|

|

|

|

|

|

Core level spectroscopies are a group of different techniques to obtain element-specific information of the electronic structure around an absorption site and are thereby suitable tools to study the chemical state, local geometric structure, nature of chemical bonding, and dynamics in electron transfer processes centered around one atomic site. Core hole formation

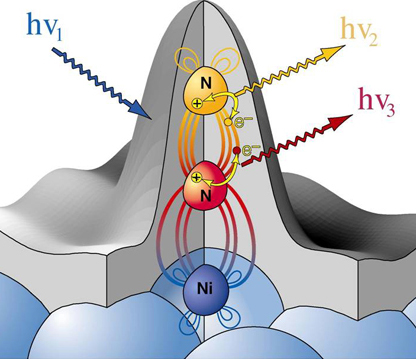

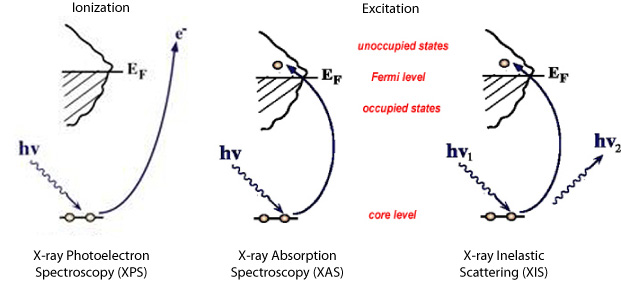

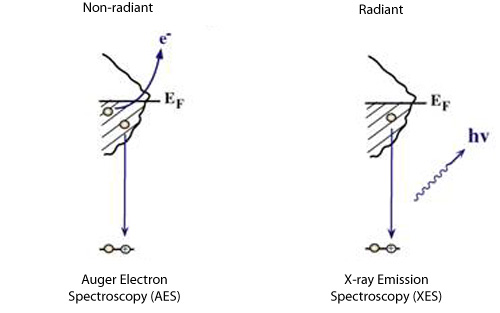

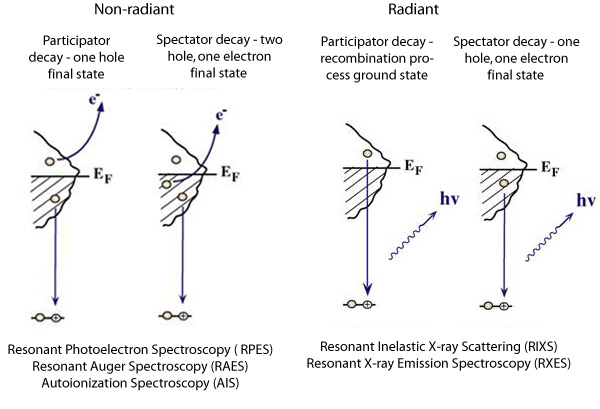

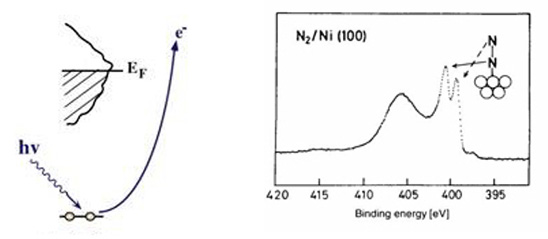

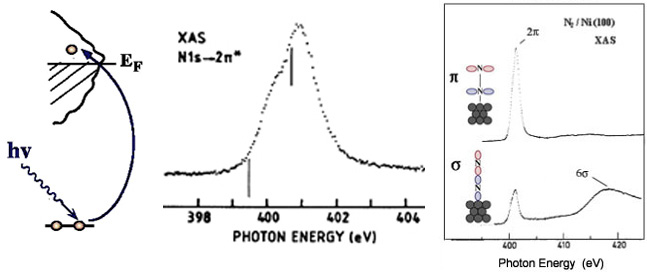

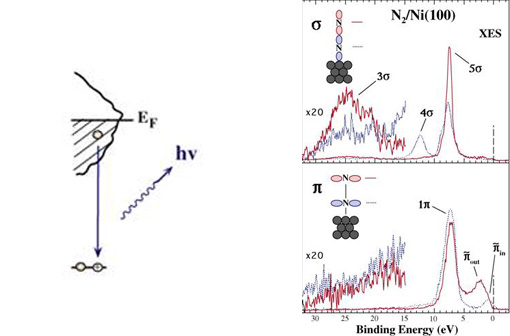

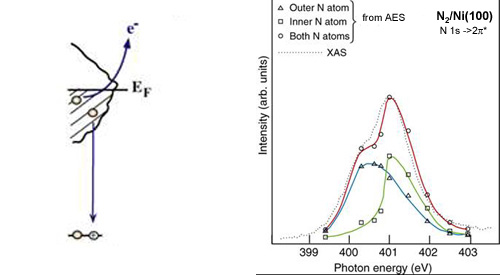

We can create a core-hole through the absorption of incoming light with energy matched to the binding energy of a core electron. This absoprtion causes the core electron to be excited to a bound state or to the continuum where it will become a free particle. The creation of a core hole by ionization forms the basis for XPS while the creation of a core hole by excitation is studied in XAS. After ionization the atom is in a highly excited state due to the creation of the core hole. The atom relaxes via a radiant or a non-radiant process. The radiant decay of the core holes forms the basis for XES while non-radiant decay is studied in AES, both of which provide tools for probing ocuppied electronic structure of a model system. These events only consider a core-ionized initial state prior to the decay. However, an initial state with the core electron instead excited into a bound state can modify the decay process. The two steps, creation and decay, can lead to coupling and the whole process can be considered a one step event. These events are called resonant processes and can involve radiant and non-radiant decays. The excited electron can either participate in the decay process or be passive as a spectator leading to very different types of final states as shown below. Creation of Core Holes  Decay of Core Holes  Resonant Processes  X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)  In XPS photons with sufficient energy are absorbed by a system causing core electrons to be ejected from the sample. If the energy of the photons is larger than the binding energy of the electron, the excess energy is converted to kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectron. Knowledge of the incoming photon energy and the work function of the spectrometer and measurement of the kinetic energy via an electron analyzer makes it possible to calculate the binding energy according to: electron binding energy = photon energy - kinetic energy of the emitted electron - workfunction. Since binding energies of core electrons are characteristic for elements in a certain chemical environment, XPS allows for a determination of the atomic compositions of a sample or the chemical state of a certain element as well as electronic structure and band structure. In many cases chemical shifts can be used to draw direct conclusions on the local coordination in a system and the electronic change upon adsorption. This information can be used to distinguish different adsorption sites of molecules adsorbed on a surface as shown above right in the XPS spectrum for N2 perpendicularly adsorbed on a Ni(100) surface. Here two well-separated N 1s peaks are observed with a chemical shift of 1.3 eV. The peak with the lowest binding energy, 399.4 eV, corresponds to ionization of the outer N atom, whereas the high binding energy peak at 400.7 eV is due to ionization of the inner N atom.  The figure at the center above is a enlarged view of the ?-bonding network obtained with XAS. The total intensity of the spectrum is given by the number of unoccupied states in the inital state, while the spectral shape reflects the density of states for the final state. In this way XAS provides element-specific information about the density of states, local atomic structure, lattice parameters, molecular orientation, the nature, orientation, and length of chemical bonds as well as the chemical state of the sample. Due to the localization of the core hole created at a certain atom, the unoccupied states are projected on this atom. In the soft x-ray regime (K-edges of C, N, O), NEXAFS transitions are governed by dipole selection rules and consequently the absorption cross-sections show a polarization dependent angular anisotropy. By means of polarization dependent NEXAFS measurements it is therefore possible to determine the orientation of molecular adsorbates. Molecular orientation for N2 adsorbed on Ni (100) obtained using NEXAFS is illustrated above right. In systems with inequivalent atoms of the same element, the XAS spectrum can become complicated due to overlapping spectral features. The energy separations between these features are usually small and the shape and intensity of the spectral components may vary significantly, precluding a straightforward separation. However, with the help of Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), an XAS spectrum can be decomposed into its individual components.  In the case of highly oriented systems, e.g. the case of N2 standing up on Ni(100) shown above, angular- dependent XES enables the separation of states of different symmetry of the involved orbitals. An important consequence is that one can study states of symmetry which result solely from the chemical bonding. The maximum x-ray emission is generally found in the direction perpendicular to the spatial orientation of the involved atomic ?-orbitals. By switching the direction of detection from normal to grazing emission, orbitals of different spatial orientation are probed. In normal emission geometry, only valence states of ?-symmetry contribute to the x-ray emission signal, whereas in grazing emission geometry both ?- and sigma-orbitals are probed. A simple subtraction procedure reveals sigma states only.  In general, since the initial ionization is non-selective and the initial hole may therefore be in various shells, there will be many possible Auger transitions for a given element - some weak and some strong in intensity. Auger Spectroscopy is based upon the measurement of the kinetic energies of the emitted electrons which are independent of the mechanism of initial core hole formation. Each element in a sample will give rise to a characteristic spectrum of peaks at various kinetic energies. An example can be found above in the case of N2 adsorbed on Ni(100), where we see separation of the N 1s XAS 2p resonance for N2/Ni(100) into absorption peaks from the inner and outer atoms, respectively. In this way AES allows not only for a quantitative compositional analysis of the surface of interest, but provides a tool to separate the two XAS features for the two inequivalent N2 atoms in more detail. Since the shapes and intensities of these subspectra are not a priori known this information can not be obtained from a direct analysis of the absorption spectra. |