Membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to crystallize, and fiber-forming

proteins were actually declared "uncrystallizable" by the eminent x-ray

crystallographer Sir Lawrence Bragg. Supported by the facilities and staff at

SSRL, a team of researchers has recently determined structures that solved both

problems by defining the atomic structure of the membrane-associate protein

pilin and its assembled Type IV pilus (T4P) fiber structure. T4P are

filamentous organelles displayed on the surfaces of most Gram-negative bacteria

1. T4P are central to host colonization for many bacterial pathogens, mediating

diverse and essential functions such as motility, adhesion, microcolony

formation and uptake of DNA and specific filamentous phage. T4P are several

microns in length and only 60-90 Å in diameter, and are comprised of thousands

of copies of a single subunit, the pilin protein. Type IV pilins from different

bacterial species share a common sequence of mostly hydrophobic amino acids in

their N-terminus, as well as a pair of cysteines in their C-terminus, but

differ substantially beyond these sites. Their prominent exposure on the

bacterial surface and their key functions in virulence make T4P attractive

targets for vaccines and therapeutics, the design of which would greatly

benefit from their detailed molecular structures. Structural analyses of the

Type IV pili have, however, proved to be extremely challenging. The presence of

the hydrophobic N-terminal segment, which allows pilin to assemble and

disassemble from the cell membranes, makes the pilin subunits insoluble without

detergent. This problem has hindered efforts to crystallize the full-length

proteins. Furthermore, the extremely thin and featureless pilus filaments

reveal scant information on their helical symmetry, and thus resist classical

helical image reconstruction approaches using electron micrograph (EM) images.

Membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to crystallize, and fiber-forming

proteins were actually declared "uncrystallizable" by the eminent x-ray

crystallographer Sir Lawrence Bragg. Supported by the facilities and staff at

SSRL, a team of researchers has recently determined structures that solved both

problems by defining the atomic structure of the membrane-associate protein

pilin and its assembled Type IV pilus (T4P) fiber structure. T4P are

filamentous organelles displayed on the surfaces of most Gram-negative bacteria

1. T4P are central to host colonization for many bacterial pathogens, mediating

diverse and essential functions such as motility, adhesion, microcolony

formation and uptake of DNA and specific filamentous phage. T4P are several

microns in length and only 60-90 Å in diameter, and are comprised of thousands

of copies of a single subunit, the pilin protein. Type IV pilins from different

bacterial species share a common sequence of mostly hydrophobic amino acids in

their N-terminus, as well as a pair of cysteines in their C-terminus, but

differ substantially beyond these sites. Their prominent exposure on the

bacterial surface and their key functions in virulence make T4P attractive

targets for vaccines and therapeutics, the design of which would greatly

benefit from their detailed molecular structures. Structural analyses of the

Type IV pili have, however, proved to be extremely challenging. The presence of

the hydrophobic N-terminal segment, which allows pilin to assemble and

disassemble from the cell membranes, makes the pilin subunits insoluble without

detergent. This problem has hindered efforts to crystallize the full-length

proteins. Furthermore, the extremely thin and featureless pilus filaments

reveal scant information on their helical symmetry, and thus resist classical

helical image reconstruction approaches using electron micrograph (EM) images.

John Tainer and colleagues at the Scripps Research Institute have succeeded in

solving the crystal structures of Type IV pilins from several important human

pathogens using the macromolecular crystallography beamlines at SSRL (Beamlines

7-1, 9-1, 9-2 and 11-1). This success built directly upon the earlier efforts

of Tainer group members Hans Parge and Andrew Arvai who made the original

breakthrough pilin structure determination as aided enormously by the then new

area detectors installed at SSRL according to John Tainer 2. Full length

pilin structures were determined for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and a truncated structure lacking the

hydrophobic N-terminus was determined for

Vibrio cholerae 2, 3. In a recently published article in

Molecular Cell, this

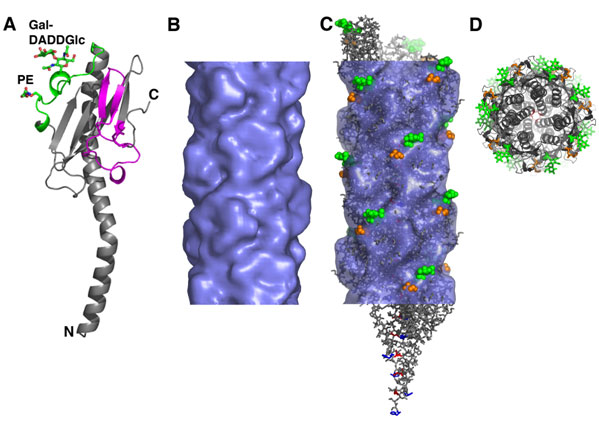

group report the 2.3 Å structure of N. gonorrhoeae (GC) pilin along with

a "pseudo-atomic" structure of the pilus filament, solved by combined cryoEM

reconstruction methods and computational docking of the pilin crystal

structure 4. The N. gonorrhoeae Type IV pili are

displayed peritrichously on the bacterial surface and mediate a multitude of

functions in virulence, including immune escape. They share substantial

sequence identity with the Type IV pili of N. meningitidis, which causes

meningitis. The GC pilin crystal structure nicely extends the previous

structure solved by the same group 2, and furthermore reveals

the precise identity of two unusual post-translational modifications: an

O-linked galactose (a1→3)

diacetamidodideoxyglucose at Ser63 and a phosphoethanolamine at Ser68 (Fig.

1A). These post-translational modifications undergo phase variation and may

also vary in structure from one generation of N. gonorrhoeae to the

next, and have been proposed to function in immune escape. Another unusual

feature of the pilin subunits is the "hypervariable loop", a segment between

residues 128 and 141 that undergoes extreme sequence variation. This loop

protrudes from the back of the pilin globular domain. The remainder of the GC

pilin protein looks similar to other pilins: the hydrophobic N-terminus forms

an extended a-helix, half of which is embedded in a

b-sheet within the C-terminal globular domain.

Figure 1 Structure of the N. gonorrhoeae Type IV pilus by

x-ray crystallography and cryoEM reconstruction. (A) GC pilin structure at

2.3 Å showing the postranslational modifications galactose (a1→3) diacetamidodideoxyglucose (Gal-DADDGlc) at Ser63

and a phosphoethanolamine (PE) at Ser68. The hypervariable loop is colored

magenta. (B) CryoEM reconstruction of the GC pilus filament and

(C) the pseudoatomic resolution structure of the filament fit into the

EM density. (D) End view of the pilus structure showing the packing of

the N-terminal a-helices and the protruding

postranslational modifications and hypervariable loop.

Tainer and colleagues collaborated with Ed Egelman at the University of

Virginia to determine a cryoEM reconstruction of the GC pilus filament using

Egelman's Iterative Helical Real Space Reconstruction software 5. Although the

filaments appear to be very smooth and featureless when examined by EM, they

are in fact highly corrugated (Fig. 1B). The pilus structure was built by

computationally fitting the pilin subunit structure into the cryoEM density and

generating a filament using the symmetry operators determined for the

reconstruction. In this pseudoatomic resolution pilus structure, deep grooves

run between the subunits, and ridges formed by the post-translationally

modified regions and the hypervariable loop protrude from the filament surface

(Fig. 1C). The filaments are held together primarily by the N-terminal

segments, which form a helical array in the core of the filament (Fig. 1D).

The N. gonorrhoeae Type IV pilus structure provides important insights

into both pilus assembly and functions in pathogenesis. The filament can be

viewed as three helical pilin polymers that twist around each other. These

polymers are likely to be assembled simultaneously at the inner membrane of the

bacteria, from a reservoir of pilin subunits that are anchored in the membrane

via their hydrophobic N-termini. Importantly, the pilin and pilus structures

provided the basis for a unified model for the assembly of these filaments that

was recently supported by structures of the secretion superfamily ATPase

6,

which were also done partly at SSRL and show the basis for the piston-like

shifts to push T4P out by two helical turns. The grooves that run along the

filament surface are positively-charged and represent an ideal, non-specific

binding site for DNA, which can be brought into the cell by pilus retraction.

And the locations of the variable post-translational modifications and

hypervariable loop on protruding ridges on the filament would mask recognition

of more conserved regions of the protein by protective antibodies. This

structure is the first such structure determined for a Type IV pilus filament.

The overall architecture of the filament is expected to be shared by all Type

IV pili based on sequence and structure conservation for the pilin subunits. It

is the regions of the subunit that vary, quite dramatically, among the pilins,

that are exposed on the pilus surface and define its chemistry and hence its

functions. This molecular understanding of a Type IV pilus filament reveals new

targets for antibacterial agents that may have broad specificity.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI22160 (JAT, LC), EB001567 (EHE) and

GM076503 (NV) and a fellowship from The Canadian Institutes of Health Research

(LC).

Primary Citation

References

Craig, L. et al. Type IV Pilus Structure by Cryo-Electron Microscopy and

Crystallography: Implications for Pilus Assembly and Functions. Molecular Cell

23, 651-662 (2006).

| SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |