Nanometer-size metal particles are of fundamental interest for their chemical

and quantum electronic properties, and of practical interest for many potential

applications [1, 2]. Historically gold

nanoparticles are the best studied, dating back to ancient Rome where colloidal

gold was thought to have medicinal properties due to its blood red color. Gold

has proven to have applications in medicine with some modern arthritis drugs

using gold compounds. With all this interest in gold particles the structure

of a thiol-protected gold nanoparticle had yet to be unambiguously determined.

Electron microscopy

Nanometer-size metal particles are of fundamental interest for their chemical

and quantum electronic properties, and of practical interest for many potential

applications [1, 2]. Historically gold

nanoparticles are the best studied, dating back to ancient Rome where colloidal

gold was thought to have medicinal properties due to its blood red color. Gold

has proven to have applications in medicine with some modern arthritis drugs

using gold compounds. With all this interest in gold particles the structure

of a thiol-protected gold nanoparticle had yet to be unambiguously determined.

Electron microscopy

| |

|  |

|

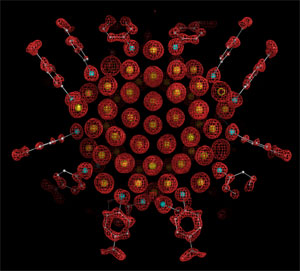

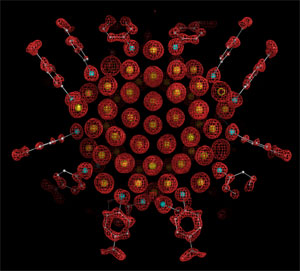

Fig. 1. X-ray crystal structure determination of Au102

(p-MBA)44

nanoparticle. Electron density map (red mesh) and atomic structure (gold atoms

depicted as yellow spheres, p-MBA shown as framework and small spheres sulfur

in cyan, carbon in gray and oxygen in red). [full-sized view] |

| [3,4],

powder x-ray diffraction [5] and theoretical studies

[6] had led to the

idea that gold nanoparticles would adopt closed geometric shells with

crystalline packing. This would lead to defined core sizes such that the gold

clusters would have a discrete number of atoms representing closed geometric

shells [7]. For example icosahedrally packed gold clusters were predicated to

have "magic number" sizes corresponding to 55, 147, 309. An alternative to the

closed geometric model was the jellium model, which predicted closed electronic

shells instead of geometric shells (reviewed in Rev. Mod. Phys 65, 611-676).

Testing of these theories requires the unambiguous structural determination of

a series of gold nanoparticles.

Structural determination of thiol protected gold nanoparticles has been

complicated by the problem that particles are typically heterogenous as

synthesized. Through systematic variation of solution conditions for gold

nanoparticle synthesis, the Kornberg lab obtained particles sufficiently

uniform in size for the growth of large single crystals opened the way to X-ray

structure determination. SSRL beamlines 11-1 and 11-3 were utilized to perform

X-ray analysis of these crystals resulting in the first unambigous

determination of a thiol protected gold nanoparticle. The resulting electron

density map revealed a particle of 102 gold atoms and 44 p-mercaptobenzoic

acids (p-MBAs) (Figure 1). The structure was refined at a resolution of 1.15

Å to Rwork and Rfree of 8.8% and 9.5%.

|  |

|

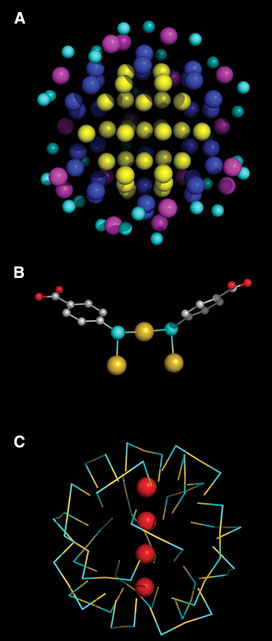

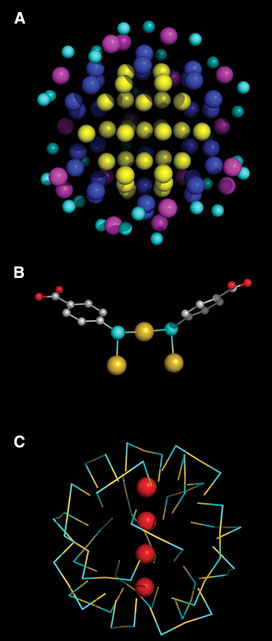

Fig. 2. Sulfur-gold interactions in the surface of the nanoparticle.

(A) Successive shells of gold atoms, interacting with zero (yellow), one

(blue), or two (magenta) sulfur atoms. Sulfur atoms are cyan. (B) Example of

two p-MBAs interacting with three gold atoms in a bridge conformation, here

termed a "staple motif." Gold atoms are yellow, sulfur cyan, oxygen red.

(C)

Distribution of staple motifs in the surface of the nanoparticle. Staple

motifs are depicted symbolically, with gold in yellow and sulfur in cyan.

Only the gold atoms on the axis of the MD are shown, in red. |

|

The Au102(p-MBA)44 structure revealed a metallic gold

nucleus of 79 atoms packed with decahedral symmetry protected by a

Au23(p-MBA)44 layer of gold-thiol oligomers. Gold atoms

up to 5.5 Å from the center of the particle do not contact sulfur, those in a

shell of radius 6.0 to 6.3 Å bind one sulfur, and those in a shell of radius

7.5 to 8.0 Å bind two sulfurs (Fig. 2A). All sulfur atoms lie in a shell of

radius 8.3¬ ± 0.4 Å and bind in a bridge conformation [8] to

two gold atoms, at least one of which binds two sulfurs, forming a "staple"

motif (Fig. 2B, C). The gold-sulfur distance ranges from 2.2 to 2.6 Å.

Gold-sulfur-gold angles are 80 to 115° and sulfur-gold-sulfur angles are 155 to

175°. If the surface is taken as all gold atoms interacting with sulfur, then

the coverage by p-MBA (thiol:gold ratio) is 70%, much higher than the values of

31% and 33% for benzenethiol [9] and alkanethiols [10] on Au(111) surfaces, reflecting the curvature of the

nanoparticle surface.

The very existence of a discrete Au102(p-MBA)44

nanoparticle is a notable finding from this work. Discrete sizes have been

explained in the past by geometrical or electronic shell closing. The

arrangement of gold atoms, with polar caps and an equatorial band, argues

against geometrical shell closing. If, however, each gold atom

(5d10 6s1)

contributes one valence electron, and 44 are engaged in bonding to sulfur, then

58 electrons remain, corresponding to a well-known filled shell. Indeed, a

naked cluster in the gas phase containing 58 gold atoms shows exceptional

stability [11, 12].

There are a number of connections of the Au102 nanoparticle

structure with previous work. First, structures of small gold, silver, and

platinum clusters, and of large platinum-palladium clusters, include five-fold

symmetry elements and also, in one case, thiols bridging between pairs of gold

atoms [13-16]. Second, electron

microscopy, X-ray powder diffraction and theoretical studies of large gold

clusters have given results consistent with a decahedron [3-

13]. Third,

theoretical studies have raised the possibility of distinct gold-sulfur units

capping a central gold core [17]. Fourth, the Face centered cubic (fcc)

packing in the core, with a gold-gold distance of 2.8-3.1 Å, corresponds with

the fcc packing in bulk metallic gold, with a gold-gold distance of 2.9 Å.

Fifth, the staple motif, containing alternating gold and sulfur atoms,

resembles the gold-thiol polymers believed to represent intermediates in the

process of nanoparticle formation [18]. Finally, circular dichroism

measurements on gold nanoparticle preparations have shown chiro-optical

activity [19].

We have screened fifteen crystals derived from multiple gold nanoparticle

preparations and obtained the same gold-102 structure. Other nanoparticle

preparations, however, which have also given rise to large single crystals,

will doubtless reveal other core structures, from which rules or principles of

core assembly may ultimately be derived. It remains to investigate the

chemical and physical properties of the Au102 nanoparticle, as well

as to explore the theoretical basis of the gold packing and gold-thiol

interactions we have observed.

Primary Citation

Jadzinsky, P.D., G. Calero, C. J. Ackerson, D. A. Bushnell and R. D. Kornberg,

Structure of a Thiol Monolayer-Protected Gold Nanoparticle at 1.1 Å Resolution.

Science, 2007. 318, p. 430-433.

References:

-

Brust, M. and C.J. Kiely, Monolayer protected clusters of gold and silver.

Colloids and Colloid Assemblies, 2004: p. 96-119.

-

Daniel, M.-C. and D. Astruc, Gold nanoparticles: assembly,

supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications

toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology. Chemical reviews, 2004.

104(1):

p. 293-346.

-

Yacaman, M.J., et al., Structure shape and stability of nanometric

sized particles. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B-an International

Journal Devoted to Microelectronics and Nanometer Structures-Processing

Measurement and Phenomena, 2001. 19(4): p. 1091-1103.

-

Ascencio, J.A., et al., Structure determination of small particles by

HREM imaging: theory and experiment. Surface Science, 1998. 396(1-3): p.

349-368.

-

Cleveland, C.L., et al., Structural Evolution of Smaller Gold

Nanocrystals: The Truncated Decahedral Motif. Physical Review Letters, 1997.

79(10): p. 1873-1876.

-

Aiken, J.D. and R.G. Finke, A review of modern transition-metal

nanoclusters: their synthesis, characterization, and applications in

catalysis.

Journal of Molecular Catalysis a-Chemical, 1999. 145(1-2): p. 1-44.

-

Martin, T.P., Shells of atoms. Physics Reports-Review Section of

Physics Letters, 1996. 273(4): p. 199-241.

-

Bau, R., Crystal Structure of the Antiarthritic Drug Gold Thiomalate

(Myochrysine): A Double-Helical Geometry in the Solid State. Journal of the

American Chemical Society, 1998. 120(36): p. 9380-9381.

-

Wan, L.J., et al., Molecular Orientation and Ordered Structure of

Benzenethiol Adsorbed on Gold(111). J. Phys. Chem. B, 2000. 104(15): p.

3563-3569.

-

Vericat, C., M.E. Vela, and R.C. Salvarezza, Self-assembled monolayers

of alkanethiols on Au(111): surface structures, defects and dynamics. Physical

Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2005. 7(18): p. 3258-3268.

-

de Heer, W.A., The physics of simple metal clusters: experimental

aspects and simple models. Rev. Mod. Phys., 1993. 65: p. 611-676.

-

Martin, T.P., et al., Shell structure of Clusters. J. Phys. Chem.,

1991. 95: p. 6421-6429.

-

Mednikov, E.G., M.C. Jewell, and L.F. Dahl, Nanosized

(m12-Pt)Pd164-xPtx

(CO)72(PPh3)20 (x approximately 7)

Containing Pt-Centered Four-Shell 165-Atom Pd-Pt Core with Unprecedented

Intershell Bridging Carbonyl Ligands: Comparative Analysis of Icosahedral

Shell-Growth Patterns with Geometrically Related

Pd145(CO)x(PEt3)30

(x approximately 60) Containing Capped Three-Shell Pd145 Core. J. Am.

Chem. Soc., 2007. 129: p. 11619-11630.

-

Shichibu, Y., Biicosahedral Gold Clusters

[Au25(PPh3)10(SCnH2n+1)5Cl2]2+ (n = 2-18): A Stepping Stone to

Cluster-Assembled Materials. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2007.

111(22): p. 7845-7847.

-

Teo, B.K. and H. Zhang, Synthesis and Structure of a Neutral

Trimetallic Biicosahedral Cluster,

(Ph3P)10Au11Ag12Pt2Cl7.

A Comparative Study

of Molecular and Crystal Structures of Vertex-Sharing Biicosahedral Mixed-Metal

Nanoclusters. Journal of Cluster Science 2001. 12(1): p. 349-383.

-

Teo, B.K. and e. al., Rotamerism and roulettamerism of vertex-sharing

biicosahedral supraclusters: Synthesis and structure of

[(Ph3P)10Au13Ag12Cl8](SbF6). Journal of Cluster Science 1993. 4(4):

p. 471-476.

-

Hakkinen, H., M. Walter, and H. Gronbeck, Divide and protect: Capping

gold nanoclusters with molecular gold-thiolate rings. Journal of Physical

Chemistry B, 2006. 110(20): p. 9927-9931.

-

Templeton, A.C., W.P. Wuelfing, and R.W. Murray, Monolayer-Protected

Cluster Molecules. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2000. 33(1): p. 27-36.

-

Schaaff, T.G. and R.L. Whetten, Giant Gold-Glutathione Cluster

Compounds: Intense Optical Activity in Metal-Based Transitions. Journal of

Physical Chemistry B, 2000. 104(12): p. 2630-2641.

|

| PDF

Version | | Lay Summary | |

Highlights Archive

|

| SSRL is supported

by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL

Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy,

Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes

of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology

Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |

|

Nanometer-size metal particles are of fundamental interest for their chemical

and quantum electronic properties, and of practical interest for many potential

applications [1, 2]. Historically gold

nanoparticles are the best studied, dating back to ancient Rome where colloidal

gold was thought to have medicinal properties due to its blood red color. Gold

has proven to have applications in medicine with some modern arthritis drugs

using gold compounds. With all this interest in gold particles the structure

of a thiol-protected gold nanoparticle had yet to be unambiguously determined.

Electron microscopy

Nanometer-size metal particles are of fundamental interest for their chemical

and quantum electronic properties, and of practical interest for many potential

applications [1, 2]. Historically gold

nanoparticles are the best studied, dating back to ancient Rome where colloidal

gold was thought to have medicinal properties due to its blood red color. Gold

has proven to have applications in medicine with some modern arthritis drugs

using gold compounds. With all this interest in gold particles the structure

of a thiol-protected gold nanoparticle had yet to be unambiguously determined.

Electron microscopy