by I. J. Pickering and G. N. George

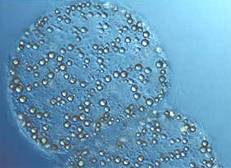

Sulfur is essential for all life, but it plays a particularly central role in the metabolism of many anaerobic microorganisms. Prominent among these are the sulfide-oxidizing bacteria that oxidize sulfide (S2-) to sulfate (SO42-). Many of these organisms can store elemental sulfur (S0) in "globules" for use when food is in short supply (Fig. 1). The chemical nature of the sulfur in these globules has been an enigma since they were first described as far back as 1887 (1); all known forms (or allotropes) of elemental sulfur are solid at room temperature, but globule sulfur has been described as "liquid", and it apparently has a low density – 1.3 compared to 2.1 for the common yellow allotrope a-sulfur. Various exotic forms of sulfur have been proposed to explain these properties, including micelles (small bubble-like structures) formed from long-chain polythionates, but all of these deductions have been based upon indirect evidence (for example the density was estimated by flotation of intact cells), and many questions remained.

Using X-ray absorption spectroscopy at the sulfur K-edge recorded on SSRL's Beam Line 6-2, Ingrid Pickering, Graham George and Eileen Yu (SSRL) together with co-workers from Arizona State University, University of British Columbia, and ExxonMobil Research and Engineering Co. (2) have resolved this long-standing conundrum.

|

| Figure 1: Optical micrograph of the giant bacterium Thiomargarita clearly showing sulfur globules as the small approximately spherical structures within the cell. This organism has particularly large cells (ca. ¾ mm), with correspondingly large (and more numerous) sulfur globules, which makes them easy to observe microscopically. |

|

| Figure 2: Sulfur K near-edge spectra from globules extracted from the bacterium Allochromatium vinosum in late logarithmic phase growth (points) in comparison with spectra of a-S8, S8 dissolved in xylene, and allyl polysulfides. The a-S8 spectrum is shown both undistorted (dashed line), and as calculated for 0.65 mm radius spheres (with density of 2.069 g.cm-3) measured in fluorescence, which gave the best fit to the experimental data. The inset shows a log plot of the residual as a function of the logarithm of the calculated radius (r), and exhibits a well-defined minimum at –0.19, equivalent to a globule radius of 0.65 m m. |

Measurements were made of cultures of seven quite different (taxonomically distinct) bacteria under various growth conditions. For all globule-containing cultures, the spectra contained a dominant component (globule sulfur) that strongly resembled the spectrum expected for a-sulfur. The structure of a-sulfur contains S8 crowns (Fig. 3), as do several other forms (e.g. the b- and g-sulfur allotropes). Large-scale crystallites of a -sulfur (or other forms) can be excluded from previous X-ray diffraction results (4), and Pickering and co-workers proposed that the globules consist of a core of fragments with local structures resembling a-sulfur, with a modified globule surface conferring hydrophilic (water-attracting properties (2). This might be due to the proteins that are known to be associated with the globules, or modification of surface sulfur by incorporation of polar groups such as thionates (5). In either case, the surface sulfur content must constitute such a small fraction of the total that it is unobservable by X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Rather than any of the exotic or novel forms of sulfur that have been proposed, bacteria appear to use sulfur in a form resembling the S8 crowns of the chemically least surprising and thermodynamically favored a-allotrope.

|

| Figure 3: The structure of well-known S8 crown found in a-sulfur (top) together with the structure of a long-chain polythionate molecule (bottom), both of which have been proposed to be present in bacterial sulfur globules. |

References:

- Winogradsky, S. Botanische Zeitung 1887, 31, 490-507.

- Pickering, I. J.; George, G. N.; Yu, E. Y.; Brune, D. C.; Tuschak, C.; Overmann, J.; Beatty, J. T.; Prince, R. C. Biochemistry, 2001, 40, 8138-8145.

- Pickering, I. J.; Prince, R. C.; Divers, T.; George, G.N. FEBS Lett. 1998, 441, 11-14.

- Hageage, G. J., Jr.; Eanes, E. D.; Gherna, R. L. J. Bacteriol. 1970, 101, 464-469.

- Steudel, R. In: Autotrophic Bacteria; Schlegel, H. G., Bothwien, B., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1989; pp. 289-303.

SSRL Highlights Archive