Carbon-based materials have long been used for a variety of water purification

operations. Researchers have investigated carbon materials as adsorbents for

decades, but only limited information on the precise details of aqueous ion

interactions with carbon surfaces has been uncovered. It is empirically known

that the affinity of activated carbon for various hydrated ions depends

critically on how the material is processed. Processing influences the types of

chemical groups and the structure of the carbon surface, which in turn

influences the strength of interaction between hydrated ions and the carbon

surface. It is also believed that many of the puzzling properties of

impurity-free carbon, such as ferromagnetism, are governed by specific

modifications of the carbon surface. However, very little is known about the

local structure of the carbon surface that is responsible for its aqueous ion

affinity.

In a recent paper published in Advanced Materials, former Lawrence Livermore

National Laboratory scientist Jason Holt, along with SSRL scientists Apurva

Mehta, Erik Nelson, and Samuel Webb have found that both activated carbon and

carbon nanotubes share a common surface site that binds bromide ions present in

solution, and by implication other aqueous halides as well. These sites have a

significant impact on the chemical properties of these materials and provide a

picture of carbon surface chemistry that is consistent with the proposal of a

recent theoretical study.[1]

To probe the details of ion structure, a technique was needed that is sensitive

to the local environment around ions that may be trace in abundance in samples.

The technique of extended x-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) is ideally

suited for this purpose, and beamlines 10-2 and 7-3 at the Stanford Synchrotron

Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) were used to carry out these measurements. Carbon

materials were prepared for these measurements by taking them in powdered form

and treating them with a concentration solution of rubidium bromide, followed

by a series of washing cycles to remove excess ions present in the bulk

solution.

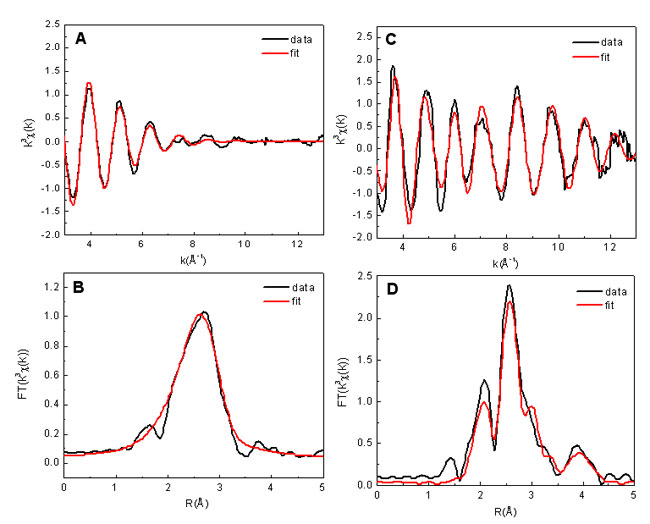

Figure 1 shows the bromine EXAFS oscillations, k3C(k), for both a bulk

solution

sample (0.5M rubidium bromide) and an activated carbon sample (AC6), their

pseudoradial distribution functions (R-function), as well the best model fits

for k3C(k) and the

R-functions. The k-space EXAFS of the bulk solution dies out

rapidly by k~10Å-1, indicating significant disorder in the outer coordination

shells. This suggests that the interaction of the Br with more distant water

molecules is very weak (and probably strongly screened by the first

coordination shell). In contrast, the EXAFS of the activated carbon sample

shows a beating of several frequencies and extends out beyond

k=13Å-1,

indicating that Br binds to a very ordered structure in a very specific manner.

The resulting R function is also much more complex, with multiple peaks

observed, suggesting that the local structure around a Br ion in the activated

carbon sample is dramatically different from that in aqueous solution. Similar

results were seen with single wall carbon nanotube samples that were analyzed.

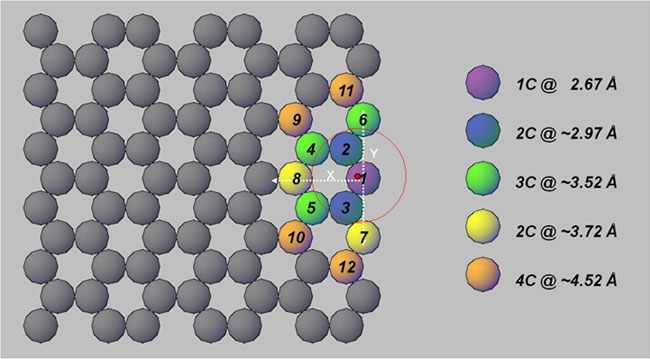

Because several close and partially overlapping scattering shells were visible

in the experimental EXAFS data, due to Br attachment to the graphitic material,

fitting consisted of creating a rigid graphitic sheet and refining the position

of Br over this sheet. There are two general types of locations available for

an adsorbate on a graphitic sheet. The first places the Br ion in the middle of

a complete graphitic sheet, either towards the broad end of the carbon ring or

nearer to the triangular portion of the carbon ring. The second general

location for an adsorbate is at the edge of the sheet. The first type of edge

site corresponds either to the concave or the convex portion of the broad part

of a "broken" carbon ring that has a 4 carbon periodicity (the "armchair"

site). The second edge location corresponds to the concave or convex corner of

the triangular part of the "broken" carbon ring. Such an edge has a 2 carbon

periodicity and is referred to as a "zigzag site". After considering all

candidate locations and examining their fit statistics, it was concluded that

the bromine ion does not attach to the middle of the graphitic sheet but to an

edge site, with a strong preference for a convex, zigzag edge, as illustrated

schematically in Figure 2. Note that in addition to actual edges of graphitic

sheets, these edge sites can be in the middle of a graphitic sheet, or on the

side of a carbon nanotube, provided the sheet or tube is punctured (i.e.,

vacancies are present). A recent theoretical study [1] proposes an oxygen-free

basic site, the carbene site at graphene zigzag edges that appears consistent

with the experimental results reported here. These sites can be protonated in

aqueous solution, producing a positively charged carbon with which anions may

interact through ion pairing.

In conclusion, the present results provide the first structural picture of the

location and binding geometry of aqueous halogen ions to a graphitic sheet.

The results also suggest how the presence of zigzag graphitic edge sites can

alter the ion affinity. These particular sites may prove important for

proposed uses of carbon nanotube membranes [2] for desalination, as well as

carbide-derived carbons for electrolytic supercapacitors.[3]

Primary Citation:

References:

Figure 1.

Bromine EXAFS signal (A) and the R-function (B) for the 0.5M rubidium bromide

reference solution. Corresponding bromine EXAFS (C) and R-function (D) for the

activated carbon sample, along with model fits (in red) derived from FEFF8.[3]

The fit was performed over a k-space from 3 to 12.7 Å-1

(R from 1 to 4.7 Å) for

the solution sample and the AC6 sample. The difference between the peak

positions and the true Br coordination distances can be resolved by a phase

correction term.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the structural model for Br coordination to graphene materials,

derived from a model fit of the activated carbon EXAFS data. Bromine sits atop

a convex zigzag site on the edge of the graphene sheet (red dot above carbon

atom #1). The Br position relative to the axes is x = 0.199±0.040Å, y =

0.076±0.029, z = 2.658±0.008, where z is the direction above the graphitic

sheet.

A. Mehta, E.J. Nelson, S.M. Webb, and J.K. Holt, Adv. Mat.,

published online 10/30/08; DOI: 10.1002/adma.20080160

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.