|

Ångström: One Ångström

is 10-10 meters, 1/10 of a nanometer. Atoms in molecules are

separated by about 1 Ångström. Since the wavelength of LCLS

x-rays are also in the range of 1 Ångström, the distribution

of x-rays scattered by an atom is influenced by the placement of its neighbor

atoms in a molecule. For this reason, x-ray scattering measurements provide

information on the structure of a molecule.

The wavelength of an x-ray is directly connected with the quantum of

energy that it can transfer to an atom if it is absorbed. The 1.5 - 15

ångström operating range of the LCLS corresponds to x-ray energies

from 8 keV to 800 eV. This means that LCLS x-rays can kick inner (K- and

L-) shell electrons out of most elements encountered in nature. Kicking

out electrons is the primary mechanism by which the LCLS delivers heat

to a sample.

There are about as many Ångströms in a centimeter as there are

kilometers between the planet Venus and the sun.

There are about as many Ångströms in a centimeter as there are

kilometers between the planet Venus and the sun.

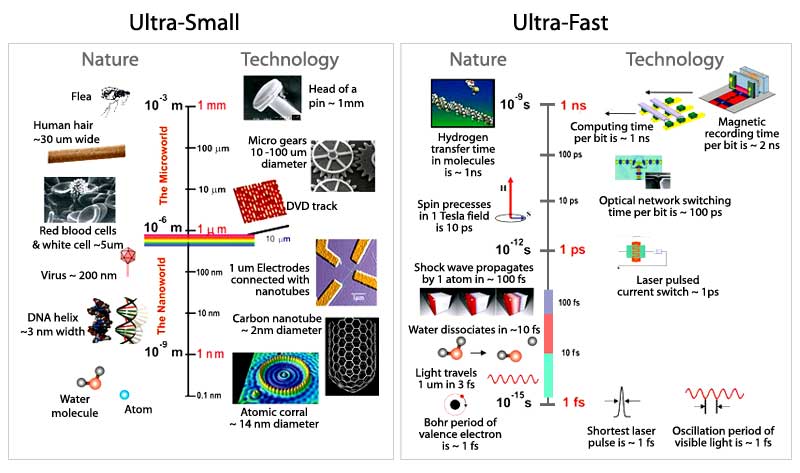

Femtosecond: One femtosecond is 10-15

second. A time this short is impossible to visualize in terms of

everyday experience, but it is a useful unit of time for describing atomic

and molecular dynamics. It takes about 10 femtoseconds for a hydrogen

atom to become attached to or detached from a molecule. Atoms heavier

than hydrogen are more massive and move more slowly, taking a few hundred

femtoseconds to enter or leave a binding site on a molecule. An electron

bound to an atom can transit from one atomic orbital to another in less

than a few femtoseconds. An atom or molecule in a gas or liquid will move

about one angstrom in a few femtoseconds.

Light, which travels at 186,000 miles per second, moves no more than the

thickness of a sheet of paper in 150 femtoseconds.

Light, which travels at 186,000 miles per second, moves no more than the

thickness of a sheet of paper in 150 femtoseconds.

There are about as many femtoseconds in a minute as there are minutes

in the entire history the universe.

There are about as many femtoseconds in a minute as there are minutes

in the entire history the universe.

Source:

Office of Basic Energy Science

Self-Amplified Spontaneous Emission - SASE

An intense, highly collimated electron beam  travels

through an undulator magnet. The alternating north and south poles

of the magnet force the electron beam to travel on an approximately

sinusoidal trajectory, emitting synchrotron radiation travels

through an undulator magnet. The alternating north and south poles

of the magnet force the electron beam to travel on an approximately

sinusoidal trajectory, emitting synchrotron radiation  as

it goes. as

it goes. |

|

The electron beam and this synchrotron radiation travelling with it

are so intense that the electron motion is modified by the electromagnetic

fields of its own emitted synchrotron light. Under the influence of

both the undulator and its own synchrotron radiation, the electron

beam begins to form micro-bunches,  separated

by a distance equal to the wavelength of the emitted radiation. separated

by a distance equal to the wavelength of the emitted radiation. |

|

These micro-bunches begin to radiate as if they were single particles

with immense charge. The process reaches saturation when the micro-bunching

has gone as far as it can go. |

|

|

Glossary

Glossary Glossary

Glossary