X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) will produce photon pulses with a unique and

desirable combination of properties. Their short X-ray wavelengths allow

penetration into materials and the ability to probe structure at and below the

nanometer scale. Their ultra-short duration gives information about this

structure at the fundamental time-scales of atoms and molecules. The extreme

intensity of the pulses will allow this information to be acquired in a single

shot, so that these studies can be carried out on non-repeatable processes or

on weakly-scattering objects that will be modified by the pulse. A fourth

property of XFEL pulses is their high transverse coherence, which brings the

promise of decades of innovation in visible optics to the X-ray regime, such as

holography, interferometry, and laser-based imaging. Making an effective use

of XFEL pulses, however, will benefit from innovations that are new to both

X-ray science and coherent optics. One such innovation is the new method of

time-delay X-ray holography [i], recently demonstrated at the FLASH FEL at DESY

in Hamburg, to measure the evolution of objects irradiated by intense pulses.

One of the pressing questions about the high-resolution XFEL imaging and

characterization of non-periodic or weakly-scattering objects is the effect of

the intense FEL pulse on the object, during the interaction with that pulse.

The method of single-particle diffraction imaging [ii] requires a stream of

reproducible particles (e.g. a protein complex or virus) inserted into the

beam, whereby a coherent X-ray diffraction pattern is recorded. The pulse will

completely destroy the object, but if the pulse is short enough the diffraction

pattern will represent the undamaged object. This ultrafast flash imaging was

demonstrated at the FLASH FEL using test objects that included microfabricated

patterns in silicon nitride foils [iii]. Those experiments showed that no

damage occurred during the 30 fs duration pulse. However, in those experiments

the imaging resolution was limited by the long 32 nm wavelength at which the

facility was then operating. We wished to dramatically increase our

sensitivity to the particles' explosions, to be able to increase the

understanding of the dynamics of particles and predict the imaging performance

at XFELs such as the LCLS. This was done in two ways in a single experiment:

by holographically measuring the time evolution of the particle at times after

the pulse had pass through the object; and by making an interferometric

measurement of the change in the optical path through the object. The

experimental technique, time-delay holography, achieved a time resolution

better than 3 fs, and a phase sensitivity of better than 3°, or a sensitivity

of < 3 nm of the expansion of the particles.

The idea behind time-delay holography is to use the same pulse that initiated

the interaction with an object to probe that object at a later time. This was

achieved simply by placing a mirror behind the object to send the pulse back on

the object a second time. The time delay is easily set by the distance between

the mirror and the object. This geometry is in fact the same as the

`dusty-mirror' experiment that was first carried out by Newton. Newton's

observations of light and dark rings formed when reflecting a shaft of sunlight

from a dusty mirror back through a hole in a screen, was one of the earliest

recorded of interference. The explanation for the effect was not forthcoming

until a century later when Thomas Young explained these as interferences of

waves traveling along two paths: 1) incident on the mirror, scattering from a

dust particle before passing through the mirror glass and reflecting its back

surface (which was silvered with mercury); and 2) first passing through the

thickness of the glass of the mirror, reflecting, and then scattering from the

particle on the way out. Further, experiments, performed with clouds of wig

powder, confirmed Young's hypothesis.

|

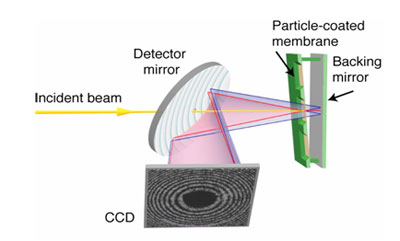

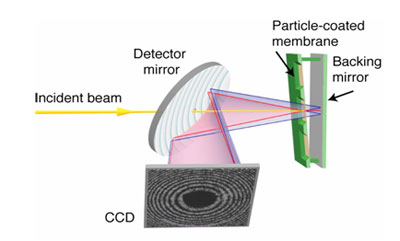

X-rays from the FLASH FEL are focused on to a 'dusty mirror' consisting of

particles on a membrane sandwiched closely to a multilayer backing mirror. An

ultrashort pulse hits the particles twice: on the way in and after reflecting

from the mirror. The two scattered waves interfere on the CCD to form a

hologram that encodes the change in the particle in the brief time that the

light was reflected back.

| |

We manufactured a multilayer with a broad reflectivity rocking curve to use as

the object backing mirror. Both the direct beam and the wide-angle scattered

wave from the object reflect from this mirror. The reflected direct beam, on

hitting the object for a second time, creates another scattered wave. This

wave, however, carries structural information about the object at a later time

than the initial interaction. If the object had expanded in this time, for

example, the second diffracted wave would be more forward-peaked. The two

scattered waves (the first from the undamaged object, the second a well-defined

time later) propagate together and are detected on a CCD. Now, even though the

pulse hit the object at two distinct times, the two waves generated by these

events do travel together and interfere with each other at the detector. This

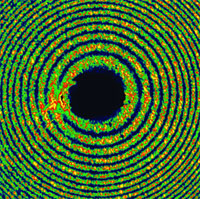

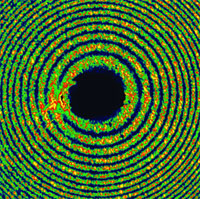

interference is dominated by a distinct ring pattern, which is the interference

of two spherical waves that are longitudinally displaced. With many objects

placed in the beam, each one generates an interference pattern which then

coherent adds with all others, modulating the ring pattern with a speckle

pattern. The ring pattern accurately encodes the distance between the

spherical waves, which can be determined to high accuracy. From this distance

the delay between the events can be determined to better than 3 fs.

The sample in our experiments consisted of an array of hundreds of silicon

nitride membrane windows on which 140-nm diameter polystyrene spheres were

placed. This was sandwiched against the multilayer backing mirror, positioned

with a slight wedge to be able to vary the delay simply by moving to different

membrane windows. The smallest gap was about 50 micron, to give a delay of

about 300 fs, and the longest gap gave a delay of 8 ps. Each window gave the

opportunity for several separate exposures. Even though the 20-micron-wide

focused FEL pulse ablated a crater in the backing mirror and melted a hole in

the silicon nitride, the entire window did not shatter so we could simply move

to a new spot.

We consider the recorded diffraction pattern as a hologram, as it consists of

the interference of a known reference wave (the undamaged object) with an

unknown object wave (the object undergoing an explosion). The holograms were

initially analyzed by considering the intensity of the interference between

these waves as a function of scattering angle, or momentum transfer q. This

was compared with calculated patterns, using a hydrodynamic model [iv]. We see

that, as predicted, the patterns become narrower and more forward peaked as the

time delay is increased beyond 3.8 ps. This suggests that in real space the

objects are indeed expanding following the interaction. Furthermore, the

evolution of the structure factor of the polystyrene sphere is in good

agreement with our calculations to the longest-measured delays of 8 ps where

the sphere has approximately doubled in size.

|

|

|

A time-delay hologram recorded for a delay of 348 fs for 140-nm diameter

polystyrene spheres. The ring pattern encodes both the delay and the change in

phase of the pulse as it travels through the exploding object. Holograms

recorded at different delays reveal the FEL-induced explosion of the spheres.

|

At delays shorter than 3 ps the expansion of the sphere was less than the

transverse spatial resolution of 60 nm and hence could not be observed.

However, changes in the optical properties of the sphere could be observed for

delays even shorter than 1 ps. This is due to the interferometric nature of

the measurement. The wave scattering from a polystyrene sphere is phase

shifted by an amount that depends on the sphere's refractive index and (at low

q) its thickness. If these properties change by the time the pulse returns to

the sphere then the phase shift on scattering the second time will be different

to the first. This relative phase shift will cause a change in the ring fringe

pattern of the hologram. For example, a change in the phase shift by

p (half a

wave) would reverse the contrast of the fringes by causing constructive

interference where there would have been destructive interference. The

relative phase can thus be determined from the positions of the ring maxima and

minima. We observed an increase in the phase shift with time delay and for

increasing pulse fluence. At a delay of 350 fs the change in phase shift was

equivalent to an increase of the optical path by less than 1/50th of a

wavelength. Since the refractive index is negative (and close to unity) this

corresponds to a reduction of material projected through the ball as would

occur if the sphere expanded in all directions by 3 nm.

The experiment achieved this high level of precision in space and time without

any complex optics or diagnostics, simply by utilizing the coherence of the

pulse and the geometry of the `dusty mirror.' Other geometries are planned in

for future X-ray FELs, using grazing geometries for shorter X-ray wavelengths

and shorter time delays. The technique should be applicable to the

high-resolution measurement of shocks, crack formation, ablation, melting,

ultrafast phase transitions, and plasma formation.

Acknowledgments

Experiments were carried out at the FLASH FEL in DESY, Hamburg, by a

collaboration of scientists from LLNL, Uppsala University, SLAC, LBNL, and TU

Berlin. This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of

Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract

DE-AC52-07NA27344.

Primary Citation

H. N. Chapman, S. P. Hau-Riege, M. J. Bogan, S. Bajt, A. Barty, S. Boutet, S.

Marchesini, M. Frank, B. W. Woods, W. H. Benner, R. A. London, U. Rohner, A.

Szöke, E. Spiller, T. Möller, C. Bostedt, D. A. Shapiro, M. Kuhlmann, R.

Treusch, E. Plönjes, F. Burmeister, M. Bergh, C. Caleman, G. Huldt, M. M.

Seibert and J. Hajdu, "Femtosecond Time-Delay X-ray Holography",

Nature 448, 676 (2007)

References

i. H.N. Chapman et al., "Femtosecond time-delay x-ray holography," Nature

448, 676-679 (2007).

ii. R. Neutze, R. Wouts, D. van der Spoel, E. Weckert, and J. Hajdu, "Potential

for biomolecular imaging with femtosecond x-ray pulses," Nature 406,

753-757 (2000).

iii. H.N. Chapman et al., "Femtosecond diffractive imaging with a soft-x-ray

free-electron laser," Nat. Phys.,2, 839-843 (2006).

iv. S.P. Hau-Riege, R.A. London, H.N. Chapman, and M. Bergh, "Soft-x-ray

free-electron-laser interaction with materials," Phys. Rev. E 76, 046403

(2007).

|

| PDF

Version | | Lay Summary | |

Highlights Archive

|

| SSRL is supported

by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL

Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy,

Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes

of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology

Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |

|