Iron, the most abundant transition metal on Earth’s surface, is important in numerous biogeochemical processes. Iron minerals often dominate the reactivity of soils, sediments, rock matrices, and engineered environments (including permeable reactive barriers) and any environmental or geological sample will likely contain iron in one or more of its three valence states (Fe0, Fe(II), and Fe(III)) in numerous chemical forms.

Identifying the valence state and mineral speciation of iron in the solid phase constituents of environmental and geological samples is crucial to understanding the reactivity of such samples. Geomicrobiologists are also particularly interested in how Fe changes form as rocks react with water, because the oxidation of Fe can provide energy for microbial growth under oxic conditions, or can result in the production of hydrogen gas as an alternative energy source under anoxic conditions. However, identifying changes in the valence state and mineral speciation of iron in the solid phase constituents of environmental, geological and biological samples is highly challenging.

Recently, a team of researchers from the University of Colorado–Boulder’s Department of Geological Sciences, combined powdered basalt, Fe(III)-oxides, and zero valent iron with artificial seawater in closed vessels and incubated them at 55°C for both short (48 hours) and long (~1 year) reaction times. The team monitored the gaseous and aqueous chemistry of the system over time through routine sampling procedures. However, the small amount of starting material used, small particle size, and moderate reaction temperature greatly limited the amount of solid phase alteration products. Thus, they needed to be able to rapidly profile the oxidation state, speciation, and distribution of iron on a microscale.

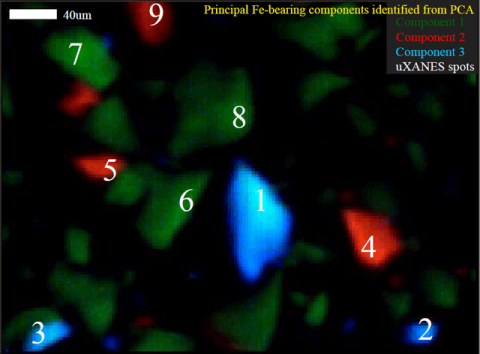

At Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource Beam Line 2-3, the team worked with SSRL Staff Scientist Sam Webb to develop an integrated approach to data collection and processing of synchrotron-based x-ray fluorescence microprobe mapping (mXRF) and spot x-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (mXANES) to identify and map unique iron-bearing components within the system. This method and the results of the team’s water-rock reaction experiment were recently published in Environmental Science & Technology (Mayhew et al., 2011). The team collected mXRF maps at multiple energies within the iron K-edge specifically chosen to highlight the differences in iron speciation. Principal components analysis (PCA) was conducted on the multiple energy maps to determine the locations and distributions of different iron-bearing species. Multiple energy mapping and PCA are commonly employed in soft x-ray synchrotron-based analyses but these techniques have not yet been extensively applied to hard x-ray synchrotron investigations.

The component maps were used to guide the locations of mXANES analyses, ensuring that the team sampled the entire diversity of iron-bearing species and was not biased by elemental hotspots. These mXANES analyses were then used to define the spectra of end-member XANES. These end member XANES were least squares fit with iron model compounds to identify the speciation of iron represented by the spectra. In order to visualize the distribution of the different iron species, the team performed least squares fitting of the data from the multiple energy maps with the end member spectra, giving a spatial distribution of the iron speciation on the micro-scale in each sample. Using this method, they detected, identified and mapped all of the starting materials in both the short and long term reactions. They were also able to identify incipient reaction products in the 48-hour sample and the precipitation of new secondary iron-phyllosilicates after ~1 year of reaction. Many of the mXANES spectra corresponding to these secondary phases were collected from non-descript, low fluorescence particles; had these particles not been indicated in maps of unique components they may not have been chosen for further investigation and the growth of these alteration products may have been overlooked. The application of this technique is not limited to iron-speciation but will also be useful for investigations into the speciation of other redox active elements in a wide range of both natural and engineered environments.

This work was conducted at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, through the Structural Molecular Biology Program, supported by DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and the National Institutes of Health.

L. E. Mayhew, S. M. Webb, and A. S. Templeton,“Microscale Imaging and Identification of Fe Speciation and Distribution during Fluid–Mineral Reactions under Highly Reducing Conditions” Environ. Sci. Technol., 45 4468 (2011).DOI: 10.1021/es104292n