The manipulation of thin-film magnetic multilayers has been an active and technologically relevant area of research since the discovery of giant magnetoresistance in magnetic multilayers by Fert and Grünberg in 1988 [1, 2]. The design of such devices is made simpler by utilizing the intrinsic properties of the materials from which they are made. In this study Ni/Gd/Ni multilayers of varying thickness were grown by D.C. magnetron sputtering and measured by x-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) at a range of temperatures (6 K to room temperature) and a range of magnetic fields (± 250 mT).

XMCD allows the magnetic state of each element to be measured individually. Changing the energy of the incoming x-ray makes it possible to select which electrons in an energy level to excite. Since the energies of electron energy levels differ from element to element, one can choose an element to interact with. This powerful measurement technique allows for observations that would not be possible with conventional techniques.

The system measured is a thin-film multilayer with the structure Ni/Gd/Ni. Ni (nickel) is a transition-metal ferromagnet that remains magnetic far above room temperature. Gd (gadolinium) is a rare-earth ferromagnet that only stays magnetic at temperatures up to approximately room temperature. Within a ferromagnet, neighboring atoms prefer to align their magnetic moments. However, at the Ni/Gd interfaces in this sample, the neighboring Ni and Gd atoms would prefer to have their magnetic moments pointing in exactly opposite directions. This means that the preferred state of the system without any other influences is for all the Ni atoms’ moments to point in one direction, and all the Gd atoms’ moments to point in the opposite direction.

Under the influence of a magnetic field, however, the situation becomes more complicated. All atoms’ moments, both Ni and Gd, like to point in the same direction as the external magnetic field, an effect that increases with the strength of the applied field. But since both the Ni and Gd interface moments still want to point opposite to one another, there will be a competition between this interface effect and the applied magnetic field.

There are a number of factors that can affect this competition. Since the ferromagnetism in Ni and Gd disappears at different temperatures, it fades at different rates as the temperature is increased from 6 K (-267 degrees celsius, -449 fahrenheit). This affects how strongly Ni magnetic moments will align with other Ni magnetic moments, and the same for Gd. Another factor that will affect the competition is the thickness of the Ni and Gd layers. Since the competition arises due to the Ni and Gd alignment at the interface, as the layer thickness increases the effect the layer has on the overall behavior of the sample will decrease.

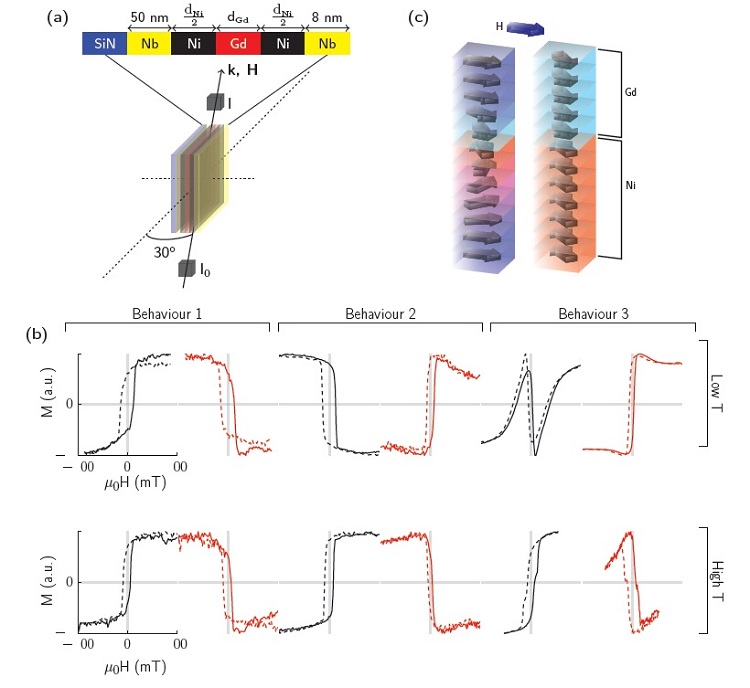

After measuring the magnetic response of the Ni and Gd individually, a model was constructed to find out the configuration of each atom’s magnetic moment and how the competition is resolved. Some results of the model and the experiment are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1(a) shows the geometry of the experimental setup. Figure 1(b) shows three different behaviors that were observed in samples with different thicknesses. The thinnest shows the same behavior at low and high temperatures with the Ni layers determining the orientation of the Gd layers (the Ni magnetization is positive at positive applied field values), which changes to the opposite in behavior 2 when the Gd thickness is increased.

The third behavior is from a sample within the range of layer thicknesses wherein the competing energies lead to a very interesting magnetic moment configuration. The model can tell exactly what this magnetic moment configuration is, and this is shown in Figure 1(c). On the left is a Gd/Ni interface in a high magnetic field with both Ni and Gd moments that are far from the interface aligning with the applied field direction, while there is significant twisting of the moments the closer they are to the interface. On the right, the system is shown at a very small value of applied field where the Gd moments are mainly pointing in the direction of the magnetic field with the Ni moments pointing in the opposite direction, but the effect of the small field is still strong enough to mean that the Ni still prevents the Gd from aligning with the field completely.

This pronounced change in the magnetic structure of a sample with small changes in applied magnetic field is important for any field of study in which the flow of a current through a structure can be modified by the magnetic state of the structure, for example spintronics or superconducting spintronics. In the context of superconducting spintronics it is possible to imagine a device which allows a resistanceless supercurrent to flow in one configuration, and prevents it in another. Effects such as this (the modification of flowing currents by an outside control) are of paramount importance in a technologically loaded world.

[1] M. N. Baibich et al., "Giant Magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr Magnetic Superlattices", Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2471 (1988)

[2] G. Binasch, P. Grünberg, F. Saurenbach and W. Zinn, "Enhanced Magnetoresistance in Layered Magnetic Structures with Antiferromagnetic Interlayer Exchange", Phys. Rev. B 39, 4828 (1989)

T. D. C. Higgs, S. Bonetti, H. Ohldag, N. Banerjee, X. L. Wang, A. J. Rosenberg, Z. Cai, J. H. Zhao, K. A. Moler and J. W. A. Robinson, "Magnetic Coupling at Rare Earth Ferromagnet/Transition Metal Ferromagnet Interfaces: A Comprehensive Study of Gd/Ni", Sci. Rep. 6, 30092 (16), DOI: 10.1038/srep30092.