Mercury in the environment can easily reach toxic levels. In a process called methylation, Hg is transformed into a form that can be accumulated in the muscle and fatty tissue of fish. Accumulated levels of methylmercury become higher as the fish grow, and levels are magnified up the food web as larger fish eat smaller fish, a process called biomagnification. As a result, mercury concentrations in fish can be millions of times higher than in surrounding waters [1]. Fish advisories have been set to limit consumption of certain fish higher up on the food web, especially for pregnant women and small children (see Figure 1).

Mercury in the environment can easily reach toxic levels. In a process called methylation, Hg is transformed into a form that can be accumulated in the muscle and fatty tissue of fish. Accumulated levels of methylmercury become higher as the fish grow, and levels are magnified up the food web as larger fish eat smaller fish, a process called biomagnification. As a result, mercury concentrations in fish can be millions of times higher than in surrounding waters [1]. Fish advisories have been set to limit consumption of certain fish higher up on the food web, especially for pregnant women and small children (see Figure 1).

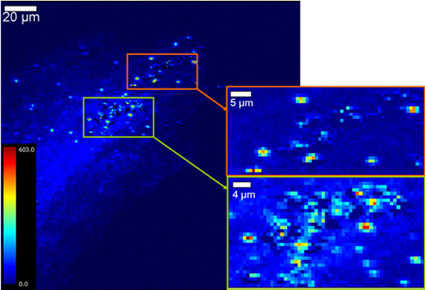

The team collected S. foliosa and S. alterniflora plants from two locations in SF Bay and studied their native Hg levels, as well as their capacity for Hg uptake. Using Hg L3 XANES collected on Beam Lines 9-3 and 10-2 they determined the overall chemical speciation, or forms, of Hg within the plants and their root zones. Scanning x-ray fluorescence (XRF) and micro-XANES on Beam Line 2-3 were utilized to map the location, distribution, and speciation of Hg within the plant roots, which appeared in concentrated spots (Figure 2).

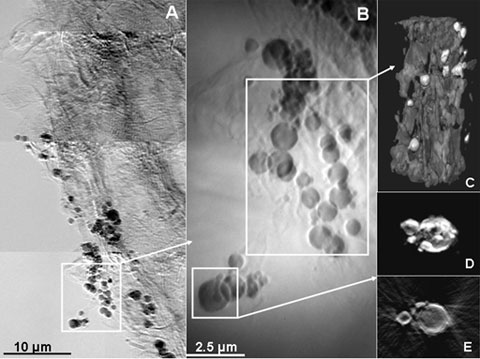

Using transmission x-ray microscopy (TXM) on Beam Line 6-2c, it was apparent from 2D images at 40 nm resolution and 3D tomography that the concentrated spots seen with XRF were associated with microorganisms (probably SRB) in which most of the Hg was accumulated within cell walls (Figure 3). Combining data from all techniques used, TXM results indicated that Hg was most likely bound to sulfur in plant roots and microbial walls, presumably transferred to the SRB cytoplasm after methylation. Some Hg also precipitated as metacinnabar (HgS) as part of this process.

In summary, the use of X-ray microscopy combined with Hg L3 XANES has permitted us to obtain a "snapshot" of mercury methylation and metacinnabar precipitation in S. foliosa and S. alterniflora. This "snapshot" of Hg methylation in progress provides insight into the spatial and biochemical relationships between SRB and Spartina roots, revealing areas of Hg concentration within both. Although we found that the native S. foliosa has the capability for greater Hg uptake, perhaps due to its longer adaptation to the Hg-contaminated area; total Hg concentrations are the same in both species in the field, indicating that there is no significant difference in the amount of methylmercury that would be produced by each species. Although concentrations in the field average 0.1 ppm for both Spartina species, these are dominant florae within SF Bay and other locations. If an average of 10% of this Hg is methylated, Spartina must be carefully considered for its role in mercury methylation in the SF Bay estuarine ecosystem. This work has been published in Environmental Science and Technology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Opp for her help in statistical treatment of the Hg uptake data; and Sam Webb, Sean Brennan, Jennifer Cassano, and Sarah Hayes for their help with data collection. A. Kahn and B. Mooney were supported by awards from the CSU East Bay Associated Students, and CSU East Bay provided support to J. C. Andrews. SSRL is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The transmission x-ray microscope is supported by NIH/NIBIB grant number 5R01EB004321.

The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

- Wiener JG, Krabbgenhoft DP, Heinz GH, Scheuhammer AM (2003). Ecotoxicology of mercury. In Handbook of Ecotoxicology; Hoffman DJ, Rattner BA, Burton GA Jr, Cairns J Jr, Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL; pp 409-463.

- Benoit JM, Gilmour CC, Heyes A, Mason RP, Miller CL (2003) Geochemical and biological controls over methylmercury production and degradation in aquatic ecosystems. In Biogeochemistry of Environmentally Important Trace Elements; Chai Y, Braids OC, Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC; pp 262-297.

- Ayres DR, Smith DL, Zaremba K, Klohr S, Strong DR (2004) Spread of exotic cordgrasses and hybrids (Spartina sp.) in the tidal marshes of San Francisco Bay, California, USA. Biol. Invas. 6, 221-231.

Patty C, Barnett B, Mooney B, Kahn A, Levy S, Liu Y, Pianetta P, Andrews JC (2009) Using X-ray Microscopy and Hg L3 XANES to study Hg Binding in the Rhizosphere of Spartina Cordgrass. Environ Sci Technol 43: 7397-7402.