We have demonstrated flash diffractive imaging of nanostructures using pulses

from the first soft-X-ray free-electron laser in the world, FLASH. This is the

first step in the development of single-molecule diffractive imaging (Neutze

et al., Nature, 406, pp. 752-757, 2000), where atomic-resolution

images of macromolecules will be obtained, without the need for crystallization

of the molecules.

As reported in the December issue of Nature Physics, we used an intense,

ultrafast pulse from the FLASH soft-X-ray free-electron laser to record a

coherent X-ray diffraction pattern from a nanoscale object. We inverted this

pattern to form a high-resolution image of the object, without the need for any

lenses, using the Shrinkwrap algorithm (Marchesini et al, Phys Rev

B, 68, 140101(R) 2003). The flash image resolves 50 nm features,

was recorded in 25 fs, and is the fastest image ever recorded with sub-optical

resolution. The 25 fs pulse contained about 1012 photons and was

focused down onto the sample to give an intensity of 4x1013

W/cm2, at a wavelength of 32 nm. The coherent diffraction pattern

was obtained before the sample exploded at a temperature of 60,000 K. No

evidence of sample damage could be seen in the reconstructed image.

We measured the diffraction pattern with a sensitivity of single photon

detection, even though the sample radiates after explosion and the intense

pulse vaporizes anything else in its path. This was achieved with a novel

diffraction camera consisting of a graded multilayer mirror which varies in

period by a factor of two across its face. The direct beam passed through a

hole in the mirror, while the coherent scattering from the sample was reflected

by the mirror onto a CCD. The mirror efficiently filtered out radiation of

other wavelengths and radiation travelling in the wrong direction (i.e. not

emanating from the sample).

Today, the bottleneck in the atomic resolution imaging of large macromolecules

and macromolecular complexes is a fundamental need for crystals. This limits

the scope of detailed structural analysis to molecules and assemblies which can

be crystallized. Many biologically important target complexes are difficult or

impossible to crystallize. There is, therefore, a great need to develop new

structural determination methods.

It was suggested by Neutze et al. (Nature, 406, 752-757, 2000)

that ultrafast pulses from a free-electron laser could be intense enough to

give a measurable diffraction pattern from a single uncrystallized

macromolecule. The incident X-ray dose would exceed the usual tolerance of

biological materials to keep their structural integrity, by five orders of

magnitude. In fact, the interaction with the pulse would be so violent that

the molecule would completely vaporize. However, due to the inertia of the

atoms, this damage process would not start until after the pulse had carried

away the information of the undamaged molecule.

To build up a three-dimensional image requires many coherent diffraction

patterns from many, identical, macromolecules. There are many challenges yet

to be addressed to carry out single-molecule imaging, such as delivering the

samples, orienting the diffraction data (or the molecules) and combining the

data. However, this current work gives great hope to the method, as it was

demonstrated that it is possible to record a diffraction pattern, with single

photon sensitivity, even when the illuminating pulse destroys everything in its

path, and turns the sample into a radiating plasma. The image was

reconstructed at the highest resolution consistent with the illumination and

collection aperture of the detector.

The experiments were carried out by a collaborative team from Lawrence

Livermore National Laboratory, the NSF Center for Biophotonics Science and

Technology, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, Uppsala University, the

Deutsches Elektronen-Synchroton (DESY), and Technische Universität Berlin. The

FLASH FEL began operations at DESY in August, 2005.

Primary Citation

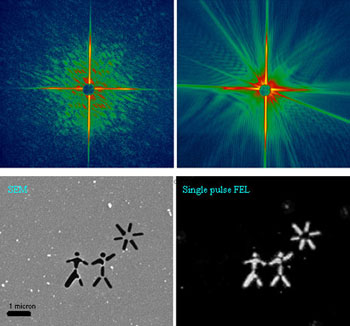

Top left: A diffraction pattern recorded with a single FLASH

FEL pulse from a test object placed in the focused beam. Top right: The

diffraction pattern recorded with the second pulse, showing diffraction from

the hole in the sample created by the first pulse. The sample was a pattern

milled from a 20-nm thick silicon nitride membrane, shown Bottom left.

Bottom right: The image reconstructed from the single-shot diffraction pattern

using our "Shrinkwrap" phase retrieval algorithm. The algorithm only used the

measured diffraction intensities and the knowledge that the diffraction pattern

was oversampled. We did not use the SEM image in the reconstruction.

H. N. Chapman, A. Barty, M. J. Bogan, S. Boutel, M. Frank, S. P. Hau-Reige, S.

Marchesini, B. W. Woods, S. Bajt, W. Henry. Benner, R. A. London, E. Plönjes,

M. Kuhlmann, R. Treusch, S. Düsterer, T. Tschentscher, J. R. Schneider, E.

Spiller, T. Möller, C. Bostedt, M. Hoener, D. A. Shapiro, K. O. Hodgson, D. van

der Spoel, F. Burmeister, M. Bergh, C. Caleman, G. Huldt, M. Seibert, F. R. N.

C. Maia, R. W. Lee, A. Szöke, N. Timneanu and J. Hajdu, "Femtosecond

Diffractive Imaging with a Soft-X-ray Free-Electron Laser", Nat. Phys.

Published online: 12 November 2006 | doi:10.1038/nphys461

| SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |