regulatory effect of the globular domain has been only scarcely studied despite its importance in the prion propagation mechanism. The het-s/het-S fungal prion may be the most blatant example of such acis acting prion inhibitory domain1, 2. HET-s and HET-S are natural polymorphic variants of the same protein that share a functional C-terminal PFD. Yet, in contrast to HET-s, HET-S totally lacks prion-forming ability in vivo. In the filamentous fungusPodospora anserina, the HET-s prion is involved in a programmed cell death reaction termed heterokaryon incompatibility that regulates the fusion of mycelium between genetically distinct individuals.

HET-s and HET-S have two-domains: a C-terminal PFD (residues 218-289) that is both necessary and sufficient for amyloid formation and prion propagation, and an N-terminal globular domain (residues 1 to ~227) that specifies the incompatibility type ([Het-s] or [Het-S])2. A detailed analysis of the amino acid differences between HET-s and HET-S revealed that a single amino acid substitution in HET-S (H33P) converted its specificity to [Het-s] in vivo, whereas the conversion of [Het-s] to [Het-S] requires minimally two amino acid substitutions (D23A/P33H). Thus, while HET-S has a functional PFD, its globular domain exerts a prion inhibitory effect (in cis) on its own C-terminal PFD. Furthermore, the globular domain of HET-S (but not of HET-s) is essential for programmed cell death.1While the recently reported structures of the C-terminal PFD of HET-s in its fibril form have shed light on the mechanism of prion formation and propagation3, 4, many questions remain unanswered: the mechanisms of prion inhibition and of HET-s mediated heterokaryon incompatibility remain unknown, and the toxic entity that leads to cell death has not been identified. To probe these questions, a team led by Prof. S. Choe and R. Riek at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies studied the functional properties of the HET-S protein in vitro and in vivo and solved the structure of the HET-s and HET-S N-terminal domains by x-ray crystallography.

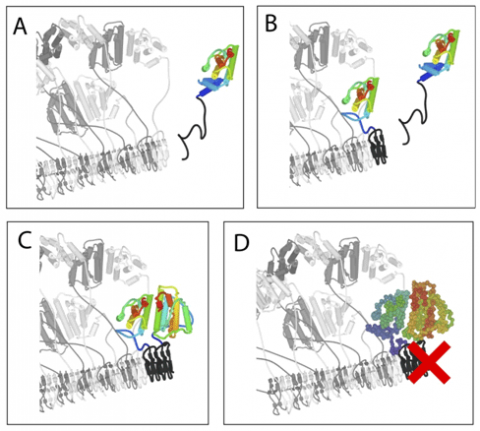

The initial lead in understanding of the mechanism came from the structures of the HET-S and HET-s globular domains that were solved using radiation from Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsrouce Beam Line 7-1. The synchrotron source was essential to the analysis due to the poor scattering from the derivatized crystals. What was immediately clear from the structures was that there were no large differences between HET-s and HET-S. This observation led them on an extensive search for specific interactions between the PFD and globular domains that might account for the ability of HET-S to regulate its own aggregation, however, none were found. Later, when more structures of HET-s were solved (mutants and alternate crystal forms) they found that the same dimer was always present, despite a wide range of crystal conditions. They then investigated the solution state of the globular domain, which was determined to be a monomer-dimer equilibrium (mostly monomer at physiological concentrations and mostly dimer at NMR or crystallization concentrations). This was telling in light of a previously studied mutation (E86K) at this interface in HET-S that was shown to have lost its toxicity in vivo. They found that this mutant (E86K) no longer formed a dimer. Finally they compared the thermal stability of HET-S and HET-s, as well as variants of each that interconvert their specificity and found that an increased thermal stability is correlated with the [Het-s] phenotype. Assimilating all of the data they were able to propose the following mechanism for prion-inhibition and activation of toxicity (Figure 1): when the HET-S PFD acquires the amyloid fold, either through the kinetically slower process of spontaneous seed formation or upon binding to the amyloid fibrils of HET-s, its globular domain is destabilized and undergoes a structural rearrangement to yield “seedless aggregates” that are incompetent for continued fibrillar growth. This model takes into account the lower thermodynamic stability and higher aggregation propensity of the HET-S globular domain. It also explains how so many different mutations can abolish HET-S activity. Mutations that destabilize the dimer, stabilize the globular domain or prevent formation of the amyloid fold in its PFD can each interfere with the proposed mechanism. Finally, the new molecular species created by the restructuring of the HET-S globular domain is a good candidate for the toxic entity that leads to cell death in the incompatibility reaction.

1. Balguerie, A., S. Dos Reis, B. Coulary-Salin, S. Chaignepain, M. Sabourin, J. M. Schmitter, and S. J. Saupe. 2004. The sequences appended to the amyloid core region of the HET-s prion protein determine higher-order aggregate organization in vivo. J Cell Sci 117:2599-610.

2.Balguerie, A., S. Dos Reis, C. Ritter, S. Chaignepain, B. Coulary-Salin, V. Forge, K. Bathany, I. Lascu, J. M. Schmitter, R. Riek, and S. J. Saupe. 2003. Domain organization and structure-function relationship of the HET-s prion protein ofPodospora anserina. EMBO J 22:2071-81.

3. Wasmer, C., A. Lange, H. Van Melckebeke, A. B. Siemer, R. Riek, and B. H. Meier. 2008. Amyloid fibrils of the HET-s(218-289) prion form a beta solenoid with a triangular hydrophobic core. Science 319:1523-6.

4. Wasmer, C., A. Schutz, A. Loquet, C. Buhtz, J. Greenwald, R. Riek, A. Bockmann, and B. H. Meier. 2009. The Molecular Organization of the Fungal Prion HET-s in Its Amyloid Form. J Mol Biol 394:119-127.

Greenwald J, Buhtz C, Ritter C, Kwiatkowski W, Choe S, Maddelein ML, Ness F, Cescau S, Soragni A, Leitz D, Saupe SJ, and Riek R "The mechanism of prion inhibition by HET-S". Mol. Cell. 38, 889-899 (2011).