Scott Pegan1, Christine Arrabit2, Wei Zhou1, Witek Kwiatkowski1, Anthony Collins3, Paul Slesinger2 and Senyon Choe1

Structural Biology1 and Peptide Biology2 Laboratories, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, Ca 92037; Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences3, College of Pharmacy, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331

The family of inwardly-rectifying potassium (Kir) channels of eukaryotic cells

are unique because they conduct K+ ions better in the inward than

outward direction. In native tissues, the small outward K+ current

through Kir channels influences the resting membrane potential and membrane

excitability. The major structural mechanism underlying inward rectification

involves a physical occlusion of the pore by polyamines and Mg2+

from the cytoplasmic side of the channel1,2. In addition to the property of inward rectification, Kir

channels respond to a variety of intracellular messengers, including G proteins

(Kir3 channels), ATP (Kir6 channels) and pH (Kir1 channels)3. The aberrant activity of Kir channels has been linked to a

variety of endocrine, cardiac and neurological disorders. For instance, the

loss of Kir3 channels leads to hyperexcitability and seizures in the

brain4, cardiac abnormalities5 and hyperactivity and reduced anxiety. Mutations in Kir1

and Kir2.1 channels have been implicated for Bartter's syndrome6 and Andersen's syndrome7,

respectively. The high resolution structures of Kir 3.1 and Kir 2.1,

elucidated with data collected at SSRL 9-1 and ALS respectively, yielded

insight into the gating, inward rectification, and causes of Andersen's

Syndrome.

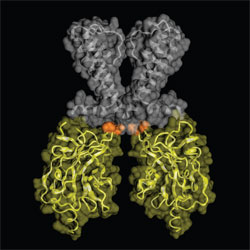

By comparing the Kir3.1 and Kir2.1 structures, a high degree of flexibility was

observed at the narrowest region of the channel's tetrameric pore, the G-loop

(Figure 1). The G-loop contains several small or hydrophobic residues and is

anchored by glycine. In the Kir3.1 structure solved at SSRL, the distance at

the narrowest point of the G-loop was 9.0 Å between the atomic centers of

diagonally-positioned subunits, which differed from the 5.7 Å distance observed

for equivalent positions of A306 in the Kir2.1 structure. Thus, the physical

opening formed by four opposing hydrophobic G-loops is too narrow to

accommodate a hydrated potassium ion to pass and leads us to conclude that the

Kir3.1 and Kir2.1 structures are of a closed state. Mutations, based on the

structure and studied by eletrophysiology, dramatically reduced the flexibility

of the G-loop. Bulky sidechains in the G-loop chains inhibited channel

current. These results reinforce the role of the G-loop to form the closed

state.

The elucidated structures not only showed insight into the gating of the Kir

family of channels but also lead to a better understanding of the inward

rectification properties of this family of channels. By studying the

electro-potential surfaces of the Kir3.1 and Kir2.1 structures, the Kir2.1

structure shows a remarkably high degree of electronegative surface potential

as compared to that of Kir3.1. Interestingly, a recent structure of

KirBac1.1's cytoplasmic pore exhibits less electronegative surface than Kir3.1.

Previously, the strong rectification of Kir2.1 has been attributed to two

principal electronegative regions; D172 in the M2 domain8 and E224/E299 in the cytoplasmic domains9,10. Using the structure of Kir2.1 as a

guide and electrophysiology experiments to confirm our findings, we identified

that D255 and D259 are linked to Kir2.1's strong rectification properties

unlike other members in the Kir family.

The Kir2.1 structure allowed the first structural understanding of Andersen's

Syndrome. Out of the eighteen positions in the Kir2.1, ten were visualized

with eight located on the top surface of the cytoplasmic structure (R189, T192,

R218, G300, V302, E303, R312, D314-315), which may

be near the punitive PIP2

(phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate)-binding site, and the other two buried

in the protein interface (G215D, N216H). Some of these residues are

interestingly close to the G-loop region and generally result in a loss of

function via dominant negative interactions and heteromeric assembly

7. For all

but one mutation, G300V, the resulting mutant protein was aggregated, pointing

to folding and tetramerization defects as the main reason for the disease. To

validate the point, one of the mutations known to disrupt a charged pair

interaction, R218Q, was rescued from the folding defect by a compensating

mutation to R/K at T309 as predicted by the Kir2.1 structure.

The elucidated structures of the Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 cytoplasmic domains have

provided us with a broader understanding of how this channel gates and

rectifies itself. Furthermore, the electrophysiology experiment of the

Andersen's Syndrome mutates coupled with the structural information has allowed

for the first time to provide an explanation of how these mutations could

interfere with the folding and gating of the Kir2.1 channel. Our better

understanding may lead to therapeutic treatments for the disease.

Primary Citation:

References:

Pegan, S., Arrabit, C., Zhou W., Kwiatkowski W., Collins A., Slesinger

PA., Choe, S. (2005) Cytoplasmic domain structures of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 shows

sites for modulating gating and rectification. Nat Neurosci. 8:

279-287

| SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |