Starting in the 1970s, federal regulatory control and eventual elimination of lead-based "anti-knock" additives in gasoline decreased the level of airborne Pb in the USA by two orders-of-magnitude [1]. Blood lead levels of the USA population decreased correspondingly [2,3]. Despite this dramatic improvement in both exposure risk and body burden of Pb, the sources and health threat of the low levels of lead in our "unleaded" air remain topics of scientific and public health interest [4, 5]. Lead is a potent neurotoxin in children, particularly for toddlers whose brains are developing and who often are exposed to lead through hand-to-mouth transfer. Some researchers posit that there is no safe minimum exposure.

Societal decisions on regulation of airborne lead involve not just medical knowledge, but also an understanding of the sources of airborne lead, the cycling of lead in urban settings, and human exposure routes. Mobile (vehicular) sources represented the dominant Pb input through much of the 20th Century. With the elimination of leaded gasoline, focus in developing a new air standard for Pb has been on such point sources as smelters, lead recycling operations, manufacturing, combustion, and the continued use of leaded fuel for aviation piston engines [6].

Late last year the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) unveiled their new airborne particulate standard for lead, 0.15 mg Pb m-3 air, averaged over rolling 3-calendar-month periods [6-8]. This is an order-of-magnitude decrease from their 1970s-era standard of 1.5 mg Pb m-3 air.

In spite of this progress, it was reported that other researchers and even some members of the EPA's scientific advisory panel urged stricter limits, as low as 0.02 mg Pb m-3 air [8,9].

Instead of considering potential sources of airborne lead, a multi-disciplinary team of environmental and health scientists from the University of Texas at El Paso posed the question: what species (compounds) of Pb are actually present in our air? Their approach, using x-ray absorption spectroscopy, was to identify and, if possible, quantify the major species Pb in ambient airborne particulate matter collected in El Paso, TX, USA. The diverse team included a geochemist, a nurse, an engineer, an environmental sciences graduate student, and a retired air-quality manager.

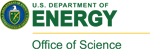

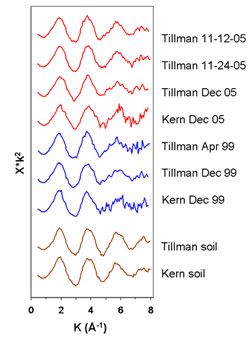

The team examined 20 samples of particulate matter (PM) collected on woven silica fiber filters in 2005 and 1999 at three sites in El Paso. The XAS experiments, conducted on Beam Lines 7-3, 10-2, and 11-2 at SSRL, proved challenging: the amount of Pb that was exposed to the beam was in the nanogram-to-microgram range. Nonetheless, it became clear that the PM samples exhibited the same overall XAFS (x-ray absorption fine structure) structure. That "fingerprint" also proved similar to those of soil samples collected nearby (Fig. 2). Comparison of the PM spectral fingerprint to those of common forms of environmental Pb turned up one prime suspect, Pb-humate (Fig. 3). Lead humate is a stable complex of Pb sorbed to humic acid; it forms exclusively in the humus fraction of soils. In Pb-humate, near-neighbor shells to the sorbed Pb are populated by O and C atoms; the lack of strong backscatterers (e.g., Pb, as in crystalline, space-repetitive Pb salts) in farther shells yields a simple spectrum and Fourier transform.

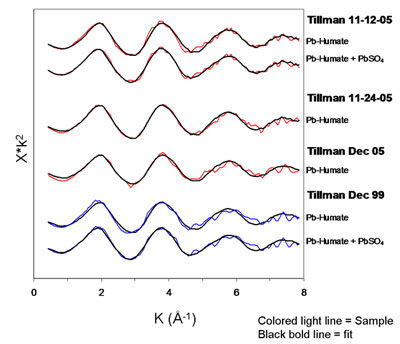

Least-squares fits of Pb-humate to the El Paso PM are striking (Fig. 4). In some samples a small amount of lead sulfate may also be present. Lead humate also provided near perfect fits to the local soil samples. Despite these compelling fits, it is possible that sorption complexes on other low-atomic-number materials (e.g., some clays) could provide computationally equivalent matches and be present in the PM. This would not, of course, have bearing on the match observed between PM and soil.

The study concluded that local Pb-contaminated soils, father than current industrial emissions, are the dominant source of Pb in contemporary airborne particulate matter in El Paso, TX. This provides direct evidence for an earlier suggestion that soil lead might explain the large discrepancy in mass-balance input-outflow models of Pb in the Los Angeles air basin [7]. Thus, earlier anthropogenic Pb releases left a legacy of contaminated soils that now leak Pb into our air in a perverse form of recycling. The process will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

From a health standpoint, the typical US inhabitant actually takes in very little Pb by simply breathing, compared to such other activities as eating. The real risk of airborne Pb is for toddlers, crawling on floors contaminated with lead-bearing dust, the indoor fallout from resuspended Pb-contaminated soil.

The bottom line? At some point, meeting further legislative restriction of Pb in airborne particulate matter could require the remediation or removal of Pb-contaminated soil to prevent its resuspension into the air. That will prove very expensive. And for those toddlers, worth it.

[1] Davidson CI, Rabinowitz M (1992) Lead in the environment: From sources to human receptors. In: Needleman HL, editor. Human Lead Exposure. Boca Raton: CRC, pp. 65-86.

[2] Annest J, Dirkle J, Makuc C, Nesse J, Bayse D, et al. (1983) Chronological trend in blood lead levels between 1976 and 1980. N Engl J Med 308: 1373-1377.

[3] ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry) (1988) The Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United States: A Report to Congress. Atlanta: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, ATSDR.

[4] Anon (2007) Tougher standard for lead in air recommended. Chem Eng News 85(46): 39.

[5] Stokstad E (2008) Panel: EPA proposal for air pollution short on science. Science 319: 146.

[6] US Environmental Protection Agency (2008c) Environmental Protection Agency 40 CFR Parts 50, 51, 53 and 58 [EPA-HQ-OAR-2006-0735; FRL-_____- _] RIN 2060-AN83 National Ambient Air Quality Standards for Lead. Available: http://epa.gov/air/lead/pdfs/20081015_pb_naaqs_final.pdf [accessed 7 November 2008].

[7] Harris AR, Davidson CI (2005) The role of resuspended soil in lead flows in the California South Coast Air Basin. Environ Sci Technol 39: 7410-7415.

Pingitore Jr NE, Clague J, Amaya MA, Maciejewska B, Reynoso JJ (2009) Urban Airborne Lead: X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Establishes Soil as Dominant Source. PLoS One 4(4): e5019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005019 http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0005019.