Porphyrins have earned the title "pigments of life" (1) because they are essential for all life on planet earth. Porphyrins are the precursors of heme, chlorophyll, and cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12). Heme is an iron-coordinated porphyrin and serves as a prosthetic group in several proteins to mediate catalysis (cytochromes, peroxidases) or recognize diatomic molecules like oxygen (globins), carbon monoxide (CO) (cytochrome oxidase), and nitric oxide (NO) (soluble guanylyl cyclase) (2,3). With the exception of a few microorganisms, heme is found in all three archaea, prokarya, and eukarya kingdoms (2). On the one hand, heme biosynthesis is a sine qua non for the function of heme-containing enzymes and proteins. For example, gaseous messengers like NO cannot be biosynthesized in humans without the heme-containing enzyme nitric oxide synthase (4). On the other hand, enzymatic degradation of heme results in the generation of CO - a key cellular signal generated as a by product of heme oxygenase chemistry.

Porphyrias are a group of inborn errors of heme biosynthesis that are designated as hepatic or erhthropoietic based on clinical manifestation and the primary site in which the enzymatic defect manifests (5). For example, the penultimate step of the heme biosynthesis involves the enzyme protoporphyrinogen oxidase. Defects in this enzyme lead to variegate porphyria and roughly 10,000 South Africans suffer from this disease. Based on genealogical evidence it has been shown that this disease was inherited from a single individual - a woman who emigrated from the Netherlands in 1688. As a result, all the South African families with variegate porphyria exhibit the same substitution (R59W) in the protoporphyrinogen oxidase gene (6). The madness suffered by King George III (1738 - 1820) has also been attributed to hereditary porphyria (7).

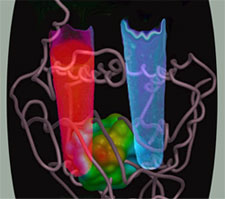

Hereditatry coproporphyria (HCP) is an autosomal dominant acute hepatic porphyria with incomplete penetrance due to half-normal activity of coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPO) (8) Defects in this enzyme result in acute attacks characterized by severe abdominal pain, hypertension, tachycardia, and neurologic dysfunction. In some cases skin photosensitivity is also seen. In the absence of prompt and appropriate treatment, HCP can very rapidly become a life-threatening medical emergency. CPO catalyzes the antepenultimate step in heme biosynthesis. First purified in the early 1960s, CPO mediates the oxidative decarboxylation of propionic acid side chains of rings A and B in coproporphyrinogen III without utilizing transition metals, reducing agents, thiols, prosthetic groups, organic cofactors, or modified amino acids (9). Whereas the stereochemistry of this reaction has been worked out, the molecular oxygen consumption poses an interesting chemical puzzle.

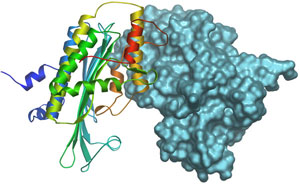

We have solved the crystal structure of human CPO at 1.58 Å resolution (Fig. 2) and show that it is a dimer in the native state (10). CPO has a novel tertiary topology with an unusually flat seven-stranded b-sheet surrounded by α-helices. To our great surprise, we found a molecule of citrate (tricarboxylate) tightly bound at the active site. By comparing the interaction of citrate in CPO and the structurally unrelated aconitase, we have identified the key catalytic residues. Furthermore, we have proposed two models for how this enzyme catalyzes the successive oxidative decarboxylation reactions. The first model involves a radical intermediate whereas as the second proceeds via carbanion formation.

This project was funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts via a Pew Scholar Award, the Robert A. Welch Foundation and by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports of the Czech Republic.

- Battersby AR, Fookes CJ, Matcham GW, McDonald E. Biosynthesis of the pigments of life: formation of the macrocycle. Nature. 1980 May 1;285(5759):17-21.

- Panek H, O'Brian MR. A whole genome view of prokaryotic haem biosynthesis. Microbiology. 2002 Aug;148(Pt 8):2273-82.

- Nioche P, Berka V, Vipond J, Minton N, Tsai A-L, Raman CS. Femtomolar Sensitivity of a NO Sensor from Clostridium botulinum. Science. 2004 Nov 306:1550-53.

- Raman CS, Martásek P, Masters BSS. Structural Themes Determining Function in Nitric Oxide Synthases. In The Porphyrin Handbook, Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, Eds. (New York: Academic Press), Vol 4: Biochemistry and Binding: Activation of Small Molecules pp. 293 - 340 (2000)

- Badminton MN, Elder GH. Molecular mechanisms of dominant expression in porphyria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(3):277-86.

- Meissner PN, Dailey TA, Hift RJ, Ziman M, Corrigall AV, Roberts AG, Meissner DM, Kirsch RE, Dailey HA. A R59W mutation in human protoporphyrinogen oxidase results in decreased enzyme activity and is prevalent in South Africans with variegate porphyria. Nat Genet. 1996 May;13(1):95-7.

- Cox TM, Jack N, Lofthouse S, Watling J, Haines J, Warren MJ. King George III and porphyria: an elemental hypothesis and investigation. Lancet. 2005 Jul 23-29;366(9482):332-5.

- Martasek P. Hereditary coproporphyria. Semin Liver Dis. 1998;18(1):25-32.

- Sano S, Granick S. Mitochondrial coproporphyrinogen oxidase and protoporphyrin formation. J Biol Chem. 1961 Apr;236:1173-80.

Lee DS, Flachsova E, Bodnarova M, Demeler B, Martasek P, Raman CS. Structural basis of hereditary coproporphyria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005 Oct 4;102(40):14232-7.