Copper is a

required micronutrient for all living cells, being an essential component of

many metalloenzymes, but free intracellular copper is highly toxic. Because of

this copper within cells is very tightly controlled, with specific copper ion

pumps (both importers and exporters) located at the cell surface, which are

coupled to highly specific metallochaperones that act as molecular taxi-cabs,

transporting copper to the active sites of particular target proteins [1]. The expression of the copper homeostatic apparatus is also

very tightly controlled, and is very sensitive to copper levels. In bacteria,

two families of copper-responsive transcriptional

repressors have been described; these are typified by the CueR repressor in

| |

Figure 1: Mycobacterium tuberculosis

| |

Escherichia coli [2], and the CopY repressor in

Enterococcus hirae [3].

However, many bacteria, including important human pathogens, such as

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Figure 1) and Listeria monocytogenes,

contain

neither family, and the mechanism of copper regulation in these organisms has

been unknown. The discovery of the CsoR repressor from M. tuberculosis

represents the first example of a totally new family of bacterial repressors

that appears to be more widespread than either of the two established repressor

families.

|  | |

|

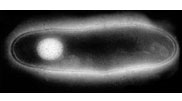

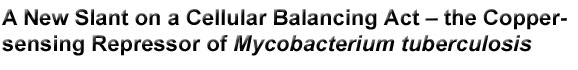

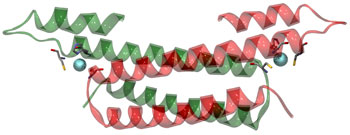

Figure 2: Crystal structure of the CsoR homodimer. The metallic atoms

indicate cuprous ions. [large view]

| | |

In the presence of copper the CsoR repressor dissociates from the cso operon

which can then be expressed. The operon contains the gene for what is believed

to be a cellular copper exporter - CtpV [4]. Binding of Cu(I)

to the CsoR dimer is thought to cause a conformational change, [effecting

decreased] CsoR affinity for DNA, allowing expression of the cso operon, thus

providing a protective mechanism against toxic levels of copper within cells.

The binding of copper to CsoR is exceptionally strong (KCu ≥ 10-19M), which is expected for a system that is

critical for removal of toxic copper from cells. While CsoR binds two Cu(I) per

homodimer only one copper is required to dissociate it from DNA. Liu et

al used a series of techniques to understand the structure of the Cu(I)

bound CsoR repressor. Protein crystallography of Cu(I)-bound CsoR indicates

that CsoR is an alpha-helical dimer, with each protomer composed of three

helices (Figure 2). The copper is bound between the two subunits, coordinated

by the side chains of amino acids from each subunit (Cys36, Cys65˙, and

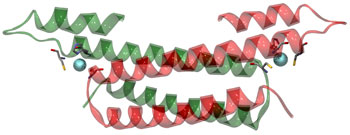

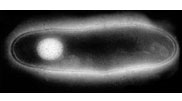

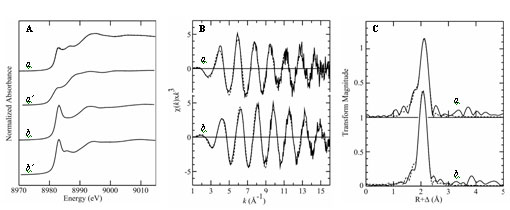

His61˙). Copper K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was used to provide

accurate bond-length information on the copper site of Cu(I)-bound CsoR. XAS

experiments were conducted on SSRL's structural molecular biology XAS beamline

9-3, with additional (preliminary) data being measured on the Canadian Light

Source HXMA beamline. Analysis of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure

(EXAFS) oscillations indicated a three-coordinate site with two Cu-S ligands at

2.21 Å and one oxygen or nitrogen at 2.06 Å. Analysis of the Cu XAS of the

Cu(I)-CsoR H61A mutant indicated a two-coordinate site with two sulfurs at 2.14

Å (Figure 3).

|  | |

|

Figure 3: XAS spectra of wild-type CsoR (a) and H61A mutant CsoR (b). A

shows the near-edge spectra compared with those of three-coordinate models (a'

and b', respectively), B shows the EXAFS oscillations and C shows the EXAFS

Fourier transforms (Cu-S phase-corrected). In B and C the solid lines show

experimental data, while the broken lines show the best-fit.

| | | |

Sequence comparisons indicate that homologues of

CsoR are very widespread in prokaryotes, being present in all major classes of

eubacteria. The study of Liu

et al thus represents a structural and functional characterization of the first

known member of a new and widely-distributed family of prokaryotic copper

regulators. The presence of CsoR is likely to enhance the survival of

M. tuberculosis in the host, and whether CsoR can be exploited as the basis for

new treatments for tuberculosis awaits future research.

Primary Citation

Liu, T., Ramesh, A., Ma, Z., Ward, S. K., Zhang, L., George, G. N., Talaat, A.

M., Sacchettini, G. C., Giedroc, D. P. "CsoR is a novel Mycobacterium

tuberculosis copper-sensing transcriptional regulator". Nature Chem.

Bio., 2007, 3, 60-68

References

-

Rae, T.D., Schmidt, P.J., Pufahl, R.A., Culotta, V.C. & O'Halloran,

T.V. Science 1999, 284, 805-808.

-

Strausak, D. & Solioz, M. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 8932-8936.

-

Stoyanov, J.V., Hobman, J.L. & Brown, N.L. Mol. Microbiol. 2001,

39,502-511.

-

Palmgren, M.G. & Axelsen, K.B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1365,

37-45

|

| PDF

Version | | Lay Summary | |

Highlights Archive

|

| SSRL is supported

by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL

Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy,

Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes

of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology

Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |

|