For many people, arsenic is synonymous with poison, so it is perhaps a surprise

that some plants, such as the fern Pteris vittata (Figure 1) seem to

quite deliberately accumulate large amounts of it. What is more, the plant

converts it to the most toxic inorganic form known. How does it do this?

First some background; while there is some evidence that arsenic is required

for health [1], this is debatable. On the other hand, the

poisonous nature of arsenic compounds was understood by the ancient Greeks and

Romans, and it has been used throughout history as a homicidal and suicidal

agent. It is found in two environmentally common oxy acids; arsenous acid

(H3AsO3), and arsenic acid

(H3AsO4), whose salts are known as arsenites and

arsenates, respectively. Of these, the trivalent arsenic species are the most

toxic. The infamous agent of murder is arsenic trioxide (white arsenic or

As2O3), which is simply the (reputedly tasteless)

anhydride of arsenous acid.

|

|

|

Figure 1.

Pteris vittata sporophyte

|

The fern P. vittata takes up arsenate from soils [2],

transforms it to the more toxic arsenite [3], and stores it

within its tissues. Quite remarkable levels of arsenic can be accumulated - up

to 1 % dry weight. The plant, which presumably does this to prevent itself from

being eaten, is quite unaffected by its toxic cargo, and even seems to grow

slightly better in its presence. Pickering and co-workers have used X-ray

Absorption Spectroscopy Imaging, conducted on SSRL's BL9-3, to begin to unravel

how the fern carries out this fascinating process. Their technique

[4] combines X-ray absorption fluorescence microprobe maps

taken at carefully selected energies to yield beautiful images of the

distribution of the arsenic species in vivo.

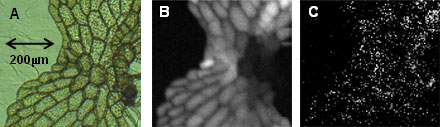

Since ferns have two distinct generations in their life cycle - the familiar

leafy sporophyte (Figure 1), and the sexually active but rather tiny

gametophyte - Pickering et al. investigated both generations. They found that

arsenate is transported through the vascular tissue from the roots to the

fronds (leaves), and only there is it reduced to arsenite and apparently stored

in the vacuole. Arsenic-thiolate species observed surrounding the veins in the

leaves may be intermediates in this reduction. Arsenic was found to be excluded

from reproductive areas (spores and sporangia), and concentrated within nearby

sterile hairs or paraphyses. Being only one cell thick, the gametophytes are

ideal for studying the arsenic distribution within cells. Pickering et al.

showed that arsenite is compartmentalized within the large central cell vacuole

(Figure 2). In the gametophyte arsenic was found to be excluded from cell

walls, rhizoids and reproductive areas.

|  | | |

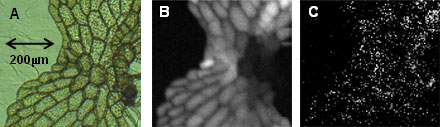

P. vittata gametophyte, optical micrograph (A) and XAS images of arsenite (B)

and arsenate (C), showing localization of arsenite in the large central cell

vacuole, and discrete speckles of arsenate are localized in unknown

sub-cellular compartments (possibly plant Golgi bodies).

| |

| | |

The study demonstrates the strength of the in situ capabilities of XAS

imaging by directly visualizing physiological processes in living plant

tissues. The study also provides insights which may prove useful for

phytoremediating arsenic-contaminated sites.

Primary Citation

Pickering, I.J., Gumaelius, L., Harris, H.H., Prince, R.C., Hirsch, G., Banks,

J.A., Salt, D.E., George, G.N. "Localizing the biochemical transformations of

arsenate in a hyperaccumulating fern". Environ. Sci. Technol.

,

2006, 40, 5010-5014.

References

-

Nielsen, F.H. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1990, 26-27, 599-611.

-

Ma L.Q.; Komar K.M.; Tu C.; Zhang W.; Cai Y.; Kennelley E.D. Nature

2001, 409, 579.

-

Webb, S.M.; Gaillard, J-F; Ma, L.Q.; Tu, C. Environ. Sci. Technol.,

2003, 37, 754-760.

-

Pickering, I.J., Prince, R.C., Salt, D.E., George, G.N. Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97, 10717-10722.

|

| PDF Version | | Lay Summary

|

| Highlights

Archive |

|

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of

Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National

Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical

Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

|

|

| Last

Updated: |

25 SEP 2006 |

| Content

Owner: |

Ingrid Pickering and Graham George, University of Saskatchewan

|

| Page

Editor: |

Lisa

Dunn |

|