Though life on earth is composed of a diverse range of organisms, some with

many different types of tissues and cells, all these are encoded by a molecule

we call DNA. The information required to build a protein is stored in DNA

within the cells. Not all the message in the DNA is used in each cell and not

all the message is used all the time. During cell differentiation, the cells

become dedicated for their specific function which involves selectively

activating some genes and repressing others. Gene regulation is an important

event in the developmental biology and the biology of various diseases, but a

more complex process.

Though life on earth is composed of a diverse range of organisms, some with

many different types of tissues and cells, all these are encoded by a molecule

we call DNA. The information required to build a protein is stored in DNA

within the cells. Not all the message in the DNA is used in each cell and not

all the message is used all the time. During cell differentiation, the cells

become dedicated for their specific function which involves selectively

activating some genes and repressing others. Gene regulation is an important

event in the developmental biology and the biology of various diseases, but a

more complex process.

In the bacteria there are distinct enzymes while one is capable of cleaving

DNA, the other protects DNA by modification. The complementary function

provided by the set of enzymes offers a defense mechanism against the phage

infection and DNA invasion. The incoming DNA is cleaved sequence specifically

by the class of enzymes called restriction endonuclease (REase). The host DNA

is protected by the sequence specific action of matching set of enzymes called

the DNA methyltransferase (MTase). The control of the relative activities of

the REase and MTase is critical because a reduced ratio of MTase/REase activity

would lead to cell death via autorestriction. However too high a ratio would

fail to provide protection against invading viral DNA. In addition a separate

group of proteins capable of controlling R-M proteins have been identified in

various restriction-modification (R-M) systems which are called C proteins

(Roberts et al., 2003).

A homolog of R-M C protein, named as C.BclI regulates the expression level of

M.BclI (methyltransferase) in E. coli differently. In the absence of

C.BclI, M.BclI was over-expressed and displayed relaxed specificity for

methylation of non-cognate (non-specific or less specific) sites. However, in

the presence of C.BclI and C box (the C.BclI binding sequence), the expression

level of M.BclI was down regulated and M.BclI did not show relaxed specificity.

| |

|

|

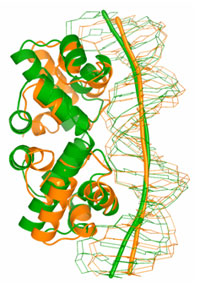

Figure 1

Dimer of C.BclI structure. Two molecules that form the dimer are related by a

2-fold rotational symmetry. There are five alpha helices (A, B, C, D, E) in

each monomer of C.BclI and of them HTH motif is formed by the helices B and C.

|

Balendiran's group at City of Hope collected the x-ray diffraction data on

BL1-5 at SSRL. The crystal structure of C.Bcll was determined to 1.8 Å

resolution by anomalous dispersion methods, using mercury derivatives. The

high-resolution crystal structure of C.BclI uncovers the presence of a

helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif (Figure 1) and the potential to bend B-DNA around

the C.BclI dimer (Figure 2). Furthermore interactions with DNA are likely

mediated by residues on the surface of the HTH motif helices between 34 and 48

in the structure. Moreover by analogy to known proteins with HTH motif

(Hochschild et al., 1983; Bushman

and Ptashne, 1988; Bushman et al., 1989) highly conserved residue Glu27

in the C family of proteins and partly conserved Asp31 residue in C.BclI may

play a crucial role in the interaction with RNA polymerase and be important for

transcriptional control.

|

|

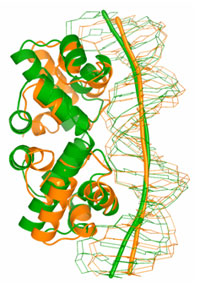

Figure 2

Comparison of C.BclI structure with the known structures containing HTH motif.

Induced DNA bending.

|

Primary Citation

Sawaya, M. R. Zhu, Z., Mersha, F., Chan, S-h., Dabur, R., Xu, S-y., Balendiran,

G. K., Crystal structure of the restriction-modification system control element

C.BclI and mapping of its binding site. Structure 13:1837-1847,

(2005).

Acknowledgement

The study was conducted in collaboration with Shuang-yong Xu, Ph.D., senior

scientist, New England Biolabs, with assistance from Professor David Eisenberg,

Professor Richard Dickerson, Duilio Cascio Ph.D., Michael R. Sawaya, Ph.D.,

University of California at Los Angeles; Stanford Synchrotron Radiation

Laboratory and SSRL staff; Jim D'Aoust, Project Manager, Cyberinfrastructure

Partnership, San Diego Supercomputer Center; Richard Roberts, Ph.D., CSO, Nobel

laureate, and Elisabeth Raleigh Ph.D., research director, New England Biolabs

Inc.

References

-

Bushman, F. D., and Ptashne, M. (1988). Turning lambda Cro into a

transcriptional activator. Cell 54, 191-197.

-

Bushman, F. D., Shang, C., and Ptashne, M. (1989). A single glutamic acid

residue plays a key role in the transcriptional activation function of lambda

repressor. Cell 58, 1163-1171.

-

Hochschild, A., Irwin, N., and Ptashne, M. (1983). Repressor structure and the

mechanism of positive control. Cell 32, 319-325.

-

Roberts, R. J., Belfort, M., Bestor, T., Bhagwat, A. S., Bickle, T. A.,

Bitinaite, J., Blumenthal, R. M., Degtyarev, S., Dryden, D. T., Dybvig, K.,

et al. (2003). A nomenclature for restriction enzymes, DNA methyltransferases,

homing endonucleases and their genes. Nucleic Acids Res 31,

1805-1812.

|

| PDF Version | | Lay Summary

|

| Highlights

Archive |

|

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of

Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National

Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical

Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

|

|

|

Though life on earth is composed of a diverse range of organisms, some with

many different types of tissues and cells, all these are encoded by a molecule

we call DNA. The information required to build a protein is stored in DNA

within the cells. Not all the message in the DNA is used in each cell and not

all the message is used all the time. During cell differentiation, the cells

become dedicated for their specific function which involves selectively

activating some genes and repressing others. Gene regulation is an important

event in the developmental biology and the biology of various diseases, but a

more complex process.

Though life on earth is composed of a diverse range of organisms, some with

many different types of tissues and cells, all these are encoded by a molecule

we call DNA. The information required to build a protein is stored in DNA

within the cells. Not all the message in the DNA is used in each cell and not

all the message is used all the time. During cell differentiation, the cells

become dedicated for their specific function which involves selectively

activating some genes and repressing others. Gene regulation is an important

event in the developmental biology and the biology of various diseases, but a

more complex process.