|

|

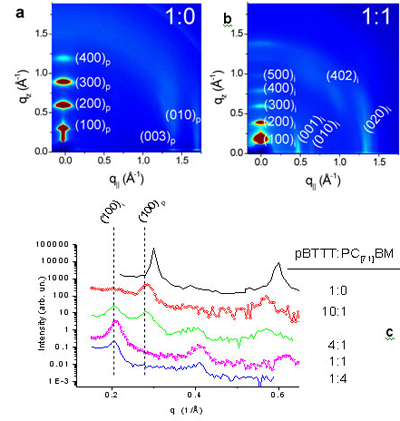

| Figure 1: Diffraction data for pBTTT:PC[71]BM blends of varying weight ratio that have been annealed at 185 °C for 10 minutes. The annealing took place at the glass transition temperature of pBTTT in order to increase the molecular order. (a) 2D GIXS of pure pBTTT. (b) 2D GIXS of 1:1 pBTTT:PC[71]BM blend. (c) High resolution specular x-ray diffraction for a series of pBTTT:PC[71]BM blends. This confirms the expansion perpendicular to the substrate. | |

Stanford and SLAC researchers have recently investigated a highly crystalline

polymer that reaches optimal solar cell efficiency at 80% fullerene content.

X-ray diffraction measurements (see figure 1) performed at the Stanford

Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) have shown the existence of a highly

ordered bimolecular crystal (a structure wherein two distinct chemical species

arrange in an ordered fashion on a lattice). This crystal forms when the

fullerene molecule intercalates between the side-chains of the semi-crystalline

polymer (see figure 2). While such co-crystals of fullerenes and small organic

molecules have been observed before, this is, to our knowledge, the first

report of a fullerene-polymer co-crystal. Furthermore, this unexpected

intercalation is observed in several polymer:fullerene blends and suggested by

the researchers for several others. These results explain the origin of the

optimal 1:4 blending ratio in these blends: this ratio yields a two phase film

that consists of the bimolecular crystal and a pure fullerene phase with

approximately equal volumes, while for a blend ratio of ~1:1 only the pure

bimolecular crystal forms.

The research team has specifically studied thin film BHJs of

poly(2,5-bis(3-tetradecyllthiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene) (pBTTT) and

either phenyl-c61-butyric acid methyl ester (PC[61]BM) or

phenyl-c71-butyric acid methyl ester (PC[71]BM). pBTTT is a

well-ordered semicrystalline polymer that has high charge carrier mobility (see

SSRL highlight on Highly

Oriented Crystals in Polythiophenes for details). The 1:1 pBTTT:PCBM blends

had a solar cell efficiency of only 0.16%, while 1:4 blends had an efficiency

of 2.35%. X-ray diffraction measurements on SSRL beam lines 7-2, 2-1 and 11-3

were conducted to understand these unexpected results. Typical data are shown

in Fig. 1 for pure pBTTT and a series of pBTTT:PC[71]BM blends of

varying weight ratio. These specular scans (fig. 1c) demonstrate the shift in

the lattice perpendicular to the substrate as PC[71]BM is added. The

specular x-ray pattern for the pristine pBTTT film (black line) shows that the

d-spacing is 21.15 Å. The scan for the 4:1 blend (green line) shows the

presence of a shifted peak for the 10:1 blend (shifted due to defects in the

PBTTT), but most importantly, a new peak emerges with an expanded d-spacing of

30.2 Å. With the addition of more fullerene, the peak corresponding to

the intercalated lattice increases in intensity and the 22.1 Å peak

associated is completely suppressed at a blending ratio of 1:1. The existence

of two sets of peaks shows that the fullerenes are not distributed uniformly

throughout the film, but form distinct phases: pure pBTTT and the

pBTTT:PC[71]BM intercalated phase. We use the subscript "p" to refer

to the pristine pBTTT lattice, while the intercalated phase peaks are noted

with the subscript 'i'.

Additional diffraction data were obtained using 2D grazing incidence x-ray

scattering (2D GIXS) for several pBTTT:PC[71]BM blends. The 2D GIXS

for a pristine pBTTT film (Fig. 1a) is consistent with the literature and

displays several diffraction peaks along the vertical slice at q||

≈ 0. These peaks are (100)p, (200)p, etc. and

correspond to a lamellar d-spacing of 21.15 Å, consistent with the higher

resolution data in Fig 1c. The scattering for pristine pBTTT also exhibits two

vertical streaks at q|| equal to 1.41 Å-1 and 1.71

Å-1 corresponding to the intramolecular (003)p and

the pi-stacking (010)p, respectively. The 2D GIXS pattern for a 1:1

pBTTT:PC[71]BM blend, shown in Fig. 1b, is significantly different

from the pattern for the pristine film in that the peaks along the vertical

slice at q|| ≈ 0 are shifted and now correspond to the

d-spacing of 30.2 Å. There are several new streaks that appear along

q||

with the strongest at 0.49 and 0.67 Å-1 and a broad, mixed

index peak at q|| = 1 Å-1 and qz = 0.8

Å-1. The 2D GIXS pattern for the 1:4 pBTTT:PC[71]BM

blend contains these peaks which we associate with the intercalated lattice as

well as a halo around 1.4 Å-1. This halo corresponds to a pure

amorphous PC[71]BM phase that arises when phase separation occurs.

The absence

of the fullerene halo in the 2D GIXS pattern for the 1:1 blend is additional

evidence for the fullerene being intercalated between the polymer side-chains.

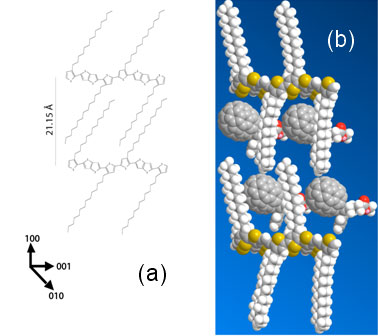

We attribute the ~9 Å increase in the d-spacing normal to the substrate

(21.1 to 30.2 Å) to the intercalation of the PC[71]BM in

between the side-chains of the pBTTT. A space-filling schematic of pBTTT and

PC[71]BM drawn to scale is shown in Fig 2(b) and demonstrates how

the side-chain spacing along the polymer backbone allows for this. A

preliminary unit cell is assigned based on the diffraction data: a triclinic

lattice with a = 30 Å, b = 9.9 Å, c = 13.5 Å, a = 72°, B ≈

90°, and

g ≈ 90°. This is in contrast to the

reported orthorhombic pBTTT lattice of a = 22.15 Å, b= 3.67 Å, and

c = 13.37 Å (although it appears the lattice is actually triclinic with a

= 19.6 Å, b = 5.4 Å, c = 13.6 Å, a =

136°, B =

84° and g = 86°). The

preliminary bimolecular lattice preserves the intramolecular (c axis) spacing,

but there is a doubling along the b-axis due to the presence of the PCBM;

hence, there are two polymer molecules along the b direction. A more detailed

structural analysis is in progress at SSRL.

For all the polymers studied by the Stanford/SLAC research team, they found

that if there was ample room between the polymer side-chains, then

polymer:fullerene intercalation occurred. It is, however, not yet clear if

intercalation is desirable for solar cell devices. It will be necessary to

adjust the position of fullerenes and other electron acceptors with different

shapes and sizes to determine if intercalation is beneficial for solar energy

conversion. None-the-less, our findings suggest that separate models of

recombination should be developed for the two different kinds of cells that

form depending on whether or not intercalation occurs.

Primary Citation

"Bimolecular crystals of fullerenes in conjugated polymers and the implications

of molecular mixing for solar cells", A.C. Mayer, M.F. Toney, S.R. Scully, J.

Rivnay, C.J. Brabec, M. Scharber, M. Koppe, M. Heeney, I. McCulloch, M.D.

McGehee, Adv. Func. Mater. 19, 1173-1179 (2009).

This research shows that the rational design of polymers for BHJ solar cells

must consider the possibility of bimolecular crystal formation in efforts to

push the efficiency higher. These discoveries further suggest a method of

intentionally designing bimolecular crystals and tuning their properties to

create novel materials for photovoltaic and other applications such as LEDs,

LASERs and biosenors.

Figure 2:

Possible bicrystal structure showing the effect of PC[71]BM

intercalation on the crystal lattice of pBTTT. (a) pristine pBTTT (b)

Schematic of intercalated pBTTT:PC[71]BM. The

PC[71]BM is placed within the

intercalated pBTTT:PC[71]BM in order to agree with the d-spacings found in

x-ray scattering. The lattice axes are shown in the lower left corner for

reference.

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.