Our bodies heavily rely on calcium ions (Ca2+). Their concentration in the cell cytoplasm is normally low under resting conditions, and its influx through specialized ion channels drives many functions ranging from muscle contraction, regulating heart beats, secretion of hormones and neurotransmitter, transcription of specific genes, and more. Ca2+ can enter the cytoplasm either from the extracellular space, or from intracellular stores. One such store is the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) and its membrane contains Ca2+ selective ion channels that open under controlled conditions. The main channel that regulates the Ca2+ release from the ER is the Ryanodine Receptor (RyR), a huge protein up to 2.2 MDa in size that generates the bulk Ca2+ signal required for the contraction of both skeletal and cardiac muscle.

Because Ca2+ is a very potent messenger, it is not surprising that mutations in the RyRs can lead to devastating diseases1. In skeletal muscle, one such disease is known as Malignant Hyperthermia (MH), which can lead to fatal rises in body temperature in the presence of certain anaesthetics. In cardiac muscle, mutations in RyR can cause triggered cardiac arrhythmias that may lead to sudden cardiac death. A general theme seems to be that most disease mutations cause a gain of function: the channels open prematurely, leaking Ca2+ into the cytoplasm when they shouldn’t. However, how exactly the mutations do this was unknown, simply because of a lack of high-resolution information about the channels. Most mutations cluster in so-called ‘hot spots’, three regions of the RyR sequence that are particularly prone to disease mutations. Low-resolution studies of the RyR had already been performed by other groups, providing images up to ~10Å of the entire channel2. However, at this resolution it is not possible to locate the position of individual amino acids, and in isolation it doesn’t provide insights into the disease mutations.

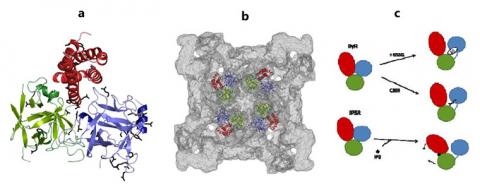

In this study, we set out to determine the high resolution structure of one of the three RyR hot spots. After purification and crystallization of the first hot spot of the skeletal muscle RyR isoform (RyR1), we used synchrotron X-rays, including X-rays originating from the SSRL, to produce diffraction to a resolution that would allow us to pinpoint individual amino acids (2.5 Å). The resulting high-resolution structure (Figure 1a) now allows us to look at the positions and effects of up to 56 different disease mutations in skeletal muscle and cardiac RyRs. Thanks to the availability of cryo-electron microscopy maps of the intact RyR, we were able to reliably dock the high-resolution structure hot spot structure into the lowresolution map (Figure 1b), underlining the power of combing high and low resolution data.

For the first time, we now have detailed insights into the structural effects of RyR disease mutations. The hot spot is folded into three separate domains (A,B and C). The mutations can be grouped into different classes: 1) mutations that are buried within individual domains and which thus affect the local folding; 2) mutations at the interface between domains A, B, and C within a channel subunit; 3) mutations between domains A and B across subunits; 4) mutations at interfaces with other RyR regions for which currently no high resolution structure is present.

In addition to locating the mutations, we can now provide a model for how RyRs likely operate in health and disease (Figure 1c). As the channel opens, many structural changes occur, including reorientations in the first disease hot spot. These changes include a relative movement of the domains, which means that particular domain-domain interactions need to be broken, a process that requires energy derived from binding a ligand (e.g.caffeine) or a protein. The disease mutations weaken the interactions, which makes iteasier for the channels to open, and thus leading to leak of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm under conditions where the channels should remain closed. This may result in deadly consequences.

The study provides a molecular template to answer many new questions that arise from the structure, and to define new strategies to interfere with their function in disease states. RyRs are known to be modulated by reactive oxygen species, and we now have a working model for how such modifications may affect the channel. Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) are another class of Ca2+ selective channels that have structural homology with RyRs. This study therefore also provides insight into the function of homologous channels. As the RyR is the largest ion channel currently known, much more high resolution information will be needed in order to fully understand its function.

1. Betzenhauser MJ, Marks AR. Ryanodine receptor channelopathies. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460(2):467-480.

2. Ludtke SJ, Serysheva, II, Hamilton SL, Chiu W. The pore structure of the closed RyR1 channel. Structure. 2005;13(8):1203-1211.

Tung CC, Lobo PA, Kimlicka L, Van Petegem F (2010) The N-terminal disease hot spot of

ryanodine receptors forms a cytoplasmic vestibule. Nature. 2010;468:585-588.