Christopher S.

Kim,1 James J. Rytuba,2 Gordon E. Brown, Jr.3

Christopher S.

Kim,1 James J. Rytuba,2 Gordon E. Brown, Jr.3

1Department of Physical Sciences, Chapman University, Orange, CA

92866

2U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA 94025

3Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford

University, Stanford, CA 94305

Introduction

| |

|

|

|

|

Figure 1.

Dr. Christopher Kim collects a mine waste sample from the Oat Hill mercury mine

in Northern California. The majority of mercury mine wastes at these sites are

present as loose, unconsolidated piles, facilitating the transport of

mercury-bearing material downstream into local watersheds.

|

|

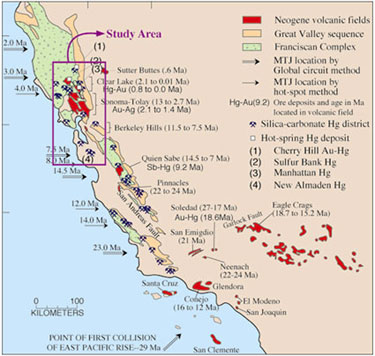

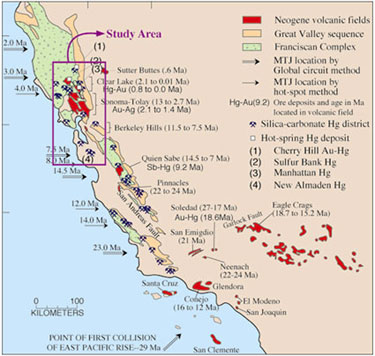

Mercury (Hg) is a naturally occurring element that poses considerable health

risks to humans, primarily through the consumption of fish which have

accumulated harmful levels of mercury in their tissue. This bioaccumulation of

mercury in fish is a result of elevated exposure from a number of sources

including industrial emissions, atmospheric deposition, and mercury-bearing

products such as thermometers, batteries, electrical switches, and fluorescent

light bulbs. In California, however, a significant amount of mercury enters

the environment through the dozens of mercury mines located throughout the

California Coastal Range (Figure 2), where thousands of tons of mercury were

recovered for use in gold recovery further east in the Sierra Nevada. The

transport of mercury from these remote poorly-monitored mine sites has resulted

in elevated mercury levels in more populated urban regions such as the San

Francisco Bay Area. Understanding the movement and geochemistry of mercury

from mines in California is therefore necessary in order to predict the

potential impacts and hazards associated with this form of mercury

contamination.

The speciation of mercury is a critical determinant of its mobility,

reactivity, and potential bioavailability in mercury- and gold-mine impacted

| |

|

|

|

|

Figure 2.

Geologic map of mercury mining areas in the California Coast Range,

distinguishing between silica-carbonate deposits and hot-spring Hg deposits.

Samples were primarily collected from a variety of mine waste media at multiple

sites in the outlined region. From Rytuba (12).

(click on image for larger view of map)

|

|

regions. Mercury speciation in these complex natural systems is additionally

influenced by a number of physical, geological, and anthropogenic variables. In

order to investigate the degree to which several of these variables may affect

mercury speciation, extended x-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS)

spectroscopy was conducted at SSRL beamlines 4-3 and 11-2 to determine the

mercury species and relative proportions of these species present in

mercury-bearing wastes from selected mine-impacted regions in California and

Nevada. This work represents the first in situ, non-destructive method by

which to identify mercury speciation in natural samples.

Mercury speciation protocol

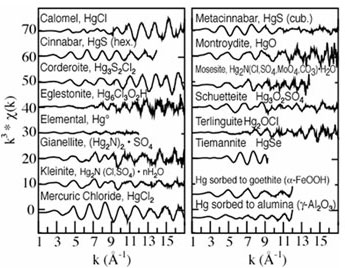

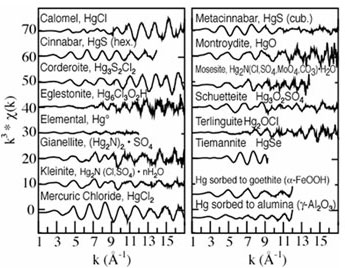

The EXAFS-based speciation procedure for Hg is similar to that previously

developed for and applied to other metal(loid)s such as arsenic

(1,2), lead

(3-5), and

zinc (6,7). It involves the

comparison of an EXAFS spectrum collected from a Hg-bearing sample with a

spectral library of model compounds previously generated from an assortment of

Hg minerals and sorbed species (Figure 3). While each model compound spectrum

serves as the spectral fingerprint of a single Hg species, the EXAFS spectrum

| |

|

|

|

|

Figure 3.

Mercury model compound database of a host of Hg minerals and sorbed species.

Each Hg LIII-edge EXAFS spectrum is distinct from the others, reflecting the

unique structural environment around Hg from phase to phase.

(click on image for larger view)

| |

|

of a heterogeneous natural sample represents a composite of the EXAFS

contributions from all detectable Hg species present. Therefore, an EXAFS

spectrum collected from a natural sample containing multiple Hg species can be

decomposed using a linear least-squares fitting method into the sum of its

individual components through direct comparison with the model compound

spectra. Furthermore, determining the relative proportion of each model

compound's contribution to the least squares linear combination fit directly

yields the molar percentage of the respective Hg species identified in the

sample.

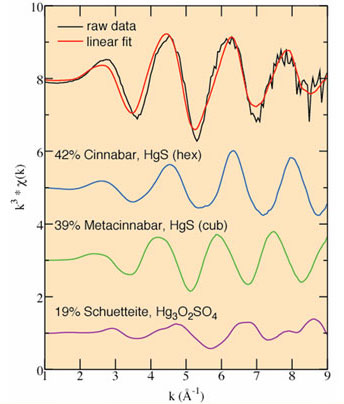

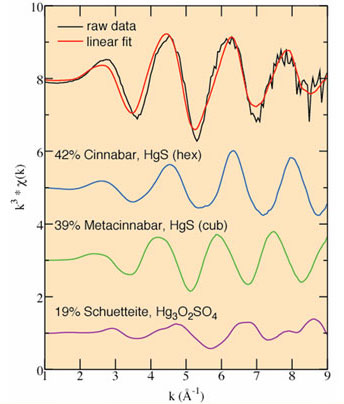

Figure 4 presents an example of such a linear fit, showing the fitted Hg

LIII-EXAFS spectrum of a Hg-bearing sample from the Bessels Mill in

Nevada and the related fit components. In this case, cinnabar (HgS, hex.),

metacinnabar (HgS, cub.), and schuetteite

(Hg3O2SO4) have been identified as

the significant components contributing to the final fit; when scaled to 100%,

they contribute in proportions of 42% and 39%, and 19%, respectively. This

identification of the relevant Hg species present and the proportions at which

they are present in the sample represents the formal, EXAFS-determined Hg

speciation of the sample. Application of the EXAFS technique to determine Hg

| |

|

|

|

|

Figure 4.

Linear fitting results for a sample from the Bessels Mill, Carson River, NV,

showing the raw data (top, in black) best linear combination fit (top, in gray)

and the components (below) of the linear fit, scaled to the proportions to

which they contribute to the fit.

|

|

speciation in calibrated mixtures of model Hg compounds (8) and a separate

comparison of results from EXAFS spectroscopy and sequential chemical

extractions on a selected suite of Hg-bearing samples (9) further validated the

use of EXAFS spectroscopy for determining Hg speciation in complex samples and

better defined its limitations, where fit components should be considered

accurate to ±25% of their stated value and fit components comprising less than

10% of a fit should be viewed with caution.

Sampling

Samples were collected from a number of inactive Hg mine sites located along

the California Coast Range Hg mineral belt. Hg-contaminated samples from

former gold mine workings were also collected from the Carson River basin in

western Nevada. The sampled media included calcines (roasted ore), condenser

soot, waste rock (unroasted low-grade Hg-bearing material), distributed

sediments, Hg-bearing gold mine tailings, and an amorphous Fe-oxyhydroxide

precipitate forming downstream from an acid mine drainage seep at a Hg mine.

Most samples contained Hg concentrations of 100 mg/kg (ppm) or greater,

although a few samples with Hg concentrations below 100 ppm were also

successfully analyzed using EXAFS spectroscopy.

Effect of Geological Background on Hg Speciation

Since Hg ore deposits are known to form in a variety of geological settings, a

comparison of Hg speciation in mine wastes between different ore depositional

environments was expected to reveal fundamental differences in the types of Hg

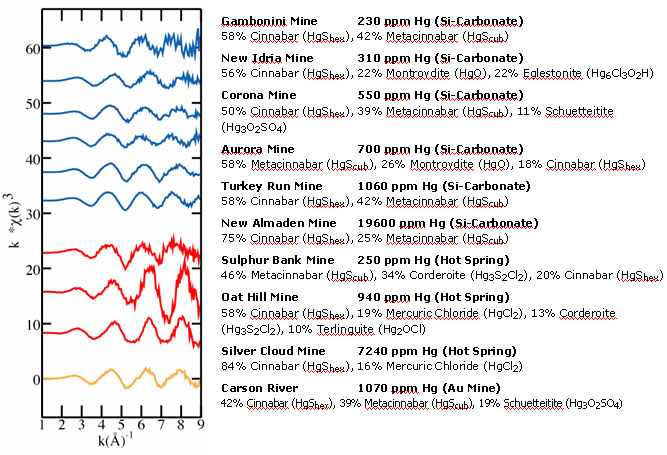

species present. Speciation results determined by EXAFS spectroscopy of

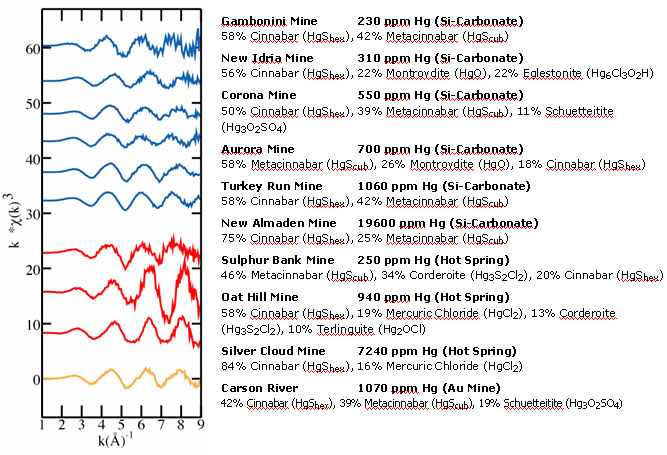

Hg-contaminated mine wastes from California and Nevada are shown in Figure 5.

Briefly, there are two primary types of Hg deposits in the California Coast

Range: (1) silica-carbonate Hg deposits, in which Hg is deposited in the highly

fractured zones of hydrothermally altered serpentinite bodies emplaced along

fault zones such as the San Andreas Fault, and (2) hot-spring Hg deposits,

where Hg is deposited in low-temperature, near-surface active hydrothermal

systems enriched in chloride and sulfate (10).

|

|

Figure 5.

Summarized linear fitting results for a variety of Hg-bearing mine wastes, with

original EXAFS spectra shown.

|

The majority of Hg in all samples was found by EXAFS analysis to be present as

Hg-sulfides, either as cinnabar or metacinnabar; this finding is common to

nearly all global Hg deposits. Corderoite

(Hg3S2Cl2), a Hg-sulfide-chloride, was also

observed in two samples from hot-spring Hg deposits. In addition, minor

proportions of non-Hg-sulfide species, including as mercuric chloride

(HgCl2), eglestonite (Hg6Cl3O2H),

montroydite (HgO), schuetteite (Hg3O2SO4), and

terlinguite (Hg2OCl), were identified in several samples. The high

solubility of many of these species compared to the extremely insoluble

Hg-sulfides suggests that, although comprising a smaller percentage of the

total Hg in the sample, these species may be disproportionately larger

contributors of ionic Hg to the surrounding environment.

The influence of the Hg depositional environment on Hg speciation in mine

wastes is demonstrated by the consistent presence of Hg-chloride species in

samples collected at hot-spring Hg deposits, and their relative absence in

samples collected at silica-carbonate Hg deposits. Some exceptions exist, such

as the presence of eglestonite in the New Idria sample, although this could be

due to overprinting of a silica-carbonate Hg deposit with later hot-spring

hydrothermal systems. Nevertheless, based on the range of samples analyzed, a

general distinction in Hg speciation can be observed, with the presence of

Hg-chloride species as the primary difference between the two deposit types.

This implicates hot-spring Hg deposits as sites of higher priority for

remediation and introduces a new level of sophistication for such

prioritization, as speciation can now be considered alongside total Hg

concentration.

Effect of Ore Roasting on Hg Speciation

| |

|

|

|

|

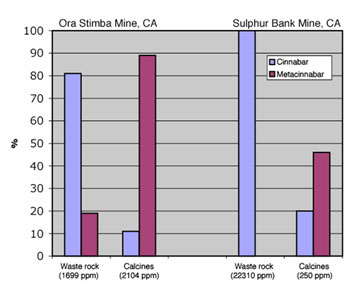

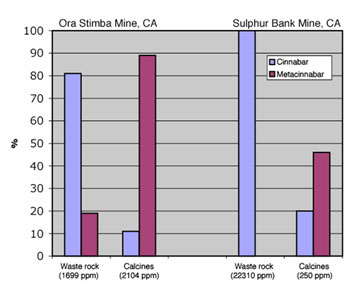

Figure 6.

Hg speciation of calcine and waste rock samples from two separate mines,

showing a distinct shift between the proportions of cinnabar (HgS, hex) and

metacinnabar (HgS, cub) as a result of roasting.

|

|

As seen, Hg-sulfides in the form of cinnabar and metacinnabar constitute the

highest proportion of Hg-containing species in Hg mine wastes, consistent with

the fact that cinnabar is the primary ore mineral in Hg deposits. However, the

proportions of metacinnabar detected in several roasted samples (Figure 5),

sometimes as high as 58%, are much greater than anticipated based on field

studies of Hg ore deposits, which only rarely report minor amounts of

metacinnabar. The transformation of cinnabar to metacinnabar during the

roasting process is a likely explanation for the elevated metacinnabar levels

detected in these calcines. Figure 6 shows Hg speciation results for

Hg-bearing mine wastes from the Sulphur Bank and Ora Stimba mines in

California. At both mines, a calcine pile and (unroasted) waste rock pile were

sampled to assess potential effects of ore roasting on Hg speciation. The

results show that cinnabar is the dominant Hg species in the unroasted waste

rock samples (present in proportions from 81-100%), while metacinnabar is more

prevalent in the calcines (46-81%). This suggests that ore roasting converts

cinnabar to metacinnabar by heating it above the cinnabar-metacinnabar

inversion temperature of 345° C (11). During the

mining process, Hg ore was crushed and then roasted in excess of 600°C to

release Hg as volatile elemental Hg° gas (12),

thereby providing temperatures sufficient to cause the conversion of

non-released cinnabar to metacinnabar. Such a process may also have introduced

impurities such as Fe, Se, and Zn that impeded the conversion back to cinnabar

upon cooling and are more common to the metacinnabar

structure (13,14). The

higher solubility of metacinnabar compared with cinnabar indicates that

calcines are of greater concern for cleanup than waste rock.

Effect of Particle Size on Hg Speciation

Particle size can exhibit a governing influence on factors such as the

concentration, speciation, solubility, and mobility of heavy metals in

contaminated wastes. The dependence of total Hg concentration and speciation on

particle size in Hg mine wastes was explored by collecting samples from

different Hg mines and separating them by dry sieving into a number of discrete

size fractions. Hg speciation of selected size fractions was then determined

using EXAFS spectroscopy (15).

| |

|

|

|

|

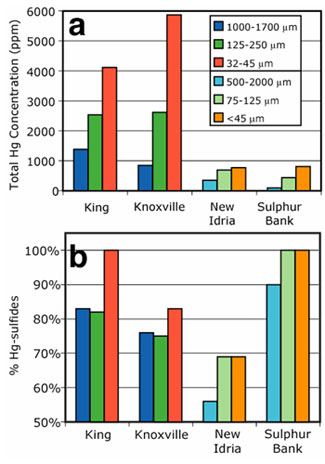

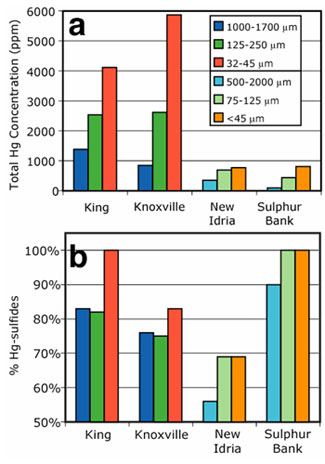

Figure 7.

(a) Total Hg concentration of various sieved size fractions from different Hg

mine calcines as determined by cold vapor atomic fluorescence spectroscopy

(CVAFS). (b) Percent Hg-sulfides as determined by EXAFS spectroscopy of

various sieved size fractions from different Hg mine calcines.

|

|

Hg total concentration and selected speciation results of these size fractions

are shown in Figure 7. As particle size decreases within each bulk sample the

total Hg concentration increases (Figure 7a), in some cases by nearly an order

of magnitude (e.g., a calcine from the Sulphur Bank mine shows an

increase in Hg concentration from 97 ppm in the 500-2000 µm size fraction

to 810 ppm in the <45 µm size fraction). This trend agrees with other

studies (16,17) which showed

elevated concentrations of Hg-sulfides in very fine sand and silt fractions

among Hg-mine wastes in northern California and Alaska. In addition to total

Hg concentration, EXAFS analysis reveals that the relative proportions of

Hg-sulfides (cinnabar, metacinnabar, and corderoite) in the sieved fractions of

calcines also increase with decreasing particle size (Figure 7b), although this

trend is less pronounced than that of total Hg concentration, increasing

between 8-18% among the samples studied.

These trends may be linked to the low solubility and hardness of cinnabar and

metacinnabar. As Hg-sulfides feature Ksp values in the range of 10-36

(18) and hardness levels of 2.5-3 (19), physical weathering (i.e. abrasion, fracturing, and

disaggregation) may exceed chemical weathering, (i.e. dissolution) under

certain conditions; furthermore, Hg-sulfides should weather at more rapid rates

than the quartz, silicates, and metal oxides that comprise the bulk of most

sample matrices. Mechanical weathering therefore likely yields the observed

enrichment in total Hg as particle size decreases. Additionally, with

decreasing particle size the increased available surface area of soluble Hg

minerals such as Hg-chlorides, oxides, and sulfates would facilitate the

dissolution of these species, resulting in the greater proportions of

relatively insoluble Hg-sulfides observed in the finest-grained fractions. A

study of Hg speciation in stream sediments of the Almadén cinnabar mining

region in Spain described a similar relationship between the proportion of Hg

present as Hg-sulfides and total Hg concentration (20). The combined results

of these studies indicate that these trends are common in cinnabar mine

environments.

The interested reader is referred to a comprehensive review of Hg speciation in

mining environments recently published by C. Kim (21) for more information and

details about the EXAFS speciation technique.

Primary Citation:

C. S. Kim, J. J. Rytuba and G. E. Brown, Jr., "Geological and

Anthropogenic Factors Influencing Mercury Speciation in Mine Wastes: an EXAFS

Spectroscopy Study", Appl. Geochem. 19, 379 (2004)

References:

-

A. L. Foster, G. E. Brown, Jr., T. Tingle, G. A. Parks, Am. Mineral. 83, 553-568 (1998).

-

K. S. Savage, T. N. Tingle, O. D. PA, G. A. Waychunas, D. K. Bird, Appl.

Geochem. 15, 1219-1244 (2000).

-

J. D. Ostergren, G. E. Brown, Jr., G. A. Parks, T. N. Tingle, Environ.

Sci. Technol. 33, 1627-1636 (1999).

-

G. Morin, J. D. Ostergren, F. Juillot, P. Ildefonse, G. Calas, G. E. Brown,

Jr., Am. Mineral. 84, 420-434 (1999).

-

A. Manceau, M. C. Boisset, G. Sarret, J. L. Hazemann, M. Mench, P. Cambier, R.

Prost, Environ. Sci. Technol. 30, 1540-1552 (1996).

-

A. Manceau, B. Lanson, M. L. Schlegel, J. C. Harge, M. Musso, L. EybertBerard,

J. L. Hazemann, D. Chateigner, G. M. Lamble, Am. J. Sci.

300, 289-343 (2000).

-

F. Juillot, G. Morin, P. Ildefonse, T. P. Trainor, M. Benedetti, L. Galoisy, G.

Calas, G. E. Brown, Jr., Am. Mineral. 88, 509-526 (2003).

-

C. S. Kim, G. E. Brown, Jr., J. J. Rytuba, Sci. Total Environ.

261, 157-168 (2000).

-

C. S. Kim, N. S. Bloom, J. J. Rytuba, G. E. Brown, Environ. Sci.

Technol. 37, 5102-5108 (2003).

-

J. J. Rytuba, W. R. Miller, USGS Circular C1103-A, 90-91 (1994).

-

G. Kullerud, Carnegie I. 64, 194-195 (1965).

-

J. J. Rytuba, Sci. Total Environ. 260, 57-71 (2000).

-

F. W. Dickson, G. Tunell, Am. Mineral. 44, 471-487 (1959).

-

V. L. Tauson, V. V. Akimov, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61,

4935-4943 (1997).

-

C. S. Kim, J. J. Rytuba, G. E. Brown, Jr., Applied Geochemistry

19, 379-393

(2004).

-

J. B. Harsh, H. E. Doner, J. Environ. Qual. 10, 333-337 (1981).

-

H. Nelson, B. R. Larsen, E. A. Jenne, D. H. Sorg, Science 198, 820-824 (1977).

-

G. Schwarzenbach, M. Widmer, Helv. Chim. Acta 46, 2613-2628 (1963).

-

C. Klein, C. S. Hurlbut, Jr., Manual of Mineralogy (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

New York, NY, ed. 20th, 1985).

-

R. C. R. Martin-Doimeadios, J. C. Wasserman, L. F. G. Bermejo, D. Amouroux, J.

J. B. Nevado, O. F. X. Donard, J. Environ. Monit. 2, 360-366

(2000).

-

C. S. Kim, in Mercury: Sources, Measurements, Cycles and Effects. J. B.

Percival, Ed. (Mineral. Assoc. Canada, Short Course, 2005), vol. 34, pp.

95-122.

|

| PDF Version | | Lay Summary

|

| Highlights

Archive |

|

SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of

Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National

Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical

Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

|

|

Christopher S.

Kim,1 James J. Rytuba,2 Gordon E. Brown, Jr.3

Christopher S.

Kim,1 James J. Rytuba,2 Gordon E. Brown, Jr.3