| ||

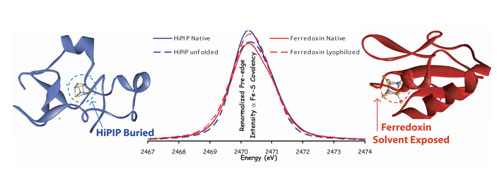

| Schematic representation of the common active-site iron-sulfur cluster structural motif. |

To learn more about this research see the full scientific highlight at:

http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/research/highlights_archive/iron-sulfur_clusters.html

2. Science Highlight —

A Step Toward Understanding High-Temperature Superconductors

(contacts: D.H. Lu, dhlu@slac.stanford.edu; Z.-X. Shen, zxshen@stanford.edu)

|

| a, Underdoped sample with Tc = 75 K. b, Underdoped sample with Tc = 92 K. c, Overdoped sample with Tc = 86 K. At 10 K above Tc there exists a gapless Fermi arc region near the node. [see larger image and more detailed caption at Nature]. |

Certain materials become superconductors-that is, losing all resistance to electric current-when they become colder than their transition temperature. So far, the warmest transition temperature recorded is minus 164 degrees Fahrenheit. Below the transition temperature, the electrons pair up. This pairing reduces the energy of the electrons. The strength of pairing is characterized as a superconducting gap in the single particle excitation spectrum, which is found below the transition temperature in both conventional and high-temperature superconductors.

In high-temperature superconductors, scientists also observe a gap above the transition temperature, called the pseudogap. So far it has been unclear whether the two gaps are unrelated, or if the pseudogap is a precursor to the superconducting gap. Using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy to measure the energy gap at different temperatures and momenta, Shen and colleagues found that the pseudogap and the superconducting gap coexist and exhibit different temperature dependence. Therefore, the two gaps seem to have different origins. This should provide an important step toward unveiling the mystery of the pseudogap phenomena.

http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/research/highlights_archive/high-tc_07.html

In preparation for a key program review of SSRL by the DOE Office of Basic

Energy Sciences and for our Annual NIH, NCRR/Biomedical Technology Program

(BTP) Progress Report, SSRL needs your support. Please provide us, by December

5, with a list of publications, major awards and invited lectures for work

based at least in part on use of SSRL resources for years 2005-2007. Please

send your list of publications by email to lisa@slac.stanford.edu or by using

the web form at:

http://smb.slac.stanford.edu/forms/reporting/form_publication.shtml.

Please also flag those that you view as being "high profile, high impact" with a

sentence explaining the impact.

4.

JCSG Celebrates Its 500th Structure

SSRL has contributed to the development of robotic hardware to process and

evaluate the crystal samples, enabling fast sample turn-around at the beam

lines, and has generated novel software programs for high through-put structure

determination. "Because the beam line is fully automated, we can control

almost every step in our experiment from any computer," said Jessica Chiu, who

manages crystal screening and data collection activities at SDC. "We can be at

home, or in another country, and still screen crystals around the clock. This

allows us to attain maximal throughput at the beam lines with minimal human

intervention."

The determination of 500 structures is a tremendous accomplishment, and a

testament to the talented scientific team and to the success of their

automated, highly efficient operation. "We've doubled the rate at which we

solve new structures since 2005," Deacon reported, "and we're still getting

faster. But we won't compromise quality. The best way to speed things up is to

get the best quality data you possibly can."

More information on all of the structures solved and deposited by the JCSG can

be found at the JCSG Structure Gallery.

JCSG is funded by the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences,

Protein Structure Initiative U54GM074898. http://www.jcsg.org/

There are new procedures related to international shipments, so please contact

us in advance if you are planning to ship samples, equipment or other

scientific items from SSRL to a location outside of the US following your beam

time at SSRL (for example, to return dewars to a collaborator or your home

institution).

__________________________________________________________________________

SSRL Headlines is published electronically monthly to inform SSRL users,

sponsors and other interested people about happenings at SSRL. SSRL is a

national synchrotron user facility operated by Stanford University for the

U.S. Department of Energy Office of Basic Energy

Sciences. Additional support for

the structural biology program is provided by

the DOE

Office of Biological and Environmental Research, the NIH

National Center for Research Resources and the NIH Institute for General Medical

Sciences. Additional information about

SSRL and its operation and schedules is available from the SSRL WWW

site.

__________________________________________________________________________

To leave the SSRL-HEADLINES distribution, send email as shown below:

To: LISTSERV@SSRL.SLAC.STANFORD.EDU

Subject: (blank, or anything you like)

The message body should read

SIGNOFF SSRL-HEADLINES

That's all it takes. (If we have an old email address for you that is

forwarded to your current address, the system may not recognize who

should be unsubscribed. In that case please write to

ssrl-headlines-request@ssrl.slac.stanford.edu and we'll try to figure out

who you are so that you can be unsubscribed.)

If a colleague would like to subscribe to the list, he or she should send

To: LISTSERV@SSRL.SLAC.STANFORD.EDU and use the message body

SUBSCRIBE SSRL-HEADLINES

3.

Call for User Publications, Awards, Invited Lectures

(contacts: L. Dunn, lisa@slac.stanford.edu)

Lists of publications reported to SSRL to date and sample acknowledgment

statements can be found at: http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/pubs/

Biochemistry and Cell Biology December cover image

(85: 537-542 (2007)).

Inset image: Synchrotron X-ray fluorescence mapping reveals the asymetric

distribution of iron in an intact Xenopus laevis oocyte.

Image: Popescu et. al, University of Saskatchewan Background image: Human

breast cancer cells MCF-7 immunostained for microtubules (alpha-tubulin) in

green and transcription factor Sp1 in red, with nuclei in blue. Image provided

by Shihua He, University of Manitoba.

Science October 19 cover

image (318, 430 (2007)).

Structure of a gold nanoparticle in which the central atoms are packed in a

decahedron, surrounded by additional layers of gold atoms in unanticipated

geometries. Gold atoms, gold; sulfur atoms, blue; carbon atoms, white; oxygen

atoms, red; the superimposed red mesh depicts the electron-density distribution

determined by x-ray crystallography. Image: Pablo D. Jadzinsky

and Guillermo Calero.

Molecular Cell October 12 cover image

(28, 41 (2007)).

The high-resolution structure of the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum Hsp90

chaperone GRP94 with bound ATP. The extent to which a common mechanism applies

to all Hsp90 chaperones has been controversial. In cytosolic Hsp90s, ATP

binding results in N-terminal dimerization that is critical for ATP hydrolysis

and subsequent chaperone function. Dollins et al. show that

nucleotide-bound GRP94 adopts a conformation that precludes N-terminal

dimerization yet demonstrate GRP94-catalyzed ATPase activity using kinetic

analyses, suggesting that nucleotide binding is not the major driving force for

catalytically productive conformational changes.

—SLAC

Today article by Elizabeth Buchen

On October 29, the Joint Center for Structural Genomics (JCSG)-in which SLAC

plays an integral role-celebrated a major milestone as it deposited its 500th

unique protein structure into the Protein Data Bank (PDB). A protein's 3D

structure dictates its function-including how it interacts with other proteins,

how it catalyzes chemical reactions and how it might be inhibited or activated

by drugs. By determining structures representative of large protein families

from a wide range of genomes, the JCSG seeks to illuminate key aspects of

biology, chemistry and medicine that span from neurodegenerative disease to

human evolution.

Ashley Deacon loads samples of crystallized proteins into an automated sample

mounting system.

The process of depositing a protein structure into the PDB begins with the

Bioinformatics Core (based at the University of California San Diego and the

Burnham Institute for Medical Research) selecting the targets to be

investigated and the Crystallomics Core (based at The Scripps Research

Institute and the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation)

producing soluble proteins that are then crystallized. Researchers at SLAC's

Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) then use x-ray diffraction to

map out the atomic structure of each crystallized protein. This Structure

Determination Core (SDC) group determines the 3D structures and deposits the

structural coordinates and diffraction data into the PDB, where they are freely

available to the scientific community.

"Together, the Institutes in our consortium have established a very effective

pipeline," said SLAC's Ashley Deacon, who leads the SDC. "We have developed

new technologies and automated the various steps of the process to scale up not

only production, but also to increase the efficiency, lower the cost and

increase the quality of the structures determined."

5.

Planning Any International Shipments?

(contacts:

C. Knotts, knotts@slac.stanford.edu; L. Dunn, lisa@slac.stanford.edu)

7.

User Administration Update

(contact:

C. Knotts, knotts@slac.stanford.edu)

Macromolecular Crystallography Proposals due December 1: If you are interested

in submitting a proposal for the December 1, 2007

deadline for time on

macromolecular crystallography beam lines, see:

http://smb.slac.stanford.edu/public/forms/becominguser/

X-ray/VUV Beam Time Requests due December 7: Please submit your requests for

X-ray/VUV beam time for the February-May 2008 scheduling period.

http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/users/user_admin/xray_btrf.html

http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/users/user_admin/vuv_btrf.html

Start your holiday shopping on your next visit to SSRL: When you check in for

beam time, check out our Texas Orange t-shirts commemorating the first

joint SSRL and LCLS users' conference. On sale now - just $10 - while supplies

last. See Michelle Steger Bldg. 120, Rm. 219.

SSRL Welcome

Page | Research

Highlights | Beam Lines | Accel

Physics

User

Admin | News & Events |

Safety Office