John R. Bargar1, Samuel M. Webb2, and Bradley M. Tebo2

1Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory

2Oregon Health and Sciences University

|

|

|

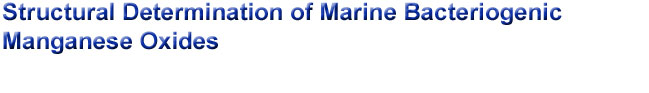

Figure 1. Top: Half of the Earth's annual photosynthetic CO2 fixation budget is attributable to oceanic phytoplankton. Mangan-ese required for this photo-synthetic activity is derived largely from bacteriogenic man-ganese oxides. Bottom: man-ganese oxides precipitated around a spore (cell) of the marine Mn(II)-oxidizing bac-terium, Bacillus sp., strain SG-1. This cell is about 0.5 µm diameter (small axis). | |

Bacterial oxidation of Mn(II) impacts the global geochemical cycling of carbon,

nitrogen, sulfur, nutrients, and contaminants in the environment. Manganese is

abundant in the biosphere (~1014 Kg of suspended and dissolved

manganese in the oceans) and is second only to iron in relative terrestrial

abundance of transition metals. Manganese is an important nutrient in the

marine water column and is fundamentally required for photosynthesis. The

acquisition of manganese by organisms and the biogeochemistry of manganese in

the oceans is therefore an essential part of global carbon fixation processes

(i.e., uptake and conversion of CO2 to organic molecules,

biomass). Manganese oxides are formed in sea water via bacterial catalysis of

the oxidation of dissolved Mn(II) to Mn(IV) (Tebo et al.,

2004). The oxides form external to bacterial cells (on cell surfaces or

bacterial exopolymers) and subsequently settle through the marine water column,

where they are available to react with dissolved ions. Bacteriogenic manganese

oxides have high surface areas, are among the strongest sorbents of heavy

metals, and are powerful oxidants of organic materials. Via sorption and

oxidation/reduction reactions, settling manganese oxides help to mediate the

trace element and nutrient composition of sea water. One of the most

fundamental of scientific questions relating to this subject is, "What are the

structures and compositions (i.e., the identities) of marine bacteriogenic

manganese oxides?". Identifying marine manganese oxides will substantially

enhance our ability to model and understand their roles in maintaining the

chemistry of the oceans. This information will also directly contribute to a

greater understanding of the properties of bacteriogenic manganese oxides,

which are of great interest for their potential technological applications.

A collaborative group of scientists from SSRL and the Oregon Health and Science

University have used the in-situ synchrotron-based techniques, EXAFS

(extended x-ray absorption fine structure) spectroscopy and XRD (x-ray

diffraction), to determine the identities of manganese oxides formed in sea

water by the marine bacterium, Bacillus sp., strain SG-1. Both

techniques provide information regarding the molecular-scale structures

(i.e., the arrangement of atoms) of the bacteriogenic oxides. These

techniques are highly complementary; EXAFS is primarily sensitive to variations

in the local structure (up to about 6 Å) around manganese atoms

and can be measured from noncrystalline substances such as amorphous colloids

and species dissolved in solution. In comparison, XRD is highly sensitive to

the long-range structure (up to about 20 Å), disorder, and particle size in

crystalline materials averaged over the entire unit cell

(i.e., the fundamental

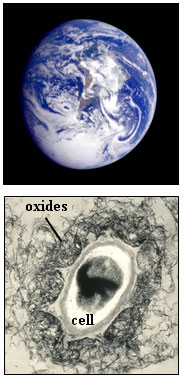

Figure 2. (A) X-ray diffraction intensity data for bacteriogenic

manganese

oxides produced in sea water. The bottom pattern is for clean cells. (B) X-ray

diffraction intensity data for synthetic birnessite reference compounds. From

Webb et al. (2005a).

X-ray diffraction data for bacteriogenic manganese oxides grown in sea water

are shown in Figure 2(a) (Webb et al., 2005a). The data

for the samples reacted for ≥ 24 hr are similar to the x-ray diffraction

pattern for the layered Mn(IV) oxide, c-disordered hexagonal birnessite (figure

2(b)); Most importantly, they exhibit strongly asymmetric (200)/(110) peaks (at

ca 1.4 Å) and (310)/(020) peaks (ca 2.4 Å). This result

qualitatively suggests

that the bacteriogenic oxides are layered manganese oxides. The layer repeat

distance of the bacteriogenic oxides is 10 Å, as indicated by the position of

the (001) peak. Close inspection of the sample patterns reveals small peaks

that indicate the presence of a related layered manganese oxide, triclinic

birnessite. In particular, the presence of two (310)/(020) diffraction peaks

and a small peak on the left-hand side of the (200)/(110) peak indicate that

the birnessite layer unit cell has undergone a slight transformation (a slight

lengthening along one of the unit cell axes), causing a breakdown of the

initial hexagonal symmetry (the designation "triclinic" indicates the lowest

possible unit cell symmetry). The x-ray diffraction pattern for the 12 hr

sample shows only hexagonal birnessite peaks, suggesting that it is the initial

phase. Note that the peaks are very weak and broad for this sample, indicating

very poor crystallinity of the material. If bacteriogenic manganese oxides are

grown in a NaCl solution, which is devoid of Ca2+, Mg2+

and other important

ions in sea water, then the resulting primary bacteriogenic oxides remain very

poorly crystalline (no diffraction peaks), and hexagonal birnessite is not

produced over this time scale (Bargar et al., 2005; Webb

et al., 2005b). This

comparison suggests that one of the major ions in sea water is required to

generate or stabilize these marine birnessites. Subsequent measurements have

shown this ion to be Ca2+, which is incorporated in the interlayer of the oxide

structure (Webb et al., 2005a).

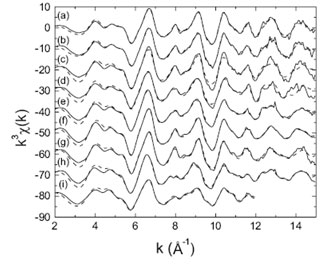

Figure 3. EXAFS spectra for bacteriogenic manganese oxides produced in

sea water. Solid lines indicate experimental data and dashed lines indicate fits.

(a-e) bacteriogenic manganese oxides: (a) t=6h, (b) t=12h, (c) t=24h, (d)

t=50h, (e) t=80h. (f-i) reference compounds: (f) d-MnO2, (g) hexagonal

birnessite, (h) triclinic birnessite, (i) todorokite. From Webb

et al., (2005a).

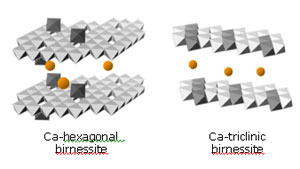

Figure 4.

Polyhedral illustration of the proposed bacteriogenic manganese oxides produced

in sea water. Octahedra denote the positions of MnO6 groups (Mn atoms in the

center, oxygen atoms at the corners). Light-colored octahedra are Mn(IV),

dark-colored octahedra are Mn(III). Orange spheres show interlayer

Ca2+

cations. Mn(III) cations are partially ordered into rows in the triclinic

birnessite structure, which breaks the hexagonal layer symmetry of the

hexagonal birnessite.

The conclusion from both sets of measurements is that the bacteriogenic

manganese oxide produced in sea water is a poorly crystalline layered manganese

oxide, birnessite. No other forms of manganese oxide were observed. One

important process that this result helps to illuminate is the photocatalyzed

reductive dissolution of manganese oxides in sea water (i.e.,

sunlight-driven reduction of Mn(IV) to Mn(II), followed by release of Mn(II)).

This reaction occurs in the surface mixed layers of the oceans, where it helps

to maintain a pronounced manganese concentration maximum (Sunda

and Huntsman, 1988). Birnessite is particularly susceptible to

photo-stimulated reductive dissolution (Sherman, 2005). Thus,

the dominance of birnessite as the primary bacteriogenic marine manganese oxide

would help to explain this chemical behavior in the surface layers of the

oceans.

This work was support by the National Science Foundation, Chemistry Division

and Earth Sciences Division. This research was carried out at the Stanford

Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, a national user facility operated by Stanford

University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy

Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the

Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by

the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources,

Biomedical Technology Program.

Primary Citation:

References:

crystal structure repeat unit). Both techniques can be used to measure wet,

undisturbed samples, which is critical for capturing the chemistry that occurs

under natural wet conditions.

EXAFS spectra for bacteriogenic manganese oxides grown in sea water are shown

in Figure 3. Visual inspection of figure 3 shows that the sample spectra ((a) -

(e)) match the spectra for hexagonal birnessite (spectrum (g)) and

s-MnO2

(spectrum (f)), which is a disordered form of hexagonal birnessite. Fits to the

EXAFS spectra indicate the initial bacteriogenic product to be a layered

hexagonal birnessite and provide the positions of atoms within the manganese

oxide layer. EXAFS fits further indicate that the structure contains numerous

Mn(IV) vacancy defects (~ 14% of all manganese sites are empty), which

contribute substantially to the chemical reactivity of this material. With

time, a small fraction of triclinic birnessite appears. Integration of the

EXAFS and XRD results allows the structures of the bacteriogenic oxides to be

reconstructed, as shown in figure 4.

S. M. Webb, B. M. Tebo, and J. R. Bargar, "Structural Characterization of

Biogenic Mn Oxides Produced in Seawater by the Marine Bacillus sp. Strain

SG-1", Am. Mineral. 90,

1342 (2005)