Malaria is one of the most devastating parasitic diseases worldwide, amounting

to 300 to 500 million cases and ~2 million deaths per year (1). Multiple

species of Plasmodium infect the human host, the most important ones being

P. falciparum and P. vivax. Increased occurrence of

multi-drug resistant Plasmodium strains reflects the need for new effective

antimalarials. Human

infection starts when Anopheline mosquitoes inject sporozoites into the skin

during a blood meal. The sporozoites gain access to the blood stream and invade

liver cells where they develop and multiply. Upon rupture of the infected liver

cell, merozoites are released and rapidly enter red blood cells, where they

undergo schizogony (cell multiplication) and propagate the blood cycle of the

infection that causes the malaria symptoms (2).

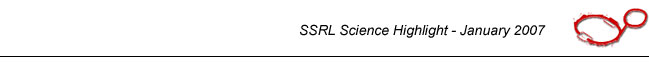

A multi-protein complex located in the narrow space between the parasite plasma

membrane and the microtubule-supported inner membrane complex empowers both

substrate-dependent gliding motility and host cell invasion in Plasmodium

(3).

This invasion machinery (Fig. 1) is highly conserved and required for leaving

and entering different types of host cells. Blocking one or more interactions

of the invasion machinery with small molecules inhibitors could provide

effective novel antimalarials. The current study provides atomic level insights

into a crucial protein interaction occurring in this essential multi-protein

assembly of the malaria parasite.

Using crystallographic data collected at SSRL beamline 9-2 and at the ALS, Wim

Hol's group have solved the structure of a complex of P. knowlesi

Myosin A-tail interacting protein (MTIP) and MyoA-tail to 2.6 Å

(P. knowlesi is a rodent

parasite. P. falciparum and P. knowlesi share 71% sequence

identity). The

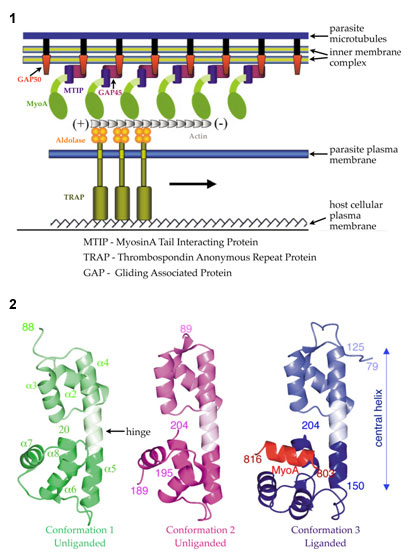

crystals belonged to space group P63 and contained 3 different conformations of

MTIP in the asymmetric unit with one subunit bound with MyoA-tail (Fig. 2). The

Myosin A-tail interacting protein bridges between the membrane associated

proteins GAP45/GAP50 and the C-terminal tail of Myosin, which interacts with

short actin filaments (Fig. 1). The actin filaments are attached to the

glycolytic enzyme aldolase, which needs to be multimeric to connect actin and

TRAP. TRAP recognizes specific host cell receptors on red blood cells

initiating the process of invasion (Fig. 1).

A combination of hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions is responsible for

forming the complex between the tail and the tail-binding protein (Fig. 2).

MyoA residues Gln-808 and His-810 make numerous hydrogen bonds with MTIP,

whereas electrostatic interactions mainly involve the first and third residues

from the conserved tribasic RKR motif spanning residues 812-814 in the

MyoA-tail. MyoA Arg-812 forms a salt bridge with MTIP Glu-180, whereas MyoA

Arg-814 is interacting with the side chain of MTIP Asp-202. Mutagenesis to Ala

of each of the two MyoA-tail Arg residues of the tribasic motif, and each of

the three hydrophobic MTIP-facing residues, results in a failure to interact

with MTIP, which is in complete agreement with the structure of the MyoA-MTIP

complex.

The viability as a drug target was tested by in vivo inhibition

experiments of P. falciparum cultures using the MyoA-tail. The binding

pocket for MyoA-tail provided by the C-terminal domain of MTIP displays

significant differences to the human homolog. These differences can be

exploited for structure based drug design of small molecules mimicking the

hydrophobic side chains of MyoA-tail yielding a higher binding affinity and

specificity.

This work was supported in part by NIH/NIGMS Grant 1P50 GM64655-01, Structural

Genomics of Pathogenic Protozoa and NIH Grant AI48226.

Primary Citation

References

Bosch, J., Turley, S., Daly, T. M., Bogh, S. M., Villasmil, M. L., Roach, C.,

Zhou, N., Morrisey, J. M., Vaidya, A. B., Bergman, L. W., et al. (2006).

Structure of the MTIP-MyoA complex, a key component of the malaria parasite

invasion motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 4852-4857

| SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. |