Infectious diseases are caused by pathogens, and are a major cause of world-wide morbidity and mortality, especially in developing nations. While much is known about how the acquired immune system recognizes and responds to pathogens, the innate immune system, where receptors are hard-wired to interact with their ligand, is much less well understood1. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a well-characterized family of receptors that can activate the inflammatory responses of the innate immune system. These receptors are often called “pattern recognition receptors” since many TLRs bind to elements from pathogens that have a regular repeat, such as double-stranded RNA, or are both abundant and unique within pathogens, for example lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the bacterial outer membrane. In each case, a recognition mode between the TLR and the pathogen is easy to envision. TLRs can bind to the “pattern” of the RNA backbone or can have a specific binding mode to LPS. Importantly, TLRs do not undergo affinity maturation when they bind to their ligand, thus they must only bind to elements from pathogens, such as RNA backbone, that is not affected if the pathogen mutates to try to escape host defense mechanisms.

Interestingly, TLR1 and TLR2 may be involved in the recognition of outer membrane proteins.2-4 The basis for this recognition is much more difficult to envision than that of an RNA backbone since outer membrane proteins vary in sequence, structure, diameter, and conductance. Accordingly, an alternative hypothesis in the field was that TLRs bound not to the bacterial outer membrane protein itself, but to covalent lipopolysaccharide modifications of an outer membrane protein, as these modifications are common, unique to bacteria, and are something that a bacterium is unlikely to remove from its system upon mutation. As a model system to understand how TLRs recognize outer membrane proteins, we used the interaction between the TLR1/2 heterodimer and the outer membrane protein PorB from Neisseria meningitides. N. meningitidis is a causative agent of bacterial meningitis, which is a potentially deadly inflammation of the membranes lining the brain and spinal cord. We selected this system since it had previously been demonstrated in the literature that N. meningitidis PorB is not LPS modified, but is bound by cells expressing TLR24.

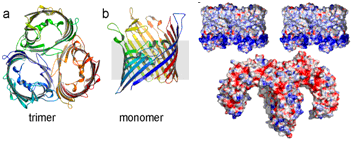

We began by determining the x-ray crystal structure of the N. meningitidis PorB by de novo methods. Like most membrane proteins, PorB was a challenge in both crystallization and structure determination, thus regular use of the SSRL facilities was critical for optimization of the samples. The structure revealed a trimeric channel with three independent pores, but did not immediately reveal what features could be recognized by the TLR1/2 receptor heterodimer. Since the structure of the chimeric TLR1/TLR2 heterodimer had previously been reported in the literature5, we used a variety of analyses to hypothesize a model for recognition. From analysis of these structures, we speculated that electrostatics contribute to complex formation.

In addition to improving our understanding of how the innate immune system recognizes bacterial outer membrane proteins, there were unexpected surprises found in the N. meningitidis PorB structure that may improve our understanding of how some commensal bacteria have evolved into pathogens. For example, during disease progression of meningitis, the PorB channel activity changes, and this alters energy harvesting in human hosts. Our structure showed how N. meningitidis PorB differs from outer membrane proteins in non-pathogenic bacteria in order to have this nefarious effect.

- Akira, S., Uematsu, S., and Takeuchi, O. (2006) Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124:783–801.

- Banerjie, P. Biswas, A., and Biswas, T. (2008) Porin-incorporated liposome induces Toll-like receptors 2- and 6-dependent maturation and type 1 response of dendritic cell. Int Immunol. 20, 1551-1563.

- Galdiero, M., Galdiero, M., Finamore, E., Rossano, F., Gambuzza, M., Catania, M.R., Teti, G., Midiri, A., and Mancuso, G.(2004) Haemophilus influenzae porin induces Toll-like receptor 2-mediated cytokine production in human monocytes and mouse macrophages. Infect Immun 72:1204–1209.

- Massari, P., Visintin, A., Gunawardana, J., Halmen, K.A., King, C.A., Golenbock, D.T.,and WetzlerLM.(2006) Meningococcal porin PorB binds to TLR2 and requires TLR1 for signaling. J Immunol 176:2373–2380.

- Jin, M.S., Kim, S.E., Heo, J.Y., Lee, M.E., Kim H.M., Paik, S.G., Lee, H., and Lee, J.O.(2007) Crystal structure of the TLR1-TLR2 heterodimer induced by binding of a tri-acylated lipopeptide. Cell 130:1071–1082.

Tanabe, M., Nimigean, C. M., and Iversion, T. M. (2010) Structural basis for solute transport, nucleotide regulation, and immunological recognition ofNeisseria meningitidisPorB PNAS, 107, 6811-6816.