The two common chromium oxidation states, Cr(III) and Cr(VI), differ greatly in their impacts on the environment and human health. Cr(III) in most common forms in the environment is normally not a major concern to public health because it is not very soluble and therefore poorly adsorbed by the body. In contrast, Cr(VI) in the form of chromates is usually readily soluble and, because of its oxidizing capability, can have severe adverse effects on the human body, including cancerous tumor formation and gene damage. Although chromium is normally only present at the 10 ppm level in coal, the approximately one billion tons of coal used annually for electricity generation in the U.S. implies that about 10,000 tons of chromium are processed through electricity generating plants each year, with most of it ending up as a component in fly-ash, the major waste product from coal combustion. Disposal practices for coal-derived fly-ash vary greatly, but much of it is stored in isolated surface piles or in impoundments. Even so, there is still a finite risk that elements such as chromium may leach and eventually contaminate local groundwater and drinking water supplies./p>

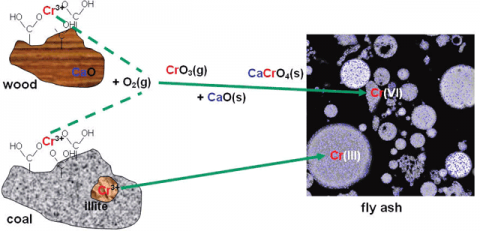

Normally, chromium is found in coal entirely in the trivalent oxidation state, Cr(III), as a component in clay minerals associated with coal, such as illite or chlorite; or as small-particle chromium oxide (Cr2O3) or oxyhydroxide (CrOOH) within the carbonaceous components of coal; or more rarely as chromite (FeCr2O4), as a result of special geological circumstances. Only in an unusual coal from New Zealand has a significant Cr(VI) occurrence (as lead chromate, PbCr2O4) been documented for chromium. Consequently, at the levels chromium is normally found in coal (between 5 and 25 ppm) and because Cr(III) is relatively non-hazardous to humans, chromium in coal is not considered a serious health risk. However, during commercial coal combustion, coal is burned with excess air to raise heat to generate steam for turbines that produce electrical energy. In the process, significant quantities of ash are created from the incombustible inorganic components in coal. Furthermore, there is the potential for greatly increasing the health risk associated with chromium because not only can its concentration in the ash be increased by up to 10 times compared to that in the original coal, but Cr(III) can also be oxidized during coal combustion to Cr(VI), which poses a much greater threat to public health.

In order to accurately assess the risk posed by coal-derived chromium to public health, it is important to be able to track how chromium behaves during coal combustion and to establish how it occurs in ash byproducts and how it behaves in ash disposal situations. Furthermore, owing to their very different properties with respect to leachability from fly-ash, as well as their different effects on human health, it is essential to be able to determine the proportions and forms of the two different chromium oxidation states in fly-ash for realistic risk assessments. A team of researchers from KEMA in the Netherlands, the University of Kentucky, and the University of Twente in the Netherlands recently took a multi-faceted approach to determine these factors that combined a modeling approach based on thermodynamic calculations of the behavior of chromium in coal and coal/biomass co-combustion, ash leachability experiments, and experimental determinations of the Cr(VI)/total Cr ratio in fly-ash based on XAFS spectroscopic measurements. As has been well-established in a number of studies, the relative proportions of Cr(VI) and Cr(III) in fly-ash and other environmental materials can be readily determined from the height of the pre-edge peak in normalized chromium XANES spectra with a precision of about ±2%. For this study, such measurements were made at SSRL Beam Line 4-3.

Using the XANES method, Cr(VI) as a percentage of the total Cr was determined to be less than 10% in fly-ash when derived from commercial pulverized combustion of bituminous coals. However, it was found to be significantly higher (up to 30%) in ash from combustion of subbituminous and other lower-rank coals and also from coal and wood co-firing. Thermodynamic calculations and other considerations indicate that the stability of Cr(VI) in the form of alkali and alkaline earth chromates (e.g. Na2CrO4, BaCrO4, CaCrO4) may account for this difference because such elements are more abundant and present in more easily volatilized forms in lower-rank coals. A similar explanation may apply to co-firing of coal and wood. The results also indicate that the combustion conditions, particularly the air/fuel ratio, are important in determining the percentage of chromium as Cr(VI). Investigations of the aqueous leachability of chromium from fly-ash indicate that little of the Cr(III) is leachable, since much of the Cr(III) in ash is present in insoluble aluminosilicate glass or oxide forms. However, significant fractions of Cr(VI) may be leachable depending on the specific chromate formed.

Measurements of the Cr(VI)/total Cr ratio in coal-derived fly-ash, made directly and non-destructively by XAFS spectroscopy at SSRL Beam Line 4-3, are providing the necessary information to validate thermodynamic modeling of the behavior of chromium during coal combustion. Results based on this combined approach suggest that leachable Cr(VI) contents in the ash could be minimized by better control on the excess air present during combustion and possibly by additives that promote the formation of insoluble chromate species.

Arthur F. Stam, Ruud Meij, Henk te Winkel, Ronald J. van Eijk, Frank E. Huggins, Gerrit Brem. Chromium Speciation in Coal and Biomass Co-Combustion Products. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2011, 45 (6), 2450-2456. DOI: 10.1021/es103361g