Filamentous actin (F-actin), a biological rod-shaped protein, provides the

structural framework in living cells. The assembly and organization of F-actin

in vivo is controlled predominantly by actin binding proteins which locally

crosslink actin into a rich variety of phases, including bundles and networks.

Espins are one type of actin binding protein responsible for the formation of

large parallel actin bundles. Espin is found in actin bundles in sensory cell

microvilli, such as the stereocilia of cochlear hair cells. Within the cochlea

of the inner ear, sound waves cause the basilar membrane to vibrate. These

vibrations bend the stereocilia in the hair cells, which then trigger nerve

impulses that are transmitted to the brain. Genetic mutations in espin's

F-actin binding sites cause deafness. In this study crosslinked actin

structures formed by mutated espins were studied in order to look into the

potential link between the crosslinked bundle structure and deafness.

Filamentous actin (F-actin), a biological rod-shaped protein, provides the

structural framework in living cells. The assembly and organization of F-actin

in vivo is controlled predominantly by actin binding proteins which locally

crosslink actin into a rich variety of phases, including bundles and networks.

Espins are one type of actin binding protein responsible for the formation of

large parallel actin bundles. Espin is found in actin bundles in sensory cell

microvilli, such as the stereocilia of cochlear hair cells. Within the cochlea

of the inner ear, sound waves cause the basilar membrane to vibrate. These

vibrations bend the stereocilia in the hair cells, which then trigger nerve

impulses that are transmitted to the brain. Genetic mutations in espin's

F-actin binding sites cause deafness. In this study crosslinked actin

structures formed by mutated espins were studied in order to look into the

potential link between the crosslinked bundle structure and deafness.

The structure of and interactions between the normal and mutant espin-actin

complexes was systematically investigated using confocal microscopy and

synchrotron small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) performed at BL4-2 of the

Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory and at the BESSRC-CAT (BL12-ID) at

the Advanced Photon Source. The SAXS data shows how interactions between

F-actin and different espin linkers are expressed in the system's

self-assembled structure and phase behavior.

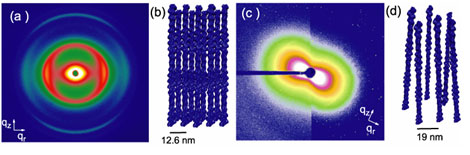

The mixtures of normal espin and F-actin showed well defined actin bundles in

the confocal microscope images, which were found to be extremely well ordered

hexagonal bundle of twisted actin filaments when studied via SAXS (Fig. 1).

From the diffraction data we also measured the twisting of the helical F-actin

filaments and found that it was increased by -0.9 degrees from the native

helical twisting of F-actin. This suggests that the bundles of twisted

filaments are under constant strain, which acts to maintain the stability of

the bundle structure. From the large number of and narrow width of the

hexagonally coordinated peaks we determined that these bundles were well very

ordered and large. This corresponds to very rigid bundles; an important factor

for bundles which are typically used as mechanical sensors (levers) in living

cells.

Fig. 1(a)

Diffraction from partially oriented F-actin-espin bundles shows many

hexagonally coordinated peaks. The reconstructed 3D bundle structure is

approximated in (b). (c) Diffraction from F-actin complexed with mutant espin.

The diffraction pattern only shows a "bow-tie" pattern which is indicative of a

liquid crystalline nematic phase, like that shown in (d). The mutant espins

only weakly crosslink the actin filaments, but the normal espins arrange the

actin into tight crystalline bundles.

The structure of the bundles changes dramatically when normal espin is replaced

with espin mutants that cause deafness. The deafness mutants have damaged actin

binding sites and thus can be thought of as being less 'sticky' than the wild

type espins. With these deafness mutations we could then assess the

relationship between linker 'stickiness' and actin bundle formation. Damaging

the actin binding site impairs the ability to form thick ordered bundles. The

dominant deafness mutant (which has one good actin binding site, and one

partial binding site) bundles actin at high espin concentrations creating a

similar hexagonal structure to the normal espin-actin bundles but the

inter-actin spacing was larger and more variable. At low espin concentrations,

though, the hexagonal bundle peaks decreased in intensity and a new

nematic-like peak appeared which displays a characteristic "bow-tie" pattern in

2D (Fig. 1). This indicates that the rods spontaneously oriented along an axis

but they only had short-range positional ordering, not like the bundles which

have long range ordering (Fig. 1). This nematic ordering is in addition to weak

crosslinking which pulls the actin filaments close together, but not close

enough to form bundles. A stronger mutant espin (which has only one actin

binding site, the second being completely truncated by the mutation) was also

studied, and for this recessive mutation, bundles never form, only the weakly

crosslinked nematic phase is observed.

The observation of this crosslinked nematic-network phase was very exciting

from a physics standpoint as new theories have been recently developed to

explain physical relationship between the network and bundle phases of actin

observed in cells, and the multitude of crosslinking proteins. By changing the

preferred orientation of the crosslinking protein (does it like to form bundles

or perpendicular networks) a rich phase behavior can predicted. However, the

weakly crosslinked nematic phase observed with the deafness mutant espins,

which are "weakly sticky" but still want to orient the actin filaments in

bundles, has not yet been explored theoretically. This suggests that there is a

new axis yet to be explored in the theoretical phase diagram of filaments and

crosslinkers - the 'stickiness' axis.

The biological implications of a weakly crosslinked nematic phase in ear cell

stereocilia show up predominantly in the bending stiffness. A weakly

crosslinked nematic phase has a bending stiffness which is about a thousand

times floppier, than a rigid bundle. This is in fact consistent with the

observation that mutant espin cause malformed, floppy stereocilia. A thinner

diameter bundle (which occurs even when the deafness mutant espins do bundle)

also results in much floppier bundles. As a consequence the ear cannot respond

to sound in the same way. When mixing mutant espin and normal espin (as is

normally the case for the dominant mutant expression in humans), however, the

bundling ability of the espin can be restored, and the bundles get slightly

thicker. It is possible that this mechanism could be used to potentially

'rescue' this particular kind of pathology, particularly in the dominant mutant

case, where partial expression of the normal espin is already possible. If gene

expression could turn on the production of slightly more normal espin linkers,

a kind of rescue attempt at restoring hearing could, in principle, be made.

Primary Citation

Kirstin R. Purdy, James R. Bartles, and Gerard C. L. Wong; "Structural

Polymorphism of the Actin-Espin System: A Prototypical System of Filaments and

Linkers in Stereocilia", Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 058105 (2007)

| SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |