Transcription is the first step and the key control point in the pathway of

gene expression. Transcriptional regulation underlies development, oncogenesis,

and other fundamental processes. The central enzyme in transcription is RNA

polymerase, in eukaryotic cells there are three forms of RNA polymerase,

designated I, II, and III (or A, B, and C), made up of 10-15 polypeptides. The

fundamental mechanism of transcription is conserved among cellular RNA

polymerases. Common features include an unwound region, or "transcription

bubble," of about 15 base pairs of the DNA template and some eight residues of

the RNA transcript hybridized with the DNA in the center of the bubble. These

enzymes are capable of both forward and retrograde movement ("backtracking") on

the DNA. Forward movement is favored by the binding of nucleoside triphosphates

(NTPs), while backtracking occurs especially when the enzyme encounters an

impediment, such as damaged DNA. All NTP's can bind the entry or "E" site,

whereas only an NTP matched for base pairing with the DNA template binds the A

(addition) site for addition to the growing RNA chain (1).

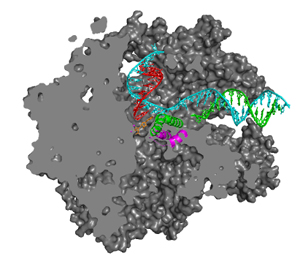

Figure 1. Cutaway view of the Pol II transcribing

complex. Template DNA, nontemplate DNA, RNA, GTP in the A site, are shown in

cyan, green, red, orange, respectively. The bridge helix (Rpb1 815- 848) is in

green; trigger loop (Rpb1 1065-1110) is in magenta and Mg2+ ions are

shown in magenta spheres. The pol II surface is shown in gray.

The way in which the correctly matched and positioned NTP is recognized and how

this recognition leads to catalysis remain obscure. The energies of base

pairing and stacking are insufficient for base selectivity, and the question

arises of why transient occupation of the A site by either incorrect NTP or

2'-dNTP substrates does not lead to erroneous RNA synthesis. Genetic and

biochemical studies have implicated two conserved polymerase domains, termed F

and G, in the transcription mechanism (2,3).

Structural studies have identified these two domains with elements adjacent to

the polymerase active site, termed the bridge helix (F) and trigger loop (G)

(4). In the x-ray structures of transcribing complexes,

however, no contact of these structural elements with NTP in the A or E sites

has been observed. The present work describes a series of pol II transcribing

complex structures that reveal such contacts and suggest the roles of these

domains in the transcription mechanism (Figure 1).

The trigger loop is a mobile element, allowing entry of NTP into the E and A

sites in conformations previously observed, and sealing off the A site in the

conformation reported here. Located beneath NTP in the A site, the trigger loop

directly contacts the base and b-phosphate, and

indirectly contacts 2'- and 3'-OH groups of the ribose sugar as well. Numerous

interactions with other pol II residues serve to configure and position the

trigger loop, so it reads out not only the chemical nature of the NTP but also

the parameters of the DNA-RNA hybrid helix in the A site. A well-defined

conformation of the trigger loop may be capable of readout to ┼ngstrom

precision. Inasmuch as the hybrid helix differs substantially from B-form DNA

(difference of 3 ┼ in minor groove width and 5.5 ┼ in root-mean- square

phosphorous positions), such readout would readily distinguish ribo from

deoxyribo NTPs, as well as providing powerful discrimination against

purine-purine and pyrimidine-pyrimidine mispairing.

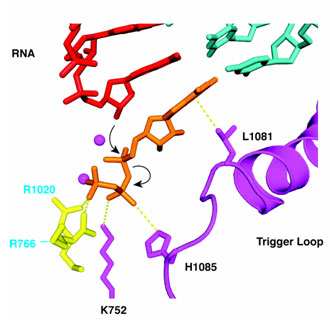

Figure 2. The pol II "trigger loop" forms a network

of interactions with a nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) in the active center. When

base, sugar, and phosphates are all correct, a histidine residue of the trigger

loop is aligned with the b-phosphate, facilitating

nucleophilic attack by the RNA 3'-OH and phosphodiester bond formation. In this

way, the trigger loop couples nucleotide selection to catalysis.

Two further features of trigger loop interaction may be crucial for

transcription. First, the contact of His1085 with the NTP b-phosphate noted

above may be key to catalysis. The distance between the imidazole N-H group and

b phosphate oxygen is about 3.5 ┼, optimal for hydrogen bonding or salt bridge

interaction. The protonated imidazole group would be expected to withdraw

electron density from the phosphate and facilitate SN2 attack of the

RNA 3'- terminal OH group, leading to phosphodiester bond formation (Figure

2). Second, trigger loop interaction with NTP in the A site is evidently poised

on the verge of stability, since the interaction could only be detected with

improved data quality and analysis. If any feature of the NTP or its location

is incorrect, the interaction will be lost.

The trigger loop may therefore couple nucleotide recognition to catalysis. In

the presence of matched rNTP in the A site, it will swing into position and

literally "trigger" phosphodiester bond formation (Figure 2). An incorrect NTP

in the A site will not support trigger loop interaction and so is unlikely to

undergo catalysis. When reaction with a correct NTP does occur, the release of

pyrophosphate disrupts contact with His1085, likely destabilizing trigger loop

interaction and freeing the DNA-RNA hybrid for translocation. Movement of the

trigger loop, coupled to that of the bridge helix (Figure 2), may contribute to

the translocation process (3,5).

Primary Citation

References

Wang, D., Bushnell, D.A., Westover, K.D., Kaplan, C.D., and Kornberg, R.D.

(2006) Structural basis of transcription: role of the trigger loop in substrate

specificity and catalysis. Cell 127, 941.

| SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |