|

|

|

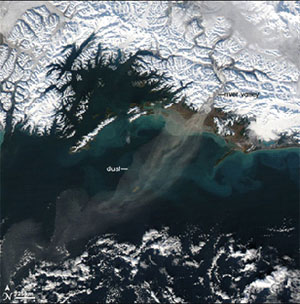

Figure 1.

Dust storm blowing glacial dusts from the Copper River Basin of southeast

Alaska into the North Pacific Ocean, which depends on this and other external

iron sources to support its biological communities. (Image: NASA MODIS

satellite image, Nov. 1, 2006.

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=7094) |

|

External supplies of iron to the world's oceans come largely from fine

sediments and dusts that can be transported from continents by ocean currents,

or as aerosols deposited on the ocean surface. Aerosols are most notably

derived from arid and seasonally-arid areas, where winds can entrain

significant particulates and transport them long distances. Glaciers also

produce considerable sediments that can form aerosols; Alaska contains numerous

glaciers that efficiently grind rock that delivers both aerosols and suspended

sediments to the Gulf of Alaska (Figure 1). Anthropogenic aerosols from fossil

fuel emissions and other sources are can be important in some areas.

This work has three important implications to our understanding of iron cycling

in the ocean. This work provides a chemical basis for the substantial

differences in iron solubility for different iron particles. Second, it shows

that glacial processes can affect the ocean in complex and previously

unexplored ways. As glaciers recede in response to global climate change, the

increased dust delivery to the oceans may serve as a feedback mechanism to

influence atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and thereby moderate climate

change. At very least, changes in climate will affect the distribution and

source of dust sources to the world's oceans, thereby affecting marine

productivity and the global carbon cycle. Third, this work highlights the

potentially important role of anthropogenic aerosols in regulating dissolved

iron levels, and thus photosynthesis, in the oceans. In the North Pacific

Ocean, the increased fossil fuel use in China and elsewhere in Asia may

increase the aerosol concentration of oil fly ash. Since oil fly ash is highly

soluble, this increase could profoundly affect primary production.

Primary Citation

Andrew W. Schroth, John Crusius, Edward R. Sholkovitz and Benjamin C. Bostick,

"Iron solubility driven by speciation in dust sources to the ocean", Nature

Geosci., 2, 337-340 (2009).

Further Readings

For more on the role of iron in the oceans, see the following: (a) Martin, J.

H., Gordon, R. M. & Fitzwater, S. E. Limnol. Oceanogr. 36,

1793-1802 (1991).; (b) Moore, J. K., Doney, S. C., Glover, D. M. & Fung, I. Y.

Deep-Sea Res. I 49, 463-507 (2002). (c) Jickells, T. D. et al.

Science 308,

67-71 (2005). (d) Lam, P. J. & Bishop, J. K. B. Geophys. Res. Lett.

35, L07608

(2008). (e) Journet, E., Desboeufs, K. V., Caquineau, S. & Colin, J. L.

Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L07805 (2008).

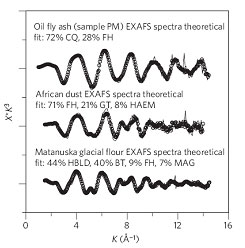

Aerosols often represent a majority of iron reaching the surface of the ocean,

yet relatively little is known about the processes that control their

solubility and fate in the environment. What is apparent is that aerosol source

regions can have widely different iron solubilities (up to three orders of

magnitude), and that differences in solubility are not simply a function of

iron concentration in the aerosol. The variable solubility of iron particulates

is a function of iron speciation, which is effectively measured using X-ray

absorption spectroscopy. Dusts derived from different locations have different

oxidation states, bonding environments and mineralogies, with each phase having

a distinct solubility (Figure 2). The fraction of soluble iron is highest in

aerosols from the fossil fuel combustion (oil fly ash). These materials contain

predominantly ferric iron, Fe(III), which is normally relatively insoluble, but

in this case, the iron is bound in sparingly soluble ferric sulfates. Aerosols

derived from the Saharan desert contain abundant insoluble iron(III) oxides,

including ferrihydrite, hematite and goethite, most of which do not dissolve in

ocean water. Glacial rock flour has intermediate solubility, with solubility

depending on the content of relatively reactive mixed valence silicates derived

from the physical weathering of rocks beneath the glaciers.

Figure 2.

Fits (open circles) of sample EXAFS spectra (lines) were determined by

least-squares fitting with combinations of spectra of known reference

materials. Standards consist of hornblende (HBLD), biotite (BT), ferrihydrite

(FH), magnetite (MAG), goethite (GT), hematite (HAEM) and coquimbite (CQ). The

error generated by SixPACK suggests that these fits are accurate within 5% for

each phase. The error for the relative abundance of goethite and ferrihydrite

in African dust is probably higher owing to similarities in structure and

associated XAS spectra of these two minerals.

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.