Starting in the 1970s, federal regulatory control and eventual elimination of

lead-based "anti-knock" additives in gasoline decreased the level of airborne

Pb in the USA by two orders-of-magnitude [1]. Blood lead levels

of the USA

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. The good, the bad, and the ugly.

Ambient airborne particulate matter captured on filters of woven silica fiber

(large strips) and TeflonTM (round). Clean fiber filter at bottom

for comparison. Take a deep breath?

|

|

population decreased correspondingly [2,3].

Despite this dramatic improvement in both exposure risk and body burden of Pb,

the sources and health threat of the low levels of lead in our "unleaded" air

remain topics of scientific and public health interest [4,

5]. Lead is a potent

neurotoxin in children, particularly for toddlers whose brains are developing

and who often are exposed to lead through hand-to-mouth transfer. Some

researchers posit that there is no safe minimum exposure.

Societal decisions on regulation of airborne lead involve not just medical

knowledge, but also an understanding of the sources of airborne lead, the

cycling of lead in urban settings, and human exposure routes. Mobile

(vehicular) sources represented the dominant Pb input through much of the

20th Century. With the elimination of leaded gasoline, focus in

developing a new air standard for Pb has been on such point sources as

smelters, lead recycling operations, manufacturing, combustion, and the

continued use of leaded fuel for aviation piston engines [6].

Late last year the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) unveiled their new

airborne particulate standard for lead, 0.15 mg Pb

m-3 air, averaged over rolling 3-calendar-month periods [6-8]. This is an order-of-magnitude decrease

from their 1970s-era standard of 1.5 mg Pb

m-3 air.

In spite of this progress, it was reported that other researchers and even some

members of the EPA's scientific advisory panel urged stricter limits, as low as

0.02 mg Pb m-3 air

[8,9].

Instead of considering potential sources of airborne lead, a multi-disciplinary

team of environmental and health scientists from the University of Texas at El

Paso posed the question: what species (compounds) of Pb are actually

present in our air? Their approach, using x-ray absorption spectroscopy, was to

identify and, if possible, quantify the major species Pb in ambient airborne

particulate matter collected in El Paso, TX, USA. The diverse team included a

geochemist, a nurse, an engineer, an environmental sciences graduate student,

and a retired air-quality manager.

The team examined 20 samples of particulate matter (PM) collected on woven

silica fiber filters in 2005 and 1999 at three sites in El Paso. The XAS

experiments, conducted on Beam Lines 7-3, 10-2, and 11-2 at SSRL, proved

challenging: the amount of Pb that was exposed to the beam was in the

nanogram-to-microgram range. Nonetheless, it became clear that the PM samples

exhibited the same overall XAFS (x-ray absorption fine structure) structure.

That "fingerprint" also proved similar to those of soil samples collected

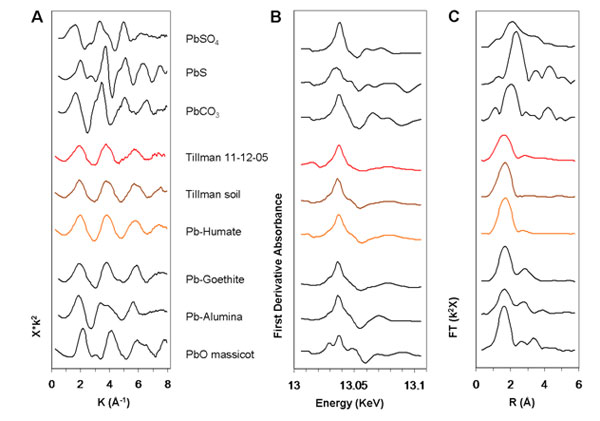

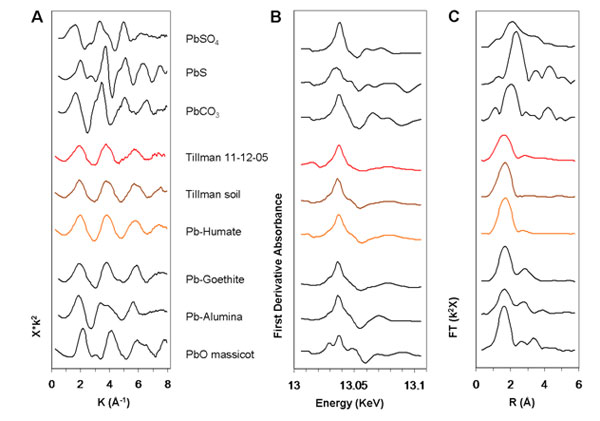

nearby (Fig. 2). Comparison of the PM spectral fingerprint to those of common

forms of environmental Pb turned up one prime suspect, Pb-humate (Fig. 3). Lead

humate is a stable complex of Pb sorbed to humic acid; it forms exclusively in

the humus fraction of soils. In Pb-humate, near-neighbor shells to the sorbed

Pb are populated by O and C atoms; the lack of strong backscatterers (e.g., Pb,

as in crystalline, space-repetitive Pb salts) in farther shells yields a simple

spectrum and Fourier transform.

| |

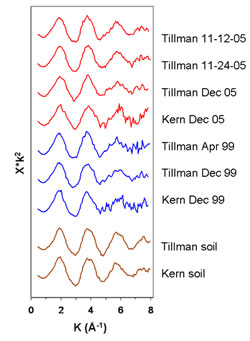

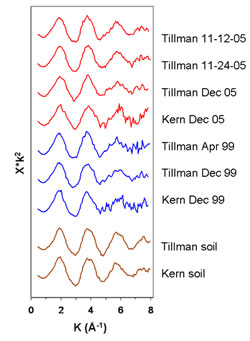

Figure 2. Pb-LIII XAFS spectra of PM samples and associated

local soils. Spectra are background-subtracted, normalized,

k2-weighted, and plotted in k-space. Because the

small amounts of Pb in the PM produced noisy XAFS, multiple abbreviated scans

were stacked. Since we sampled only a short region of k-space, the

XANES and EXAFS regions are presented together as a single XAFS fingerprint.

Tillman and Kern are old neighborhoods in the urban core of El Paso with

long-term PM collection stations. (Figure adapted from Pingitore et al. 2009)

|

|

|  |

|

Figure 3: Pb-LIII XAFS and derived spectra of model compounds,

PM, and

soil. (A) XAFS spectra. Spectra are background-subtracted, normalized,

k2-weighted, and plotted in k-space.

(B) Derivatives of Pb-LIII XANES spectra

of several samples and model compounds. Derivatives were taken of spectra that

had been background-subtracted, normalized, and k2-weighted.

(C) Radial

distribution functions (RDF) derived from Fourier transforms of

Pb-LIII XAFS

spectra of samples and model compounds. No distance correction for the phase

shift during photo-electron backscattering was applied. (Figure adapted from

Pingitore et al. 2009) |

|

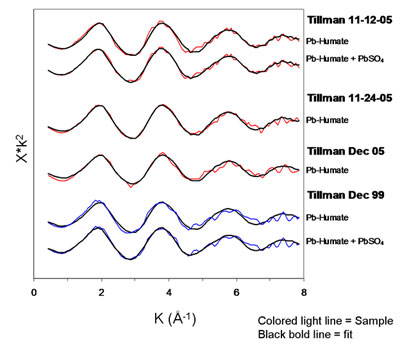

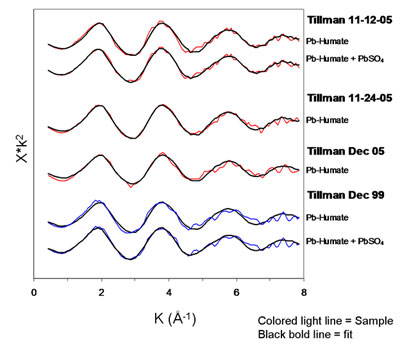

Least-squares fits of Pb-humate to the El Paso PM are striking (Fig. 4). In

some samples a small amount of lead sulfate may also be present. Lead humate

also provided near perfect fits to the local soil samples. Despite these

compelling fits, it is possible that sorption complexes on other

low-atomic-number materials (e.g., some clays) could provide computationally

equivalent matches and be present in the PM. This would not, of course, have

bearing on the match observed between PM and soil.

|  |

|

|

Figure 4. Least-squares fits of XAFS spectra of PM with Pb-humate and

Pb-humate + PbSO4. The contribution of PbSO4 to the

fit in 2 cases was ~ 15%. In the other two cases the lead sulfate did not

improve the fit noticeably and was omitted. (Figure adapted from Pingitore et

al. 2009) |

|

The study concluded that local Pb-contaminated soils, father than current

industrial emissions, are the dominant source of Pb in contemporary airborne

particulate matter in El Paso, TX. This provides direct evidence for an earlier

suggestion that soil lead might explain the large discrepancy in mass-balance

input-outflow models of Pb in the Los Angeles air basin [7].

Thus, earlier anthropogenic Pb releases left a legacy of contaminated soils

that now leak Pb into our air in a perverse form of recycling. The process will

continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

From a health standpoint, the typical US inhabitant actually takes in very

little Pb by simply breathing, compared to such other activities as eating. The

real risk of airborne Pb is for toddlers, crawling on floors contaminated with

lead-bearing dust, the indoor fallout from resuspended Pb-contaminated soil.

The bottom line? At some point, meeting further legislative restriction of Pb

in airborne particulate matter could require the remediation or removal of

Pb-contaminated soil to prevent its resuspension into the air. That will prove

very expensive. And for those toddlers, worth it.

Primary Citation

Pingitore Jr NE, Clague J, Amaya MA, Maciejewska B, Reynoso JJ (2009) Urban

Airborne Lead: X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Establishes Soil as Dominant

Source. PLoS One 4(4): e5019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005019

http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0005019.

References

[1] Davidson CI, Rabinowitz M (1992) Lead in the environment: From sources

to human receptors. In: Needleman HL, editor. Human Lead Exposure. Boca Raton:

CRC, pp. 65-86.

[2] Annest J, Dirkle J, Makuc C, Nesse J, Bayse D, et al. (1983)

Chronological trend in blood lead levels between 1976 and 1980. N Engl J Med

308: 1373-1377.

[3] ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry) (1988) The Nature

and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United States: A Report to

Congress. Atlanta: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service,

ATSDR.

[4] Anon (2007) Tougher standard for lead in air recommended. Chem Eng News

85(46): 39.

[5] Stokstad E (2008) Panel: EPA proposal for air pollution short on

science. Science 319: 146.

[6] US Environmental Protection Agency (2008c) Environmental Protection

Agency 40 CFR Parts 50, 51, 53 and 58 [EPA-HQ-OAR-2006-0735; FRL-_____- _] RIN

2060-AN83 National Ambient Air Quality Standards for Lead. Available:

http://epa.gov/air/lead/pdfs/20081015_pb_naaqs_final.pdf [accessed 7 November

2008].

[7] Harris AR, Davidson CI (2005) The role of resuspended soil in lead

flows in the California South Coast Air Basin. Environ Sci Technol 39:

7410-7415.

|