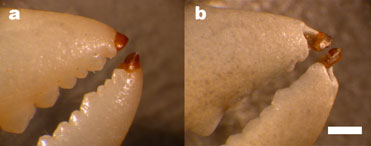

Invertebrates modify their jaws, claws, carapaces and other mechanical structures with a variety of inorganic materials. One of the best-known examples is the calcified cuticle of crabs. We have found that many crabs also employ an uncalcified bromine-rich biological material at the tips of their claws and legs (Figure 1). The bromine-rich material is a member of a class of structural biological materials enriched with heavy elements: iron, manganese, copper, zinc, bromine, and iodine. Little is known about the biochemistry of these materials or the mechanical properties that they convey. Crabs afford an opportunity to investigate the molecular structure and to test the mechanical properties of one of these heavy element biomaterials for comparison with properties of the more familiar calcified cuticle in the same organism. We compared abrasion resistance, coefficient of kinetic friction, energy of fracture, hardness, modulus of elasticity and dynamic mechanical properties for unenriched, calcified, and bromine-rich cuticle.

Our results suggest that the greatest advantage of bromine-rich cuticle over calcified cuticle is resistance to fracture (the energy of fracture is about an order of magnitude greater than for calcified cuticle). The greatest advantage relative to unenriched cuticle, was a factor of about 1.5 greater hardness and modulus of elasticity, making the tips harder and more stiff than acrylic glass. The claw tips gain increased fracture resistance from the orientation of the constituent laminae and from the viscoelasticity of the materials.

![Figure 2.The inset is an image of the bromine Ka fluorescence emission intensity [in arbitrary units ranging from zero (dark blue) to highest (dark red)] recorded on a crab claw tip specimen by scanning fluorescence x-ray microscopy with excitation at 14 keV. The x-ray beam size was approx. 10 x 10 mm and the raster step size was 10 mm. The horizontal dimension of this image is 2.0 mm. The upper convex edge of the bromine emission coincides with the external surface of the crab claw tip while the bottom represents the dissection region. Four spots across the bromine content of this specimen were selected to collect bromine XAS edge spectra and these spectra (single first sweeps) are displayed above the inset image. The shape and structure of these edges are sensitive to the local bromine environment and all appear identical to one another and very similar to the edge observed in the bulk bromine XAS experiment, suggesting a homogeneous bromine environment. Figure 2.](/content/sites/default/files/images/science/highlights/2009/crab_claws_fig2.jpg)

It may not be surprising that smaller organisms would employ fracture-resistant materials in the thin regions of their "tools". Smaller organisms may be subjected to the same forces from the environment, predators, and prey as larger organisms, but the smaller cross sections of their "tools" make them more susceptible to fracture.

So how is this hard but fracture-resistant material constructed? We used x-ray microscopy and both bulk and microprobe x-ray spectroscopy to examine the Br local environment and distribution in the crab claw tips. X-ray fluorescence microscopy showed a relatively homogeneous distribution of Br throughout the claw tip and the Br K edge spectra were virtually identical regardless of the position of the x-ray beam along the tip (Figure 2). Analysis of bulk Br EXAFS identified a local Br environment resulting from brominated phenyl rings, which we hypothesize to represent bromotyrosine.

The mechanism by which the bromine (and other heavy elements in other organisms) modifies the mechanical properties is not understood. One possibility is that bromine makes the material harder and stiffer by increasing the cross-links between proteins. Another, more speculative, possibility is that the high mass density of the heavy elements improves resistance to fracture. The attachment of many heavy bromine atoms to many phenyl rings along the protein would reduce the resonant frequencies of certain low frequency large-scale molecular motions (such as standing torsional waves over the length of the molecule). If these resonances were lowered to overlap more with the range of frequencies associated with impacts, then bromination might improve damping of impact energy.

A good example of the bromine biomaterial can be investigated the next time you eat a Dungeness crab. Notice that the sharp tip of the leg is a cap of translucent material that is very different from the rest of the crab. It is very difficult to break the tip, even though it is very thin, stiff and hard.

Humans are just starting to try to engineer tiny machines and tools, and we have a lot still to learn from organisms that have coped with being small for millions of years.

R. M. S. Schofield, J. C. Niedbala, M. H. Nesson, Y. Tao, J. E. Shokes, R. A. Scott and M. J. Latimer, "Br-rich Tips of Calcified Crab Claws are Less Hard but More Fracture Resistant: A Comparison of Biomineralized and Heavy-element Biomaterials", J. Struct. Biol. 166, 272 (2009)