Matthew

Ginder-Vogel1, Wei-Min Wu1, Jack Carley2,

Phillip Jardine2, Scott Fendorf1 and Craig

Criddle1

Matthew

Ginder-Vogel1, Wei-Min Wu1, Jack Carley2,

Phillip Jardine2, Scott Fendorf1 and Craig

Criddle1

1Stanford University, Stanford, CA

2Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN

|  |

|

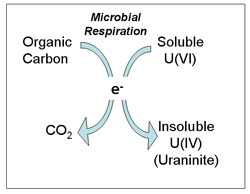

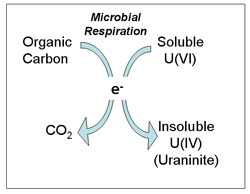

Figure 1. Uranium(VI) reduction is driven by microbial respiration

resulting in the precipitation of uraninite. |

Uranium contamination of ground and surface waters has been detected at

numerous sites throughout the world, including agricultural evaporation ponds

(1), U.S. Department of Energy nuclear weapons

manufacturing areas, and mine tailings sites (2). In

oxygen-containing groundwater, uranium is generally found in the hexavalent

oxidation state (3,4), which is a

relatively soluble chemical form. As U(VI) is transported through groundwater,

it can bond to surfaces of minerals, a process which may retard its transport

(5-8). It has recently been shown, however,

that U(VI) also bonds strongly to the common groundwater species carbonate and

calcium to form stable dissolved ternary complexes, which can effectively

compete with mineral surfaces as "reservoirs" for U(VI) (9).

As a consequence, significant amounts of U(VI) remain in groundwater, thus

maintaining relatively high mobilities for U(VI), a highly undesirable

scenario. Conversely, the tetravalent oxidation state, U(IV), forms sparingly

soluble solids, even in the presence of dissolved carbonate and calcium, and

thus tends to be relatively immobile. Therefore, the oxidation state of

uranium may play an important role in determining its environmental mobility

(10). Numerous common, dissimilatory metal (DMRB) and

sulfate reducing bacteria (SRB), including Shewanella,

Geobacter, and Desulfovibrio species, couple the oxidation of organic matter

and H2 to the reduction of U(VI), resulting in U(IV) and the subsequent

precipitation of uraninite (UO2) (Figure 1) (11-13), a sparingly soluble phase.

The idea of stimulating these biological processes for the purposes of

stabilizing uranium in the subsurface is therefore promising as a basis for U

remediation technologies, and has been investigated extensively at the beaker

scale (14-16). While so-called bench-top

measurements are valuable for quickly identifying promising research

directions, soils and aquifers are too chemically and hydrologically complex to

be realistically simulated in the laboratory. The long-term stability of

biologically reduced uranium will be determined by the complex interplay of

soil and sediment mineralogy, aqueous geochemistry, microbial activity, and

potential U(IV) oxidants. Many of these factors have been studied under

laboratory conditions; however, the impact of these factors on uranium cycling

in natural, subsurface environments is still poorly understood. It is therefore

essential to complement laboratory-based experiments with careful, long-term

feasibility measurements of U(VI) reduction at contaminated field sites.

|  |

|

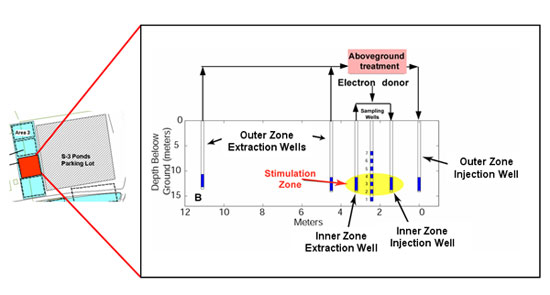

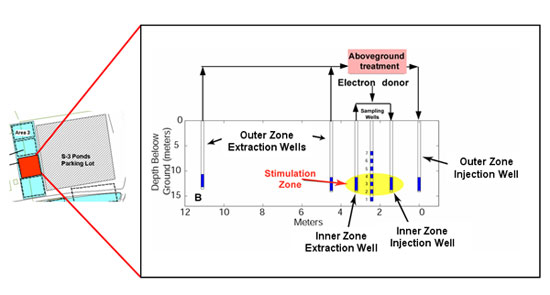

Figure 2. Former S-3 ponds during decommissioning (top), now a parking lot

(bottom). |

Our pilot-scale uranium bioremediation system located at the Y-12 facility

(Area 3) at the Oak Ridge, TN, Field research center (FRC) provides a

controlled subsurface environment in which these factors can be investigated.

Over the course of 31 years, millions of gallons of plating wastes containing

high concentrations of uranium and nitric acid were generated at this location

and discharged into unlined ponds (the S-3 ponds) (Figure 2). In 1983, the

ponds were capped and converted into a parking lot (Figure 2); however, uranium

contamination remains and continues to migrate through subsurface fractures to

surface discharge points. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has established a

Field Research Center (FRC) to assess the potential uranium immobilization

through the stimulation of native populations of DMRB and SRB.

Since 2001, we have been performing uranium bioremediation experiments in FRC

Area 3, immediately adjacent to the former S-3 Ponds (Figure 3). Prior to our

remediation efforts, the uranium concentration (all in the hexavalent state) in

groundwater at Area 3 was ~210 µM and the sediment contained up to 800 mg

U kg-1 sediment, far in excess of the maximum allowable

|  | |

|

Figure 3. Area 3 field site location (left) and well layout (right).

| | | |

concentrations defined by the US EPA. A series of wells were installed at area

3 to control groundwater flow and allow the injection of solutes, such as

ethanol, required to create a geochemical environment conducive for microbial

growth and subsequent U(VI) reduction. The well system consisted of a nested

recirculation system with a protective outer zone to isolate the inner

remediation zone from the ambient geochemical conditions (Figure 3).

Metal-reducing microbial activity in the inner zone was stimulated via ethanol

addition, and dissolved uranium concentrations were monitored in the inner zone

injection and extraction wells, and in a sampling well in the center of the

bioremediation zone (Figure 3). No other such long-term field-scale research

project has been undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of reductive

bioremediation of U(VI) and evaluate how it could be scaled up to treat large

contaminated sites.

|  |

|

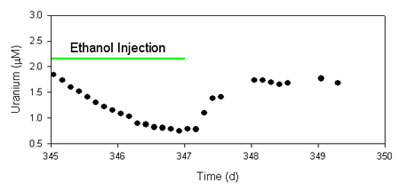

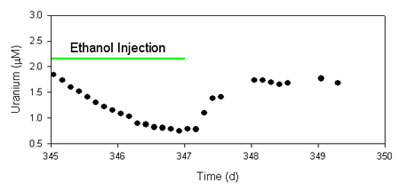

Figure 4. Representative dissolved U(VI) concentrations in a sampling

well during and after ethanol injection. |

| |

After several months of subsurface conditioning to created a low nitrate,

neutral pH remediation zone (14), microbial uranium reduction

was stimulated by injection of ethanol (1.0 - 1.5 mM) through the inner zone

injection well (Figure 3). During the initial uranium remediation period (185 -

535 d of field site operation), dissolved uranium concentrations in the inner

treatment zone decreased rapidly from 2 µM to <1 µM in response to

ethanol addition, exemplified by Figure 4. Ethanol injection was repeated more

than 50 times during this time period and resulted in similar trends in

dissolved uranium concentration.

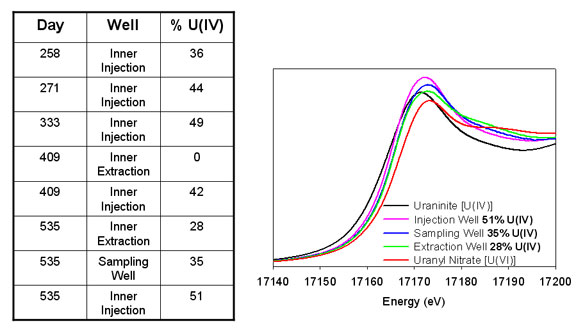

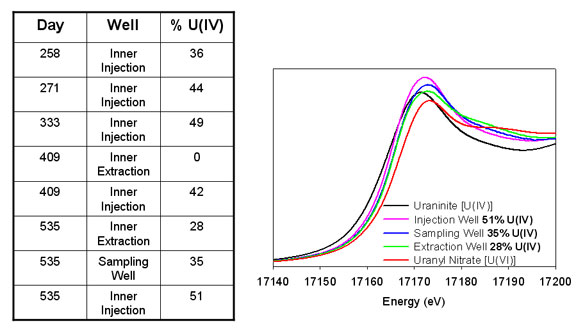

Although bacterial reduction of mobile U(VI) to immobile U(IV) is likely the

mechanism responsible for the decrease in dissolved uranium concentration

during ethanol addition, it is critical to confirm bacterial uranium reduction

by measuring uranium's oxidation state in sediment samples. Sediment samples

from the inner treatment zone wells and a sampling well were analyzed using

X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy at SSRL Beam Line

11-2. Uranium oxidation state in the sediment samples was determined by

comparison of the U LIII-edge XANES spectra of sediment samples to

U(VI) and U(IV) standards (Figure 5) (17). Prior to

biostimulation, U(IV) was not detectable in the subsurface of Area 3. Sediment

samples were retrieved several times during the initial bioremediation period

(Table 1). Partial reduction of U(IV) was first observed in the inner zone

injection well on day 258, and U(IV) continued to accumulate in this well for

the duration of the experiment (Table 1) Initially, U(IV) was not observed in

the inner zone extraction well; however, by day 535, U(IV) was present

throughout the bioremediation zone (Table 1, Figure 5).

|  |

|

Figure 5. Uranium(IV) content of sediment samples during the initial

bioremediation period (left) and uranium LIII-edge XANES spectra from sediment

retrieved on day 535 (right). |

Microbial activity has produced low dissolved uranium concentrations and high

proportions of solid-phase U(IV) throughout the subsurface system remediation

system. Continued biostimulation has resulted in groundwater uranium

concentrations below the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's drinking water

standards (0.126 µM). Current research is examining the long-term

stability of biologically reduced uranium, particularly in the presence of

potential oxidants, including molecular oxygen (18). The

long-term goal of this project is to decrease the flux of uranium leaving the

site to the point that it is harmless.

This work was supported by the US DOE, Office of Biological and Environmental

Remediation Program (ERSP) under grant DOEAC05-00OR22725. Portions of this

research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, a

national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S.

DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Environmental remediation sciences

research at SSRL is supported by the ERSP support program.

Primary Citation

W.-M. Wu, W.-M.; Carley, J.; Gentry, T.; Ginder-Vogel, M. A.; M. Fienen, M.;

Mehlhorn, T.; Yan, H.; Carroll, S.; Pace, M. N.; Nyman, J.; Luo, J.; Gentile,

M. E.; Fields, M. W.; Hickey, R. F.; Gu, B.; Watson, D.; Cirpka, O. A.; Zhou,

J.; Fendorf, S.; Kitanidis, P. K.; Jardine, P. M.; Criddle, C. S. "Pilot-scale

in situ bioremediation of uranium in a highly contaminated aquifer. 2.

Reduction of U (VI) and geochemical control of U(VI) bioavailability", Environ.

Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 3986.

References

-

Bradford, G. R.; Bakhtar, D.; Westcot, D. Uranium, vanadium, and molybdenum in

saline waters of California. Journ. Environ. Qual. 1990, 19, 105-108.

-

Riley, R. G.; Zachara, J. M.; Wobber, F. J. "Chemical contaminants on DOE lands

and selection of contaminant mixtures for subsurface science research," U.S.

Department of Energy, 1992.

- Langmuir, D. Uranium solution-mineral equilibria at low temperature

with applications to sedimentary ore deposits. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta

1978, 42, 547-569.

- Sandino, A.; Bruno, J. The solubility of

(UO2)3(PO4)2·4H2O(s) and

the formation of U(VI) phospate complexes: Their influence in uranium

speciation in natural waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1992, 56, 4135-4145.

-

Moyes, L. N.; Parkman, R. H.; Charnock, J. M.; Vaughan, D. J.; Livens, F. R.;

Hughes, C. R.; Braithwaite, A. Uranium uptake from aqueous solution by

interaction with goethite, lepidocrocite, muscovite, and mackinawite: An x-ray

absorption spectroscopy study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 1062-1068.

-

Bostick, B. B.; Fendorf, S.; Barnett, M. O.; Jardine, P. M.; Brooks, S. C.

Uranyl surface complexes formed on subsurface media from DOE facilities. Soil

Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 99-108.

-

Barnett, M. O.; Jardine, P. M.; Brooks, S. C.; Selim, H. M. Adsorption and

transport of uranium(VI) in subsurface media. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J.

2000, 64, 908-917.

-

Barnes, C. E.; Cochran, J. K. Uranium geochemistry in esturaine sediments:

Controls on removal and release processes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta

1993, 57, 555-569.

-

Grenthe, I.; Fuger, J.; Konings, R. J. M.; Lemire, R. J.; Muller, A. B.;

Nguyen-Trung, C.; Wanner, H. Chemical thermodynamics of uranium; North-Holland

Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.: Amsterdam, 1992; Vol. 1.

-

Liger, E.; Charlet, L.; Cappellen, P. V. Surface catalysis of uranium(VI)

reduction by iron(II). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 2939-2955.

-

Fredrickson, J. K.; Zachara, J. M.; Kennedy, D. W.; Duff, M. C.; Gorby, Y. A.;

Li, S. M. W.; Krupka, K. M. Reduction of U(VI) in goethite (a-FeOOH)

suspensions by a dissimilatory metal-reducing bacterium. Geochim. Cosmochim.

Acta 2000, 64, 3085-3098.

-

Lovely, D. R.; Phillips, E. J. P. Bioremediation of uranium contamination with

enzymatic uranium reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1992, 26,

2228-2234.

-

Gorby, Y. A.; Lovley, D. R. Enzymatic uranium precipitation. Environ. Sci.

Technol. 1992, 26, 205-207.

-

Wu, W.-M.; Carley, J.; Fienen, M.; Mehlhorn, T.; Lowe, K.; Nyman, J.; Luo, J.;

Gentile, M.; Rajan, R.; Wagner, D.; Hickey, R.; Gu, B.; Watson, D. B.; Cirpka,

O.; Kitanidis, P.; Jardine, P. M.; Criddle, C. Pilot-scale in situ

bioremediation of uranium in a highly contaminated aquifer. 1. Conditioning of

a treatment zone. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 3978-3985.

-

Wu, W.-M.; Carley, J.; Gentry, T.; Ginder-Vogel, M.; Fienen, M.; Mehlhorn, T.;

Yan, H.; Caroll, S.; Pace, M.; Nyman, J.; Luo, J.; Gentile, M.; Fields, M. W.;

Hickey, R.; Watson, D. B.; Cirpka, O.; Zhou, J.; Fendorf, S.; Kitanidis, P.;

Jardine, P. M.; Criddle, C. Pilot-scale in situ bioremediation of uranium in a

highly contaminated aquifer. 2. Geochemical control of U(VI) bioavailability

and evidence of U(VI) reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 3986-3995.

-

Anderson, R. T.; Vrionis, H. A.; Ortiz-Bernard, I.; Resch, C. T.; Long, P. E.;

Dayvault, R.; Karp, K.; Marutzky, S.; Metzler, D. R.; Peacock, A. D.; White, D.

C.; Lowe, M.; Lovley, D. R. Stimulating the in situ activity of Geobacter

species to remove uranium from the groundwater of a uranium-contaminated

aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2003, 69, 5884-5891.

-

Bertsch, P. M.; Hunter, D. B. In situ chemical speciation of uranium in

soils

and sediments by micro x-ray absorption spectroscopy. Environ. Sci.

Technol. 1994, 28, 980-984.

-

Wu, W.-M.; Carley, J.; Luo, J.; Ginder-Vogel, M.; Cardanans,

E.; Leigh, M. B.; Hwang, C.; Kelly, S. D.; Ruan, C.; Wu, L.; Gentry, T.; Lowe,

K.; Mehlhorn, T.; Carroll, S. L.; Fields, M. W.; Gu, B.; Watson, D.; Kemner, K.

M.; Marsh, T. L.; Tiedje, J. M.; Zhou, J.; Fendorf, S.; Kitanidis, P.; Jardine,

P. M.; Criddle, C. In situ bioreduction of uranium(VI) to submicromolar levels

and reoxidation by dissolved oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, Submitted.

|

| PDF

Version | | Lay Summary | |

Highlights Archive

|

| SSRL is supported

by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL

Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy,

Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes

of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology

Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |

|

Matthew

Ginder-Vogel1, Wei-Min Wu1, Jack Carley2,

Phillip Jardine2, Scott Fendorf1 and Craig

Criddle1

Matthew

Ginder-Vogel1, Wei-Min Wu1, Jack Carley2,

Phillip Jardine2, Scott Fendorf1 and Craig

Criddle1