|  |

|

Figure 1.

Schematic repre-sentation of the common active-site iron-sulfur cluster

structural motif.

| |

Proteins containing Fe4S4 iron-sulfur clusters are ubiquitous in nature and

catalyze one-electron transfer processes. These proteins have evolved into two

classes that have large differences in their electrochemical potentials: high

potential iron-sulfur proteins (HiPIPs) and bacterial ferredoxins (Fds). The

role of the surrounding protein environment in tuning the redox potential of

these iron sulfur clusters has been a persistent puzzle in biological electron

transfer [1]. Although HiPIPs and Fds have the same iron sulfur structural motif

- a cubane-type structure - (Figure 1), there are large differences in their

electrochemical potentials. HiPIPs react oxidatively at physiological

potentials, while Fds are reduced. Recently, sulfur K-edge x-ray absorption

spectroscopy (XAS; measured at SSRL beam line 6-2) has been used to uncover the

substantial influence of hydration on this variation in reactivity in a

collaborative effort led by Stanford Chemistry and Photon Science researchers

Edward I. Solomon, Keith O. Hodgson and Britt Hedman [2].

|  |

|

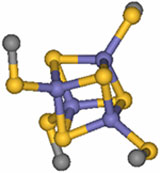

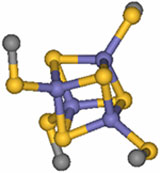

Figure 2.

Pre-edge region of the Sulfur K-edge XAS data for a model (black), wild-type

C.

vinosum HiPIP (in blue), unfolded C. vinosum HiPIP (in dashed brown), wild-type

B. thermoproteolyticus (Bt) Fd (in red) and lyophilized Bt Fd (in dashed

green).

| |

The sulfur-K XAS pre-edge involves excitation of S 1s electrons to the

unoccupied valence orbitals formed by interaction of the Fe 3d orbitals with

the S 3p orbitals [3]. Since the transition is localized on the sulfur, the

pre-edge provides a direct measure of S 3p character in the metal d orbitals

(i.e. covalency). In this study, which follows several years of developing the

methodology behind this approach [4], S K-edge XAS was used to examine the

changes in covalency in native and perturbed (lyophilized Fd and unfolded

HiPIP) protein environments. These experiments show that the Fe-S covalency is

much lower in natively hydrated Fd active sites than in HiPIPs, but increases

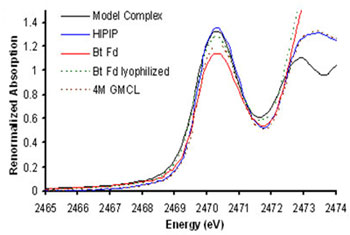

upon water removal (Figure 2). Similarly, HiPIP covalency decreases upon

unfolding, exposing an otherwise hydrophobically shielded active site to water

(Figure 3). These results demonstrate that Fe-S covalency is a direct

experimental marker of the local electrostatics due to H-bonding. Studies on

related model compounds and accompanying density functional theory (DFT)

calculations support a correlation between Fe-S covalency and ease of

oxidation, which suggests that differential hydration accounts for most of the

difference between Fd and HiPIP reduction potentials. This raises the

intriguing possibility that oxidation/reduction potentials can be regulated by

protein/protein and protein/DNA interactions that effect cluster hydration.

|  | |

|

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the iron-sulfur cluster reduction potential tuning

by desolvation.

| | |

Primary Citation:

A. Dey, F. E. Jenney, Jr., M. W. W. Adams, E. Babini, Y. Takahashi, K.

Fukuyama, K. O. Hodgson, B. Hedman and E. I. Solomon, "Solvent Tuning of

Electrochemical Potentials in the Active Sites of HiPIP Versus Ferredoxin",

Science 318, 1464 (2007)

References:

-

K. Fukuyama, Handbook of Metalloproteins; A. Messerschmidt, R. Huber, T.L.

Poulos, K. Wieghardt, Eds, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 543 (2001).

-

A. Dey, F.E. Jenney Jr., M.W.W. Adams, E. Babini, Y. Takahashi, K. Fukuyama,

K.O. Hodgson, B. Hedman, E.I. Solomon, Science 318, 1464 (2007).

-

T. Glaser, B. Hedman, K.O. Hodgson, E.I. Solomon, Acc. Chem. Res.

33, 859

(2000).

-

B. Hedman, K.O. Hodgson, E.I. Solomon, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112,

1643 (1990); E.I. Solomon, B. Hedman, K.O. Hodgson, A. Dey, R.K. Szilagyi, Coord.

Chem.

Rev., 249, 97 (2005).

|

| PDF

Version | | Lay Summary | |

Highlights Archive

|

| SSRL is supported

by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL

Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy,

Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes

of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology

Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |

|