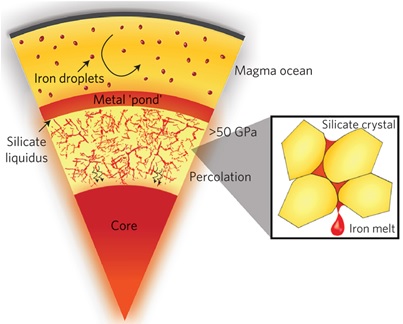

The formation of Earth’s metallic core, which makes up a third of our planet’s mass, represents the most significant differentiation event in Earth’s history. Earth’s present layered structure with a metallic core and an overlying silicate mantle would have required mechanisms to separate iron alloy from a silicate phase. Percolation of liquid iron alloy moving through a solid silicate matrix (much as water percolates through porous rock, or even coffee grinds) has been proposed as a possible model for core formation (Figure 1). Many previous experimental results have ruled out percolation as a major core formation mechanism for Earth at the relatively lower pressure conditions in the upper mantle, but until now experimental results at lower mantle conditions were not possible due to the ultrahigh pressures and temperatures required and the difficulty in analyzing the samples.

Figure 1. Model for iron and silicate in Earth’s core. Magma ocean and percolation might be dominant mechanisms over different pressure–temperature ranges during Earth’s core formation.

Scientists from Stanford University (C. Shi and W. L. Mao), the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research (Shanghai, China) and Carnegie Institute of Washington (Li Zhang, Wenge Yang, Junyue Wang), in close collaboration with SSRL (Y. Liu and J. C. Andrews), designed an experiment to study what happens to molten iron in silicates, at conditions mimicking those in Earth’s lower mantle. A laser-heated diamond anvil cell was used to create the immense pressures (up to 64 GPa, or 640 thousand times atmospheric pressure), and high temperatures (up to 3,300 K).

The researchers studied the laser-heated, pressure-treated particles applying state-of-the-art nanoscale synchrotron X-ray tomography at SSRL’s Beam Line 6-2. They observed for the first time and with unprecedented spatial resolution a change in the three-dimensional iron melt distribution as pressure increased, from isolated droplets at 25 GPa to an interconnected network at 64 GPa (Figure 2). These results provide evidence that percolation through such an interconnected network would be an efficient mechanism at Earth’s lower mantle conditions.

These findings have significant implications for the evolution of the planet, Earth’s early thermal history, and the large-scale geochemical distribution of elements. As Earth began to form and solidify and its internal pressure reached a critical value (above 50 GPa), percolation could become a dominant process. Thus, core formation in our planet may not be a single-stage process and could rather have occurred as a series of steps under evolving conditions. At lower pressure conditions, formation of a magma ocean may be the likely differentiation mechanism. Liquid metal would separate rapidly from liquid silicates and accumulate as a ponded layer at the base of the magma ocean. At much higher pressures, solid silicates could form an interconnected network allowing the molten iron to percolate through it and trickle down into Earth’s core.

Acknowledgments:

W.L.M. and C.Y.S. are supported by NSF-EAR-1055454. Portions of this work were performed at HPCAT (Sector 16), Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory. HPCAT operations are supported by DOE-NNSA under Award No. DE-NA0001974 and DOE-BES under Award No. DE-FG02-99ER45775, with partial instrumentation funding by NSF MRI-1126249. APS is supported by DOE-BES, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Portions of this research were carried out at the SSRL, a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Stanford University. HPSynC is supported by EFree, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES) under award number DE-SC0001057.

C. Y. Shi, L. Zhang, W. Yang, Y. Liu, J. Wang, Y. Meng, J. C. Andrews, W. L. Mao, “Formation of an Interconnected Network of Iron Melt at Earth’s Lower Mantle Conditions”, Nat. Geosci., Advance Online Publication 10/06/2013, DOI: 10.1038/ngeo1956