Semicrystalline polymers, such as polythiophenes, hold much promise as active

layers in printable electronic devices such as photovoltaic cells, sensors, and

thin film transistors. As organic semiconductors approach commercialization,

there is a need to better understand the relationship between charge transport

and microstructure, in particular, to identify the inherent bottlenecks to

charge transport. In semicrystalline and polycrystalline materials, charge

transport is most likely dominated by grain-boundary effects, although the

exact mechanism is not well understood. Unfortunately, grain boundaries in

semicrystalline thin films are difficult to characterize: the grains are too

small to allow for measurements across individual grain boundaries (as is often

done for polycrystalline films of small molecules) and bulk measurements are

complicated by the unknown orientation of polymer chains within the grain. To

better understand the effect of chain orientation on grain boundaries, we use

anisotropic thin films of poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) - one of the most

well-studied polymeric semiconductors, as a tool to study charge transport.

We characterized the film microstructure and made thin film transistors with

the anisotropic film as the active layer. This allowed us to quantitatively

extract the effect of different grain boundary structures on charge transport

and showed for certain low-angle grain boundaries, charge transport is due to

bridging polymer molecules. Our study shows that optimization of the

microstructure in semicrystalline electronic devices should include efforts to

control grain boundary structure and orientation.

From our diffraction experiments, we were able to develop a model of the film

microstructure, shown in Figure 1, right. By collecting diffraction data from

only the crystalline regions, we have obtained indirect information about the

structure at the grain boundaries. It has been previously suggested that in

polymeric semiconductor films, grain boundaries separating two grains with a

small orientation mismatch, known as "low-angle" grain boundaries, can contain

bridging polymer chains that create favorable paths for intergrain charge

transport. Our films are comprised entirely of low-angle boundaries, but due to

the orientation of the polymer axis, boundaries along the fibers, or "in-line"

boundaries, are more likely to have bridging polymer chains than boundaries

between fibers. To test the effect of these boundaries on charge transport, we

made thin film transistors (TFTs) using the anisotropic film in two different

orientations, one with fibers parallel to the channel length along which the

current flows (parallel devices) and the other with fibers perpendicular to the

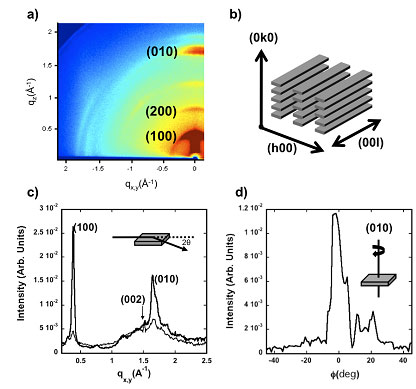

channel length (perpendicular devices.) The mobility values for the two types

of devices revealed a significant mobility anisotropy: parallel devices had

mobilities approximately 20 times higher than perpendicular devices (Figure 3).

In fine-grained materials such as the directionally crystallized films of P3HT,

the effective device mobility is dominated by the mobility in the grain

boundaries. Thus, the mobility anisotropy in the semicrystalline films studied

here is attributed to different microstructure at the grain boundaries.

Transport across grain boundaries along the fiber, with the potential for

bridging polymer chains, is easier than transport across the fibers.

Additionally, similar activation energies, extracted from temperature dependent

mobility measurements (Figure 3, inset), indicate that despite mobility

anisotropy, charge transport in the two types of devices is governed by the

same transport bottleneck. We believe that due to film imperfections, grain

boundaries between fibers play a role in both types of devices, serving as the

rate limiting step.

In summary, we have created anisotropic films of P3HT via directional

crystallization and used them as a tool to study the effect of grain boundary

structure on charge transport. Film microstructure was largely characterized

using X-ray diffraction at SSRL, and charge transport was investigated by

making thin film transistors with the anisotropic films as the active layer.

This work helps to solidify the hypothesis that in low-angle grain boundaries,

transport is easier only in the direction parallel to the polymer backbone, due

to bridging polymer molecules. Optimization of the microstructure in electronic

devices should therefore not focus solely on the elimination of grain

boundaries, but also include efforts to control grain boundary placement and

relative grain orientation.

"Charge Transport Anisotropy Due to Grain Boundaries in Directionally

Crystallized Thin Films of Regio-Regular Poly(3-hexylthiophene)", L.H. Jimison,

M.F. Toney, I. McCulloch, M. Heeney, A. Salleo. Adv. Mater. 21,

1568-1572 (2009).

Primary Citations

"Orientation of Regioregular Poly(3-hexylthiophene) by Directional

Solidification: A Simple Method to Reveal the Semicrystalline Structure of a

Conjugated Polymer" M. Brinkmann, J. Wittmann. Adv. Mater.

18, 860 (2006).

"Transport in polycrystalline polymer thin-film transistors" R. Street, J.

Northrup, A. Salleo. Phys. Rev. B. 71, 13 (2005).

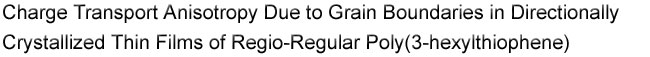

Anisotropic thin films of P3HT are fabricated by a directional crystallization

technique adapted from Brinkmann and Wittmann (see reference for fabrication

details). The behavior of the films under polarized light suggests widespread

alignment of the polymer chains, with the chain axes parallel to the fiber

axis. Atomic Force microscopy reveals areas of continuous, aligned films, and

suggests the presence of grains along the fibers (Figure 1, left). X-ray

diffraction experiments at SSRL Beam Lines 11-3 and 7-2 were used to

characterize the semicrystalline microstructure of the anisotropic films more

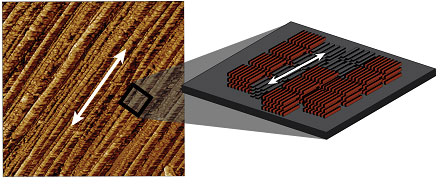

directly. Two-dimensional grazing incidence X-ray scattering (2D GIXS) survey

patterns (Figure 2a) reveal the unique texture of these P3HT films. Typical

Figure 1:

Phase mode AFM image of directionally crystallized P3HT, revealing the unique

grain structure. The white arrow indicates the direction of the fiber axis and

polymer chain axis. The scan is 4 by 4 mm. (Left) The cartoon shows a possible

orientation of crystallites within the directionally crystallized film, as

derived from XRD. Red crystallites are "edge-on" with their pi-pi stacking

repeat in the plane of the substrate. Grey crystallites are termed "face-on,"

with their pi-pi stacking repeat out of the plane of the substrate. In this

cartoon of the grains, the longest axis is long the polymer chain backbone

(001), the next longest along the alkyl-stacking direction (100) and the

shortest along the pi-pi stacking direction (010), see Figure 2b for reference.

(Right)

spin-cast thin films of P3HT are highly textured out of plane, with the

alkyl-stacking repeat direction lying out of the plane of the substrate and the

resulting (h00) peaks appearing along the qz axis. In the

directionally crystallized films, the peak corresponding to the pi-pi stacking

appears out-of-plane, along with weaker (h00) peaks (see Figure 2b for

reference). The presence of both of these Bragg peaks along the

qz axis

indicates that there is a distribution of crystallites present in our films,

"face-on" and "edge-on," as shown in the right hand side of Figure 1.

High-resolution GIXS experiments were performed at two different substrate

orientations, probing repeat distances both along the fibers and across the

fibers. The difference in these diffraction patterns confirms significant

in-plane crystalline anisotropy. The Bragg peaks that are present in the GIXS

patterns also confirm the orientation of the chain axis along the fiber axis,

and two different crystallite orientations, as suggested above.

Figure 2:

a) Grazing Incidence X-Ray Diffraction (GIXD) survey pattern of directionally

crystallized P3HT, revealing the unique thin film texture. b) A representative

crystallite of P3HT, for reference. c) High resolution grazing incidence X-ray

diffraction, taken in two different sample orientations (phi). The thick black

line corresponds to a scattering vector oriented across the fibers. The thin

black line corresponds to a scattering vector oriented along the fibers. d) A

phi scan of the (010) peak, quantifying in-plane film anisotropy.

Figure 3:

Temperature dependent mobilities for perpendicular (black) and parallel (grey)

devices. The different symbols correspond to different devices. Inset:

Activation energies extracted from the temperature dependent mobilities. Error

bars for the parallel devices are smaller than the symbols.

Further Reading

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.