Structurally incorporated impurities have been shown to have systematic effects on the rate of the thermally driven transformation in titania nanoparticles [1-4]. The anatase-to-rutile transformation is slowed when anatase nanoparticles are doped with a cation of valence > +4, but favored when the valence < +4. Based on these observations, Y3+ dopants should promote the anatase-to-rutile transformation. However, prior studies showed that the transformation is inhibited by Y3+ impurities [1,2], without explaining this observation. In a study led by the scientists of University of California Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, extended x-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) experiments on yttrium-doped titania nanoparticles were conducted for determining the local structural environment of Y3+ impurities. The experiments were developed in collaboration with SSRL beamline scientists at BLs 10-2 and 11-2.

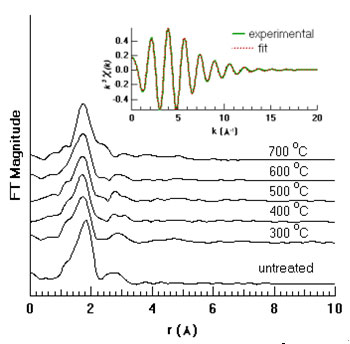

EXAFS setup is shown in Figure 1. The measurements at the Y K-edge (17300 eV) were made up to k = 12 Å-1. A Lytle detector was used with helium gas flowing through the sample chamber and Ar gas through the detector chamber. The x-ray energy was calibrated with Y foil before the experiments. For harmonics rejection the monochromator was detuned by 50%. Because the doping concentration of yttrium is relatively low, fluorescence mode was used.

The fit results (Figure 2) indicate that the Y impurity does not exist as (YxTi)O2-3x/2, i.e., the Y impurity is not structurally incorporated. This differs from the cases of doping TiO2 with some other ions (e.g. Cr3+, Fe3+), where impurities are distributed within the nanoparticles [2,3]. The reason why Y3+ does not substitute for Ti4+ in TiO2 nanoparticles is very likely the difference in the size of the Y3+ (0.892 Å to 1.10 Å) and Ti4+ ions (0.53 Å to 0.605 Å) [5]. Moreover, the first shell scattering in the EXAFS data is well fitted by Y-O bonds of length ~ 2.3 Å, a nearly 20% mismatch with the Ti-O bond lengths in the nanoparticles (1.92 Å and 1.96 Å) [6]. For heat-treated nanoparticles, the first shell Y-O coordination number is six, consistent with the yttrium oxide (Y2O3) structure. However, the characteristic XRD peaks of Y2O3 are not detected from our samples indicating that, if present, individual clusters of this phase should be smaller than ~1 nm. Furthermore, the Y-O bond length (~2.3 Å) is larger than that of bulk Y2O3 (2.2749 Å) [7]. It can be conclude that yttrium impurities are mostly present as individual, oxygen-coordinated atoms at the titania surface (i.e., as YO6 groups) and about 15% of the surface oxygen sites are bound to Y.

Together with the observation of the structural modification and phase transformation retardation in the complementary wide-angle x-ray scattering experiments for the study, it has been found that the low concentrations of yttrium surface impurities on nano-anatase reduce surface energy and inhibit nanoparticle growth over a large temperature range. As a consequence, the anatase phase is also stabilized, as the anatase-to-rutile transformation does not occur below 700 °C. The findings demonstrate the effectiveness of surface bound impurities of stabilizing nanoparticle size and phase, an issue of great importance for retaining the materials properties of nanoscale catalysts that operate at high temperatures.

- J. F. Banfield, B. L. Bischoff, and M.A. Anderson, Chem. Geo. 110, 211 (1993)

- B. L. Bischoff, Thermal Stabilization of Anatase Membranes, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1992.

- Y. H. Zhang, and A. Reller, J. Mater. Chem. 11, 2537 (2001).

- H. Yamashita et al., J. Synchrotron Rad. 6, 451 (1999).

- F. D. Bloss, Crystallography and Crystal Chemistry (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1971).

- L. X. Chen et al., J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 10688 (1997).

- N. Thromat et al., Phys. Rev. B 44, 7904 (1991).

Bin Chen, Hengzhong Zhang, Benjamin Gilbert, Jillian F. Banfield, "Mechanism of Inhibition of Nanoparticle Growth and Phase Transformation by Surface Impurities", Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 106103 (2007).