Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by low bone mass, leading to an increased risk for fracture. Current treatment costs are in the tens of billions per year in the United States and are expected to grow. A factor in bone fractures is damage accumulation. Microdamage occurs in bone tissue through activities of daily living, reducing the tissue’s strength, stiffness and energy dissipation properties [1]. Damage is believed to stimulate bone remodeling and new bone formation. Diseases such as osteoporosis alter bone remodeling and may weaken the tissue.

X-ray negative stains have been used to examine microdamage in cortical and cancellous bone; however, evaluation methods have used scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or micro-computed tomography (microCT) with either a surface or low resolution analysis, respectively [2, 3]. By combining x-ray negative stains with transmission x-ray microscopy (TXM) at SSRL, nanoscale full-field transmission images of microdamage with 30 nm resolution have been obtained for the first time.

The study, recently published in PLoS ONE by scientists and engineers from Cornell University, the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and SSRL, examined nanoscale damage morphologies in cortical bone and illustrated nanoscale damage formation mechanisms. Bone beams were created from sheep bones, and damage created by applying either a monotonic or fatigue (for 20,000 cycles) load. Samples were stained with lead-uranyl acetate to indicate damage, and sectioned to 50 micron thickness. Samples were imaged using TXM at Beam Line 6-2 at SSRL. Samples were also imaged with traditional microCT to compare stain presence at lower resolution.

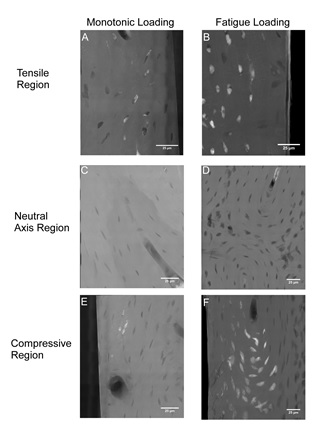

Increased staining was present with fatigue loading as compared to monotonic loading. In both cases staining was localized to existing bone structures, and limited new surfaces were created (Figure 1). At lower resolutions, these bone structures are not discernible and damage is manifested diffusely, which may in fact reflect this damage to bone structures. The initiation of bone damage within existing bone structures provides new insights into damage propagation and fracture of bone.

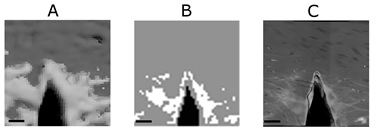

Damage visualized by TXM and microCT illustrated important differences between the methods (Figure 2). Damaged regions appeared larger in microCT images than in TXM images due to partial volume effects with microCT. MicroCT analyses of microdamage may, therefore, overestimate the damage present.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine bone damage at the nanoscale using projection imaging in cortical bone. The insights from this study illustrate that damage originated and propagated in the cell cavities and processes rather than creating new surfaces within the tissue. This knowledge lends new insights into skeletal damage mechanisms and future avenues for research.

- D. B. Burr, “Microdamage and Bone Strength”, Osteoporosis Int. 14, S67 (2003)

- S. Y. Tang, D. Vashishth, “A Non-invasive in vitro Technique for the Three Dimensional Quantification of Microdamage in Trabecular Bone”, Bone 40, 1259 (2007)

- M. B. Schaffler, W. C. Pitchford, K. Choi, J. M. Riddle, “Examination of Compact Bone Microdamage Using Back-scattered Electron Microscopy”, Bone 15, 483 (1994)

G. R. Brock, G. Kim, A. R. Ingraffea, J. C. Andrews, P. Pianetta, and M. C. H. van der Meulen, "Nanoscale Examination of Microdamage in Sheep Cortical Bone Using Synchrotron Radiation Transmission X-ray Microscopy", PLoS ONE 8, e57942 (2013) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057942