Nanoporous or mesoporous inorganic materials with homogeneous pore sizes have found broad applications in separations, as supports for size selective catalysis, and as low dielectric materials. For all of these applications, it is the pore space that is important, and so the inorganic framework is generally formed from a simple material like silica or another oxide. In an effort to extend the range of potential applications for this class of porous materials, research at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have recent shown that solution phase templating routes can be used to form ordered nanoporous versions of classic semiconductors such as germanium.

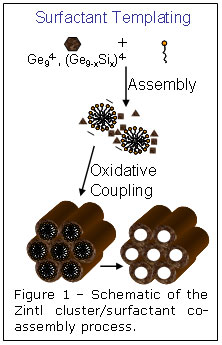

Surfactant templating is a method that has been successfully employed to produce nanoporous inorganic structures from a wide range of oxide-based material. Co-assembly of inorganic precursors with amphiphilic organic molecules is followed first by inorganic condensation to produce a rigid amorphous framework and then by template removal to produce a mesoporous solid. In a new advance to this field, researchers at UCLA have shown that it is possible to use surfactant-driven self-organization of soluble Zintl clusters to produce periodic, nanoporous versions of classic semiconductors such as amorphous Ge or Ge/Si alloys. They specifically employed derivatives of the anionic Ge94- cluster, which was co-assembled with cationic surfactants to produce an ordered nanostructured composite. Oxidation of the reduced Zintl clusters to neutral germanium cross-linked the germanium framework and released the cationic surfactant, resulting in a periodic porous semiconductor with a pore diameter of ~3 nm and surface areas as high as 500 m2/g. The inorganic/surfactant co-assembly process is shown schematically in figure 1.

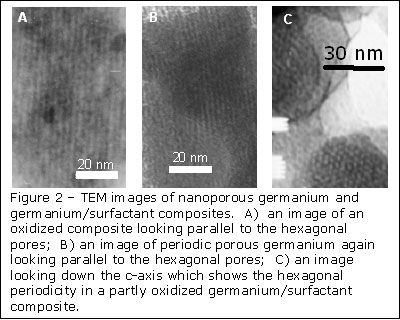

To understand the mechanism of self-assembly and to characterize their materials, UCLA researchers used a combination of many experiments, including transmission electron micro-scopy (TEM), X-ray diffraction, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and gas porosimetry. An example of TEM images of some of the materials are shown in figure 2. One other particularly useful characterization tool was germanium extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS). EXAFS experiments were carried out at beam lines 4-1 and 6-2 at SSRL. The experiments allowed the UCLA researchers to understand the local structure in their composite materials before and after oxidation and to confirm that the final porous materials contained tetrahedrally bonded germanium, just like bulk amorphous germanium.

While most of the work to date has focused on developing the fundamental self-organization required to produce these materials, a broad range of new applications are potentially enabled by these materials. They both absorb and emit light at near infra-red wavelengths. Moreover, the band gap can be tuned both by tuning the thickness of the germanium walls (an effect known as quantum confinement) and by changing the composition of the framework. For example, by analogy with bulk group IV semiconductors, if the Zintl clusters made from a mixture of silicon and germanium are used, the resulting porous material has a significantly blue shifted band gap. The materials also appear to conduct electricity almost as well as bulk amorphous germanium, despite their nanoporous architecture. UCLA researchers are currently exploring a variety of applications for these materials, including nanoscale solar cells and adsorption based chemical sensors. Because the semiconductor surface is exposed and accessible in these materials, they have the potential to interact with a variety of species in ways that could eventually lead to a range of novel nanostructured devices.

"Hexagonal Nanoporous Germanium through Surfactant-Driven Self-Assembly of Zintl Clusters" D. Sun, A.E. Riley, A.J. Cadby, E.K. Richman, S.D. Korlann, and S.H. Tolbert, Nature, 441, 1126-1130, (2006).