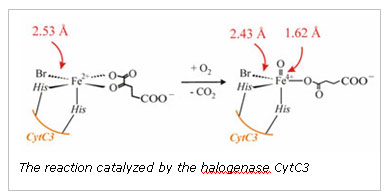

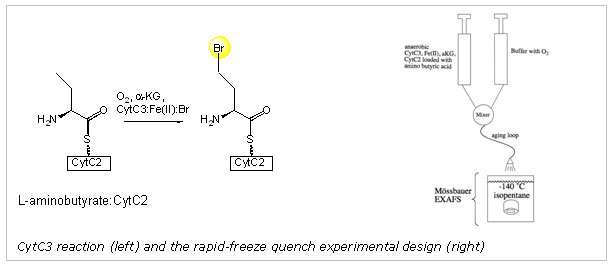

In the present study, X-ray absorption spectroscopy and Mössbauer spectroscopy

were used to identify the structural features consistent with the mechanistic

model, i.e. the presence of a short Fe(IV)-oxo interaction and a metal bound

halide. The Mössbauer spectra collected prior to XAS data collection

demonstrated that the quenched samples contained ~80% of the Fe(IV)

intermediate. Our XAS spectrum of the intermediate showed a large enhancement

in the 1s->3d transition pre-edge intensity relative to the anaerobic, reduced

control, which is consistent with the presence of an asymmetrical Fe(IV)=

O2- unit. The XANES edge energy is consistent with the 80% Fe(IV):

20% Fe(II) composition determined using Mössbauer spectroscopy. The most

compelling evidence for the presence of a formal Fe(IV)=O2- species

comes from the fitting analysis of the EXAFS oscillations. Fits to the

Fourier-filtered data require a short, 1.62 (± 0.02) Å Fe-O interaction to best

model the data. Furthermore, a large scatterer is apparent in the Fourier

transformation of the data. This peak can be modeled with an Fe-Br interaction

at 2.43 Å. If the coordination number of the short Fe-O interaction and the

Fe-Br interactions are systematically varied, the optimal coordination number

is 0.7-0.8 for both features, matching the sample composition determined by

Mössbauer spectroscopy. In contrast, fits to the reduced control sample were

not improved by adding a short Fe-O interaction. The Fe-Br interaction in the

control is 2.53 Å, consistent with the distance found in the crystal structure

of SyrB2. The structural features we identified using XAS are only consistent

with a Br-Fe(IV)=O2- unit and confirms a key component of the proposed

mechanism.

Primary Citation

References

There are over 4,500 known halogenated natural products. The presence of a

halogen in the molecular framework tunes a compound's chemical reactivity or

biological activity in these natural fungicides and antibiotics. Four classes

of enzymes are now known to catalyze halogenation reactions: 1) vanadium

haloperoxidases, 2) heme haloperoxidases, 3) flavin-dependent halogenases, and

4) non-heme iron, alpha-ketoglutarate (aKG) dependent

halogenases.1,2 Walsh and

coworkers first identified the

aKG dependent

oxygenases in 20053 and noted that they catalyze the insertion of

halides into unreactive substrates (for example, the chlorination of a terminal

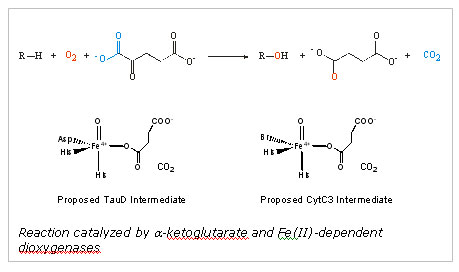

methyl group in barbamide4). The chemical logic of the non-heme

iron halogenases follows that of the aKG dependent,

non-heme iron dioxygenases such as TauD, the E. coli enzyme catalyzing

the hydroxylation of taurine (2-amino-1-ethanesulfonic acid).

5,6

For TauD, a high valent Fe(IV)-oxo species is generated that abstracts a

hydrogen atom from the substrate and a subsequent radical rebound results in

the hydroxylation of the substrate.7-9 A conserved His-His-Asp/Glu

"facial triad" provides the iron ligands.

Key insight into the mechanistic differences and similarities of the

aKG-dependent halogenases and oxygenases came from

the crystal structure of the halogenase SyrB2, responsible for the

chlorination reaction in the synthesis of syringomycin, a compound secreted by

Pseudomonas syringae.10 The structure indicated that a

halogen (Br or Cl) directly binds to the iron in place of the conserved

Asp/Glu. Thus, when a ferryl-oxo intermediate is generated upon

decarboxylation of the bound aKG, the intermediate

abstracts a hydrogen atom from the substrate and a halogen radical is

transferred to the substrate radical. Using the halogenase CytC3, an enzyme

capable of halogenating L-aminobutyrate, the Bollinger, Krebs, and Walsh groups

verified a key component of these proposed mechanistic steps. They

demonstrated that a high valent iron intermediate accumulates when the

halogenase CytC3 is exposed to oxygen in the presence of Cl-, aKG, and the

scaffold enzyme CytC2-substrate complex.11 They furthermore demonstrated that

this Fe(IV) species was indeed responsible for hydrogen atom abstraction from

the substrate.

Galonic Fujimori, D., Barr, E. W., Matthews, M.L., Koch, G. L., Yonce, J. R.*,

Walsh, C. T., Bollinger, J. M., Jr., Krebs, C., Riggs-Gelasco, P. J.

"Spectroscopic Evidence for a High-Spin Br-Fe(IV)-Oxo Intermediate in the

a-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Halogenase CytC3 from

Streptomyces", 2007, J. Am.

Chem. Soc., 129, 13408-13409.

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.