|

|

| Fig. 1. Rapid-scanning x-ray fluorescence mapping ex perimental setup. Synchrotron x-rays at 11 keV passed through a 50 Ám aperture (Ap). The beam intensity was monitored with a N2-filled ion chamber (I0). The brain slice was mounted vertically on a motorized stage (St) at 45° to the incident x-ray beam and raster scanned in the beam. A 13-element Ge detector (Ge) was positioned at a 90° angle to the beam. |

In an article published in the March 24 issue of Cerebellum, Popescu and

co-workers have provided new insight into which brain metals are dysregulated

in spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA). SCAs are a group of degenerative disorders

that affect the cerebellum, the spinal cord and the connections between them

causing a type of uncoordinated movement called ataxia. Friedreich's ataxia,

ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency, X-linked sideroblastic anemia with

ataxia, ataxia telangiectasia and infantile-onset spinocerebellar ataxia are

examples of SCAs that have been linked to metal abnormalities. Each of these

conditions has a different cause and thus, each may have a different pattern of

metal dysregulation.

Rapid scanning X-ray fluorescence imaging [5], conducted on

SSRL Beam Line 10-2, was used to compare the normal distribution of iron,

copper and zinc to their distribution in a case of SCA. Formalin-fixed slices

of brain and spinal cord, approximately 1 cm thick, were purchased from the

Brain and Tissue Bank

for Developmental Disorders at the University of Maryland, a facility funded by

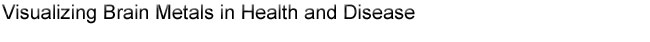

In the SCA sample, the forebrain did not show degenerative changes but the

distribution of metals was unusual (Fig. 2). The basal ganglia are huge brain

nuclear masses that integrate and regulate the excitatory and inhibitory

circuitry adjusting the movement, amongst other functions. The globus pallidus

par externa (GPe) is part of the basal ganglia involved in movement inhibition.

The GPe of the SCA brain had about 80% more iron than the GPe of the normal

brain. The importance of GPe iron in the development or potential treatment of

SCA remains to be determined since no obvious cellular degeneration was seen in

the GPe.

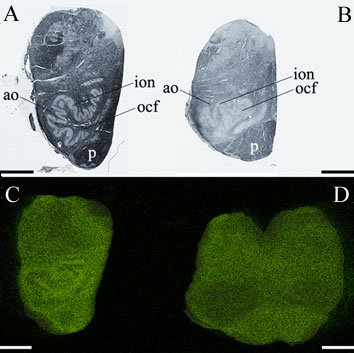

The cerebellum (Fig. 4) is quite rich in metals and contains one of the most

metal-rich structures in the brain, the dentate nucleus [7].

The striking branching pattern of the cerebellar white matter called the

arbor vitae (tree of life) is clearly distinguished on the basis of its

metal content. In SCA the iron content of the dentate nucleus is much lower

than that seen in the control brain, and the arbor vitae is not as

prominent.

The high metal content of the dentate nucleus, white matter of the cerebellum

and the medullary 'olive' makes these brain regions particularly susceptible to

metal-catalyzed oxidative damage, neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration should

metal metabolism become dysregulated. This study shows that neurodegeneration

Beam line 10-2 has recently been upgraded with a new set of motorized stages

which allow rapid collection of x-ray fluorescence data on large samples (up to

300 mm x 600 mm) and new fluorescence x-ray digital signal processors. This

new data collection system also allows rapid collection of data points, the

collection of the full x-ray fluorescence spectrum at every pixel, and the

ability to return to points of interest easily to further collect x-ray

absorption spectra. These and other upgrades in the future will be utilized

for further studies on SCAs and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Primary Citation

Popescu, B., F., Gh, Robinson, C.A., Chapman, L.D., Nichol, H. (2009)

Synchrotron X-ray Fluorescence Reveals Abnormal Metal Distributions in the

Brain and Spinal Cord in Spinocerebellar Ataxia: A Case Report.

Cerebellum, Mar

24 (Epub ahead of print) DOI 10.1007/s12311-009-0102-z.

the National Institute of Child Health and Development. The brain and spinal

cord slices were sealed without further treatment under metal-free plastic or

Mylar and raster-scanned in the beam (Fig. 1). Areas of interest were

subsequently excised for histological and immunohistochemical analysis.

Fig. 2.

Metals are increased in the globus pallidus pars externa; A. Gross section of

the control forebrain; B. Gross section of the SCA forebrain; C. Overlay of Fe

(red), Cu (green) and Zn (blue) distribution of the control forebrain; D.

Overlay of Fe (red), Cu (green) and Zn (blue) distribution of the SCA

forebrain; c caudate; p putamen; gpe globus pallidus pars externa; ic internal

capsule; ac anterior commissure; arrows blood vessels; arrowheads metal rich

white matter regions; scale bar=5 mm.

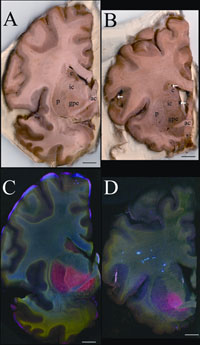

The brainstem connects the forebrain to the spinal cord. In the part of the

brainstem called the medulla is an important movement coordination center named

after its shape "the olive". Popescu et al. found that the nerve cell

processes that pass from this region to the cerebellum are exceptionally rich

in copper and this had not been previously described (Fig. 3). In contrast to

the normal medulla, the 'olive' of the SCA medulla was nearly devoid of copper.

It is not known why these fibers are normally rich in copper but they lack

copper in SCA. However, it is interesting to note that intoxication with

clioquinol, an antibiotic and potent copper chelator, causes characteristic

degeneration in this brain region [6].

Fig. 3.

Cu is abundant in the control olive and decreased in the degenerated olive of

the SCA patient; A Normal histological appearance of the control medulla (Luxol

fast blue/cresyl violet staining); B Degenerated olive in the SCA medulla

(Luxol fast blue/cresyl violet staining); C. Cu map of the control medulla; D.

Cu map of the SCA medulla; ion inferior olivary nucleus; ocf olivocerebellar

fibers; ao amiculum olivae; p pyramids; scale bar=5 mm.

can be linked to either metal accumulation or reduction depending upon the

brain region and the stage of neurodegeneration. The ability to map multiple

metals in whole human brain gives us a new tool to examine metal pathologies in

a variety of diseases affecting the brain and spinal cord.

Fig. 4.

Iron is decreased in the degenerated dentate nucleus and metals are decreased

in the cerebellar white matter of the SCA patient; A Gross section of the

control cerebellum; B Gross section of the SCA cerebellum; C. Overlay of Fe

(red), Cu (green) and Zn (blue) distribution of the control cerebellum; D.

Overlay of Fe (red), Cu (green) and Zn (blue) distribution of the SCAl

cerebellum; dn dentate nucleus; wm white matter; gm cortical gray matter; scale

bar=5 mm.

References

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.