The adaptive immune response enables the vertebrate immune system to recognize and respond to specific pathogens, with immunological memory allowing a stronger response upon subsequent re-exposure to a pathogen. Adaptive immunity relies on the capacity of immune cells to distinguish between the body's own cells and foreign invaders. ab T cell receptors (TCRs) recognize antigenic peptides in complex with major histocompatibility complex proteins (MHC) as the central event in the cellular adaptive immune response. Despite undergoing an extensive education process in the thymus, mature T cells exhibit a high frequency of crossreactivity, or alloreactivity, toward foreign peptide-MHC to which they have not previously been exposed. Alloreactivity indicates an inherent ability of the TCR to crossreact with a broad range of self and foreign peptide-MHC ligands, which could be beneficial for immune surveillance of a universe of potential pathogens. However, it presents a major clinical problem for organ transplantation in that genetically mismatched tissue can be rejected in a graft-host alloresponse.

The molecular basis of alloreactivity remains poorly understood, despite the

fact that the general structural principles of TCR/pMHC interactions have been

defined in approximately 14 cocrystal structures (Rudolph et al., 2006). More

broadly, receptor-ligand crossreactivity has been observed across many systems

and has generally been attributed to "molecular mimicry." However, structural

evidence for molecular mimicry, in the form of complexes between one receptor

and multiple similar, but distinct ligands, remains elusive for most systems.

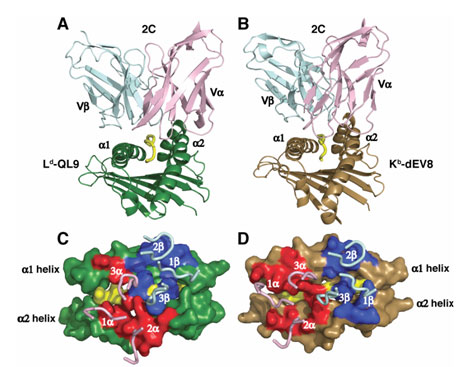

Figure 1: 2C TCR binding orientation with its self and foreign ligands.

(A,B) The a and b

chains

of the 2C TCR (pink and cyan) bind the peptide-MHC (A) foreign

(Ld-QL9, green

and yellow) and (B) self (Kb-dEV8 brown and yellow) ligands.

Only the Fv region

of the TCR and the a1 and a2 domains of the MHC are shown. (C,D) The

"footprint" view showing the isolated binding loops of the TCR over the surface

rendering of the (C) foreign and (D) self ligands. The

2C contact surface on

each peptide-MHC is drawn in red (Va) and blue

(Vb). (Colf et al., 2007)

The ability of a TCR to directly recognize foreign (allogeneic) MHC molecules

underlies T cell-mediated rejection in patients receiving allogeneic organ

transplants. In order to better understand the differences in recognition of

self versus foreign peptide-MHC complexes, we crystallized and solved the

structure of the 2C TCR bound to a foreign MHC, collecting data at SSRL

beamline 11-1. We compared our TCR/foreign MHC structure to the previously

published structure of the same TCR bound to a self MHC (Garcia et al., 1998),

revealing that instead of mimicking the interactions formed with a self MHC, a

single TCR adopts a completely different strategy to recognize a foreign MHC

(Figure 1). This is surprising, since the self and foreign MHC share 80%

sequence identity in the helices presented to the TCR. Very few conserved

interactions are found in the allogeneic and syngeneic complexes, and these

occur via largely unique binding chemistries. In addition, there does not

appear to be a focus on the polymorphic MHC residues presented to the TCR.

Thus, while sequence conservation between the self and foreign ligands might

have suggested similar recognition strategies, the interatomic contacts

highlight a vastly different mode of recognition.

In addition to the co-complex structure described, we also crystallized and

solved the structure of an engineered, high-affinity variant of the 2C TCR

bound to the same foreign MHC. In this structure, the data for which were also

collected on beamline 11-1 at SSRL, the "wild-type" recognition footprint

persists despite modified interactions with the peptide, indicating that

differences in the antigenic peptide are not necessarily sufficient to alter

TCR recognition.

Thus, we show that a single TCR recognizes two globally similar, but distinct

ligands by divergent mechanisms, indicating that receptor-ligand

crossreactivity can occur in the absence of molecular mimicry.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI 48540 (K.C.G.) and GM55767 (D.M.K.), a

National Science Foundation predoctoral fellowship (L.C.), the Keck Foundation,

and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Primary Citation

References

Colf, L.A., Bankovich, A.J., Hanick, N.A., Bowerman, N.A., Jones, L.L., Kranz,

D.M., and Garcia, K.C. (2007). How a single T cell receptor recognizes both

self and foreign MHC. Cell 129, 135-146.

| SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |